I am still not down on this program, though I sometimes don't know what I am hoping to achieve by recording the various stages of the journey, especially when, as is often the case, I don't have anything particular to say about the experience, let alone about the books themselves. The status of this old literature as a legitimate resource for serious mental engagement and development seems to be declining precipitously by the day in many quarters, and in those where it is still held in some regard among intelligent people I have not had much success ingratiating myself. However, I have to tell myself that even those people who appear to me to be more solidly embedded in these attractive social circles, are almost certainly lamenting that they are themselves lacking the truly dynamic friendships, lively conversations, and dangerous sexual frissons that fill the pages of the best loved books, however tantalizing some of their interactions with like-spirited peers either in real life or online may sometimes be. Indeed, if anyone even tangentially connected to the literary world is having any of the kind of raucous, invigorating social life that has at times in the past been associated with such artistic milieus, their public is not generally aware of it (and I would think if they were they, or their publishers, should want to publicize it, as it would undoubtedly improve their sales).

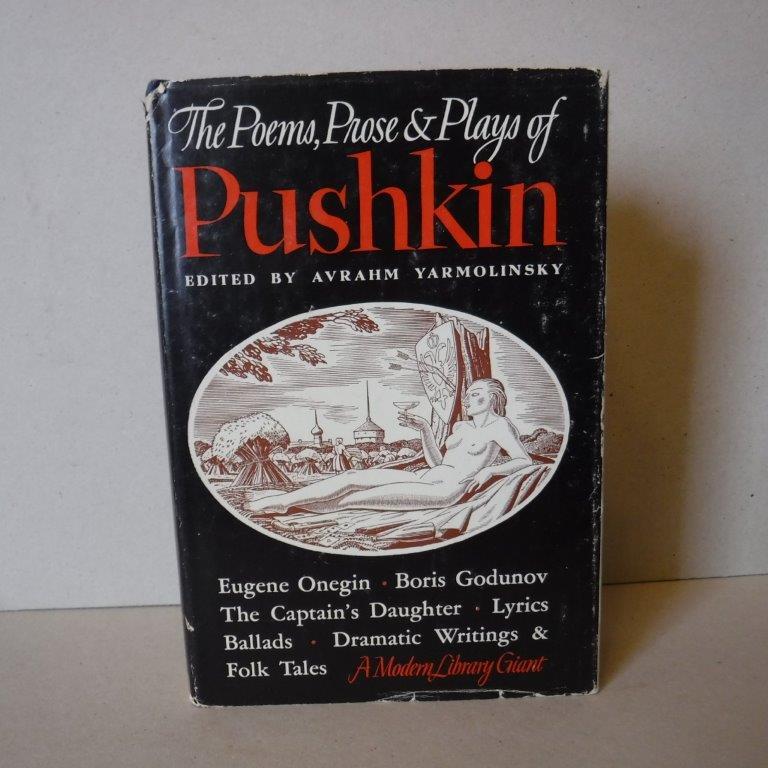

So this brings me to the circumstance of my being, at age fifty, for the first time reading, or even owning a book by the great Pushkin, one of the true all around literary threats of all time: he has three works on the IWE list, one play, albeit a kind of poem-play, one long poem, and one novella, in addition to being in general the acknowledged father of nineteenth century Russian literature. I don't know if there is another 19th century literary figure of this stature of whom I haven't read anything at all yet--maybe Goethe, though his most celebrated works were written in the late 1700s, I believe. Boris Godunov, as referenced above, is nominally a play, though written in verse, and no attempt was made to stage it until fifty years after it was written, when Pushkin had been long dead, and this was not a success, though the work was eventually of course the basis of a famous opera by Moussorgsky (I've tried to watch this opera on several occasions, but I have to confess I find it rather heavy going). From the IWE introduction: "When Pushkin wrote Boris Godunov in 1825 he was living under police surveillance, suspected of atheism. Pushkin is called the Russian Byron (because he was a contemporary of Byron's, was of similarly aristocratic birth, had similar poetic talent, and died similarly untimely) and he was influenced by Byron,but in this 'dramatic poem' he was influenced chiefly by Shakespeare. Boris is based on events of the years 1598-1605 and is semi-historical." Pushkin is known for having been part black. It is noted in the introduction to the 1936 Modern Library edition of his works that Pushkin's great-grandfather was "the Negro of Peter the Great, Ibrahim Hannibal, who seems to have been the son of an Ethiopian princeling." The writer of this introduction, one Ivrahm Yarmolinsky, noted that "The poet...liked to refer to his African origin, on one occasion speaking with sympathy of the fate of those he called 'my brother Negroes.'" Some might imagine this to be terribly cringe-inducing, but Pushkin was a pretty cool and dynamic guy and may well have been able to pull an attitude like this off. He wasn't one of those stiff German or Victorian English writers. Yarmolinsky goes on to add, "Whether or not this exotic strain in his heredity had anything to do with his sensual temperament and his keen feeling for rhythm must remain a matter of conjecture." The general European male deficiency in rhythm was apparently already a recognized phenomenon even in early 19th century Russia.

As literature goes, I find Pushkin to partake of most of the more admirable qualities of the Russian greats, the language so straightforward in its impact, weighty without being obscure (the translation, by the way, by Alfred Hayes, is very good, well-presented, etc.) I noted some other classic trait in him, but I cannot read my handwriting now to remember what it was. If this particular effort has a weakness, I would say it is in character development. Neither Boris Godunov nor his antagonist Dimitry the Pretender are particularly strongly drawn in ways that would seem to correlate with their roles, and Godunov's death, presumably by poisoning, though in the story he just all of a sudden gets sick and dies, was decidedly anticlimactic. The most vividly drawn character was Maryna the ambitious and cripplingly beautiful Polish princess and love interest of Dimitry who essentially tells him when he babbles about his love for her, "send for me when you are sitting on the throne". Other critics have found the plot to be too choppy, with constant jumps to new scenes and characters who appear only briefly, but I did not find this distracting, I thought it was fine.

All right, now, for some sample passages. From the cell in the Chudov Monastery, the aged to the younger monk, and later pretender and eventual czar of Russia:

"Complain not, brother, that the sinful world/Thou early didst forsake, that few temptations/ The All-High sent to thee. Believe my words;/The glory of the world, its luxury/Woman's seductive love, seen from afar,/Enslave our souls. Long have I lived, have taken/Delight in many things, but never knew/True bliss until that season when the Lord/Guided me to the cloister."

Men who have experienced pleasures can denounce those pleasures to their fellow men of the world, and men inexperienced in sensual life can debate the virtues of continuing to forgo these experiences among themselves, but there is always something grating when the man who has immersed himself in such activities on any kind of scale assures the man to whom these are inaccessible that he is not missing anything and is better off in his sheltered innocence, even though it be true.

My copy of the book is a castoff, in library binding, from Wellesley College. The check-out card is still in its sleeve calling out across the ages the names of the (imagined) beauties who took it out on loan from 1983 until its final borrowing in May of 1999, which years roughly correspond with my own era. Martha and Alice and Jessica and Wendy and Sheila and Michele and, last of all, Carla, after which Wellesley College, as far as we know, knew not Pushkin anymore.

From the Palace of the Czar, a charming little poetic disquisition on the young czarevitch's study of maps:

"Very good! Here's the sweet fruit/Of learning. One can view as from the clouds/Our whole dominion at a glance; its frontiers,/Its towns, its rivers. Study, son; 'tis science/That teaches us more swiftly than experience,/Our life being so brief. Some day, and soon/Perchance, the lands which thou so cunningly/To-day hast drawn on paper, all will come/Under thy hand."

Pushkin is good, but I wonder whether if he were not the "father" of the other 19th century Russian greats, he would have generated enough attention on his own to penetrate the Western European consciousness and been more or less included in the "canon". He is like an athlete who gets elected to his sport's Hall of Fame on the basis of having been a stalwart player on a great team, great enough that perhaps the team doesn't win a couple of its championships without his contributions, but about whom there has always been speculation as to how great he would have been in different circumstances. I then wrote some thoughts about my perception on how canons, or at least the Western canon, works, and why it isn't quite so easy for activist scholars or rabble rousers on Twitter to demand that some heretofore neglected person should immediately be considered the equal of Pushkin or whomever, but I want to refine them some before I go more into that.

In Cracow--Russian defectors to the Pretender:

"...we have fled from Moscow,/Disgraced, to thee our czar, and for thy sake/Are ready to lay down our lives; our corpses/Shall be for thee the steps to the royal throne."

A grim image. And for a pretender!

We get to Maryna, my favorite character. Her maid is speaking as she dresses the princess:

"They say that at the ball your gracious highness/Shone like the sun; men sighed, fair ladies whispered--/'Twas then that for the first time young Chodkiewicz/Beheld you, he who later shot himself."

No further context is given in the printed text.

Humorous scene where Maryna shuts down Dimitry's love talk. "I give my hand to the prince."

"I called myself Dimitry, and deceived the brainless Poles."

This is an affecting depiction of blindness:

"In my young days/...I lost my sight, and thenceforth knew not/Nor day, nor night, till my old age; in vain/...The Lord vouchsafed not/Healing to me.Then I lost hope at last,/And grew accustomed to my darkness. Even/Slumber showed not to me things visible,/Only of sounds I dreamed." At the time this made me ponder on the discomfort of waking and opening one's eyes without seeing anything, though I am not sure what exactly called up such sensations now.

As the play ends with Boris Godunov, his wife, and his son dead, and the rabble of Moscow exclaiming "Long live Czar Dimitry", I had the idea that one often gets from Shakespeare and the Greeks and other classic tragedies that with the end of the play the great crisis of the nation is over, the tumultuous personalities have burned themselves out and a more stable, if rather boring, leader has ascended the throne for a considerably less eventful reign. So I was surprised in looking into the history on which this play was based, about which I knew very little (this was during the period described in one book I used to own as when Russia "was about as well-known in England as the Iroquois nation"), that Dimitry only reigned for about 11 months, and was married to Maryna for just ten days before he was overthrown and executed in turn. Maryna was spared at this time, though later she would marry another false Dimitry (there was even a third one later on), whom she supposedly claimed to have recognized as her husband. False Dimitry II was killed before he was able to take the throne, and Maryna herself died in prison. Pushkin evidently had some plans to write further plays about these events, but was prevented from doing so by his early death at age 37.

Being me, naturally my thought on all this was, boy, that was going to a lot of trouble, walking all the way to Poland, carrying out an elaborate deception, raising an army and fighting one's way back across Russia, all to occupy the throne for a mere 11 months, and then getting ignominiously murdered by my own enemies. But a great spirit would think it was completely worth it, what after all is the purpose of life but to attempt great enterprises, woo the choicest women, etc. I am guessing that Pushkin's works in general adhere to this spirit in both their subject matter and boldness of expression.

Ever since finishing Bleak House (which was going to be my big quarantine book), in what, April? it has been a run through the spring and summer of much shorter books for this list. I am finally coming to one that is a little longer now, not Bleak House-sized, but it will probably take me a month to read it and get a report up. I've got about six or seven weeks left of reading outside for this year, and the autumn weather with the changing leaves, etc, will be on us probably in two weeks, which is perhaps the pleasantest but all too short-lived time of the year here.

The Bourgeois Surrender Challenge

This book produced a lot of weird search words specific to itself, so we got a weird tournament. While all of the movies and TV shows water down the tournament, they managed to prevent about ten obscure books about Russian studies with very long titles, multiple authors, etc, which had zero points from qualifying and making for an even lengthier tournament.

1. House: Season 1 Episode 8 (TV show)...............................................................................1,344

2. Craig Johnson--Death Without Company............................................................................1,183

3. House: Season 2 Episode 15 (TV show)................................................................................828

4. Louis L'Amour--The Walking Drum.......................................................................................716

5. Victoria and Albert (movie--2001).........................................................................................271

6. 1612 (movie--2007)................................................................................................................148

7. Frontier House (TV show-2002)............................................................................................130

8. Lisa Van Allen--The Night Garden.........................................................................................129

9. Pierre Gilliard--Thirteen Years at the Russian Court................................................................77

10. Sydney Tyler--The Japan-Russia War.....................................................................................24

11. Paul Watkins--The Ice Soldier.................................................................................................19

12. Michael Kort--A Brief History of Russia................................................................................16

13. T. J. Binyon--Pushkin: A Biography........................................................................................14

14. Hugo Vickers--The Crown Dissected (Seasons 1, 2, and 3)....................................................11

15. Benjamin Levin--This Crown is Mine......................................................................................11

16. In the Night Garden (TV Show)................................................................................................4

1st Round

#1 House over #16 In the Night Garden

TV shows automatically lose unless of course they draw another TV show. In the Night Garden is a British children's show that doesn't look particularly interesting even by the standards of a guy who has been watching children's TV shows for going on 20 years.

#2 Johnson over #15 Levin

Levin probably should have won, but given the backlog of books for this list that I already have to read, I don't that I am up for a 600 page tome on 17th century Russia.

#14 Vickers over #3 House

#4 L'Amour over #13 Binyon

Maybe some day I will take up reading 760 page literary biographies, but not right now.

#12 Kort over #5 Victoria and Albert

#11 Watkins over #6 1612

#10 Tyler over #7 Frontier House

#8 Van Allen over #9 Gilliard

This one probably would have gone to Gilliard, but this is an upset game.

2nd Round

#14 Vickers over #1 House

#12 Kort over #2 Johnson

The "brief" in the Brief History of Russia is the key here.

#4 L'Amour over #11 Watkins

This was a close game. L'Amour gets the edge for being the more recognized name. That is life. I suffer from it in the great blogging and social media competitions myself.

#8 Van Allen over #10 Tyler

Tyler is old (contemporaneous with the war itself) and long.

Final Four

#4 L'Amour over #14 Vickers

Vickers, who defeated 2 episodes of a single TV show to reach the Final Four, is about a TV show that I haven't seen.

#12 Kort over #8 Van Allen

Reviews of Lily Van Allen often compare her to Alice Hoffman, a former champion here, whose book, however, I could not get through when I tried to read it.

Championship

#4 L'Amour over #12 Kort

I was not hugely excited about any of the books in this tournament. L'Amour was pretty much the favorite to win because he had a couple of upsets to use, but it wasn't like there was any obvious occasion to use them. And the guy did after all sell 500 million books or something in the days when people actually did read, so there must be some entertainment value in them.

No comments:

Post a Comment