A List: Shakespeare--Richard II............................................................5/32

B List: Trollope--Barsetshire Chronicles: Barchester Towers.......597/746

C List: Bill Bryson--I'm a Stranger Here Myself..............................14/288

Richard II is the 3rd of a run of Shakespeare plays--the other 2 being Henry VI Part 1 and Troilus and Cressida--that had not managed to come up on the A list yet. I have recorded somewhere how many of the Shakespeare plays I have read at one time or another--some of the lesser known ones that I have only read once I have trouble remembering whether I have or not--but I got very busy this week, one of my cars had to go into the shop, etc, so I didn't get around to looking up how many of them I have marked down. I think around 2/3rds of the 37, or is it 38? As with most things, even great ones, I have periods in my life where the greatness of Shakespeare reveals itself more readily and is more important to my daily life and the firing of my imaginative faculties than it is at other times. I am not in one of those special times currently. I hope I have a couple more such epochs left in me.

I am probably in close to the ideal frame of mind for taking on Trollope, but I will expand on this in the big essay that I'll do when I finish the book.

Obviously I have just started the Bryson book, which was published in 1999 and seems to be a series of humorous vignettes around his return to the United States (actually Hanover, New Hampshire, which is a fine town but about as unrepresentative of the real United States as you can get) after 20 years abroad. Some of my impressions 14 pages in are as follows:

1. Though the book is less than 20 years old the world depicted in it is so dated as to be almost comical. We've already been treated to five pages on the wonders of the postal service, and a letter from England that made it to his house despite being addressed merely "New Hampshire, somewhere in America". Then there was a reminiscence about coming home from the pub in England and watching 90 minute science programs on television before going to bed. Basically this looks like it is going to be chock full of activities, jobs, cultural habits, that died within about five years of this book's publication.

2. It is unbelievable that within living memory--heck, my own early adulthood--people could apparently make upper middle class incomes writing, well, I don't know, stuff like what I've just described, and have fabulous overall careers. This guy Bryson in his heyday sold voluminous numbers of books (5.9 million in the 2000s alone!), made many TV appearances, gave lecture tours, was the chancellor of Durham University. I know people will say a person like me has no idea how difficult it is to be a professional writer who has to turn out regular work on a deadline and how serious this is and all right, fine. Even so, this guy has to get up every day and think, whew, I lucked out in the timing of my career. But maybe he doesn't.

3. I feel like this "I left America for x number of years and boy did things change a lot" theme was a popular one in the late 90s that has kind of gone away. Does anybody at the educated level of society really leave anywhere and not return for years on end anymore? Is it really possible to "get away" the way it used to be in the modern overconnected world?

...I too am on a deadline for this one monthly post and my time is up now.

This guy will not be stopped.

Thursday, December 6, 2018

Wednesday, November 7, 2018

November 2018

A List: James Russell Lowell--A Fable For Critics..........................................66/95

B List: Anthony Trollope--Barsetshire Chronicles (Barchester Towers)......273/746

C List: Lucy Lethbridge--Servants: A Downstairs View of 20th Cent, etc....216/325

The weather turned chilly early this year. My last real day of reading on the porch was October 10th, when it was 80 degrees. The next day it dropped down to the low 60s and poured rain. I tried to go out but gave it up after about 10 minutes and came back in. After that it dropped into the lower 50s and 40s and has stayed there ever since. I'll probably be inside now until May.

The James Russell Lowell work here is a bit of 19th century doggerel verse that I am reading online, because even the state library doesn't have a printed copy of it that circulates. It is something of a humorous overview of the American--really the New England literary and cultural scene, with a few New Yorkers such as Cooper included, circa 1850. I am reading it because some of the lines on Emerson were excerpted for one of the exam questions in the GRE book I get this list from.

Barchester Towers is the second volume of the Barsetshire Chronicles. I have already dusted off The Warden, which clocks in at a trim 199 pages. There are six novels in the series altogether, but the IWE list only features and summarizes the first two. These first two novels were also published together in a single Modern Library edition, with no accompanying books containing any of the other four. So I think I am only going to read the first two as well, especially seeing as these make for a long enough book anyway. They are very good though. I find myself often regretting that I have to stop for the day and can't go on because I want to see what happens next, which is something that rarely occurs with me anymore, even when I generally like what I'm reading. But this is my first time ever reading Trollope, so he is both new to me and the kind of writer I am inclined to like, which I guess is a combination I don't encounter that often anymore.

The Lucy Lethbridge book, a survey of the British servant experience and the decline of that way of life over the past century, feels a little padded at times but contains some matters of interest to me. I always like it when the time for some activity or social arrangement has passed, but there are still people trying to carry on the old forms onto the point of ridiculousness, such as the dowager in the late 1930s who requires a staff of 8 people to pull together a glass of Benger's (Ovaltine-like drink) and two slices of toast and bring it to her room on a silver tray. I had not been aware that many of the great country houses of England did not get electricity or in some cases even modern bathrooms until well into the 30s (the chamberpot long remained the outlet of choice, it seems). I also had not known about the extreme preference for height when footmen, serving maids and other visible help. There was one lord who required all the women on his staff to be at least five foot ten, and he employed around thirty of them. I would not have thought there would be so much height to go around.

The author, Lucy Lethbridge, indicates in the dedication that one of her grandmothers at least was in service. I've been digging around the internet for pictures of her when she was younger, even at age 40. The only ones I can find are from when her book came out, at which time she was around fifty, but she gives one the idea that she was probably a looker, to somebody like me anyway, in her younger years. The combination of lingering working class earthy sensuality with such evidences of a decent education as can be presumed would decidedly hit my sweet spots. But I suppose we'll never know.

Near the head of my long, long list of romantic regrets is never having had any kind of relations with a real English girl. I mean even a few words over a drink. I don't know that I've ever even talked to one. That's how elusive they are to the likes of me.

This is the actress who plays one of the Stanhope daughters in the BBC Adaptation of 'Barchester Towers'. I just left off today at the chapter where the Reverend Stanhope was recalled to his parish by the new bishop after spending 13 years in Italy so I have not encountered these characters yet. Apparently their role is not a minor one.

B List: Anthony Trollope--Barsetshire Chronicles (Barchester Towers)......273/746

C List: Lucy Lethbridge--Servants: A Downstairs View of 20th Cent, etc....216/325

The weather turned chilly early this year. My last real day of reading on the porch was October 10th, when it was 80 degrees. The next day it dropped down to the low 60s and poured rain. I tried to go out but gave it up after about 10 minutes and came back in. After that it dropped into the lower 50s and 40s and has stayed there ever since. I'll probably be inside now until May.

The James Russell Lowell work here is a bit of 19th century doggerel verse that I am reading online, because even the state library doesn't have a printed copy of it that circulates. It is something of a humorous overview of the American--really the New England literary and cultural scene, with a few New Yorkers such as Cooper included, circa 1850. I am reading it because some of the lines on Emerson were excerpted for one of the exam questions in the GRE book I get this list from.

Barchester Towers is the second volume of the Barsetshire Chronicles. I have already dusted off The Warden, which clocks in at a trim 199 pages. There are six novels in the series altogether, but the IWE list only features and summarizes the first two. These first two novels were also published together in a single Modern Library edition, with no accompanying books containing any of the other four. So I think I am only going to read the first two as well, especially seeing as these make for a long enough book anyway. They are very good though. I find myself often regretting that I have to stop for the day and can't go on because I want to see what happens next, which is something that rarely occurs with me anymore, even when I generally like what I'm reading. But this is my first time ever reading Trollope, so he is both new to me and the kind of writer I am inclined to like, which I guess is a combination I don't encounter that often anymore.

The Lucy Lethbridge book, a survey of the British servant experience and the decline of that way of life over the past century, feels a little padded at times but contains some matters of interest to me. I always like it when the time for some activity or social arrangement has passed, but there are still people trying to carry on the old forms onto the point of ridiculousness, such as the dowager in the late 1930s who requires a staff of 8 people to pull together a glass of Benger's (Ovaltine-like drink) and two slices of toast and bring it to her room on a silver tray. I had not been aware that many of the great country houses of England did not get electricity or in some cases even modern bathrooms until well into the 30s (the chamberpot long remained the outlet of choice, it seems). I also had not known about the extreme preference for height when footmen, serving maids and other visible help. There was one lord who required all the women on his staff to be at least five foot ten, and he employed around thirty of them. I would not have thought there would be so much height to go around.

The author, Lucy Lethbridge, indicates in the dedication that one of her grandmothers at least was in service. I've been digging around the internet for pictures of her when she was younger, even at age 40. The only ones I can find are from when her book came out, at which time she was around fifty, but she gives one the idea that she was probably a looker, to somebody like me anyway, in her younger years. The combination of lingering working class earthy sensuality with such evidences of a decent education as can be presumed would decidedly hit my sweet spots. But I suppose we'll never know.

Near the head of my long, long list of romantic regrets is never having had any kind of relations with a real English girl. I mean even a few words over a drink. I don't know that I've ever even talked to one. That's how elusive they are to the likes of me.

This is the actress who plays one of the Stanhope daughters in the BBC Adaptation of 'Barchester Towers'. I just left off today at the chapter where the Reverend Stanhope was recalled to his parish by the new bishop after spending 13 years in Italy so I have not encountered these characters yet. Apparently their role is not a minor one.

Monday, October 15, 2018

Ellen Glasgow--Barren Ground (1925)

"Ellen Glasgow's reputation" says the IWE introduction, "was already good and her novels many, but the publication of Barren Ground in 1926 (?) was what chiefly made it clear that she was a major novelist. Mrs Glasgow wrote not about her own upper-class circles--though later she proved she could do so with equal success--but about the rural people of the countryside near her native Richmond, Virginia. Like fine poetry or music Barren Ground in its writing reflects the temperament of the action depicted, dull or emotional or brisk as the case may be." The "Note on the Author" in the circa 1936 Modern Library edition I had is somewhat more pointed and colorful:

"The proud South at first resented and then acclaimed one of its aristocratic daughters for her revolt against the sentimental tradition of her environment. Born in Richmond, Virginia, Ellen Glasgow had all the advantages of education and leisure of the privileged. After taking her degree and winning a Phi Beta Kappa key at the University of Virginia, Miss Glasgow began her career as an author with the publication of an anonymous novel in 1897. In open defiance of the genteel prejudice against women expressing themselves on such controversial subjects as politics, Miss Glasgow staked her reputation and social position on a novel published under her own name. The Voice of the People was an instantaneous success. Since its appearance one novel has followed another and Miss Glasgow's reputation has grown steadily. Today she ranks as one of the leading women novelists of the country..."

I don't know why the IWE refers to her as "Mrs" while the Modern Library uses "Miss".

Taking into consideration her former status, what I perceive to be the general desire for female writers of the past to be more appreciated, and the circumstance that Barren Ground at least is a book of considerable literary quality that even apart from having a quite empowered heroine for its time offers much of value to the national literary landscape, it is perhaps surprising that Ellen Glasgow is not more remembered. I suspect her handling of race, while not overtly mean-spirited or to me obtrusively offensive given her generation and the atmosphere in which she lived, is not adequate to the requirements of our era. Her overall attitude in this area struck me as having some similarity to Faulkner's (which I hear criticized as well), but of course without his subtlety and force to mitigate some of the more obvious objections to be made. This subject will inevitably come up several times during this report.

Remarkably, I cannot recall ever having read a novel set in Virginia before this, which especially stands out to me because I have lived in that state (though it is my least favorite place that I have lived). I suppose I have read some D.C.-set books where one of the characters lived in Arlington or worked at the Pentagon or a Civil War book where some of the camp or battle scenes took place there, but this is the first I can think of with a domestic setting, extensive description of nature and seasons and local society over a period of many years and so forth. I took a lot of notes on it.

p.5 "...the greater number arrived, as they remained, 'good people,' a comprehensive term, which implies, to Virginians, the exact opposite of the phrase, 'a good family.' The good families of the state have preserved, among other things, custom, history, tradition, romantic fiction, and the Episcopal Church. The good people, according to the records of clergymen, which are the only surviving records, have preserved nothing except themselves."

(Early on) This book is part "The Waltons", part As the Earth Turns, with a hint of Faulkner.

Sexuality in old books is (generally speaking) normal. Conventional love affairs, etc, of a brief duration in which the intensity is even more vanishingly fleeting. Instances of women being highly promiscuous, incest, etc, are understood, or at least presumed, to be unusual. Less anxiety for bourgeois readers, which perhaps they need once in a while.

p.43 "Mrs Oakley looked down on the 'poor white' class, though she had married into it...He had made her a good husband; it was not his fault that he could never get on; everything from the start had been against him; and he had always done the best that he could." I hope my wife doesn't read this passage, lest some truths hit too close to home.

p. 81 "Until yesterday Dorinda had regarded the monotonous routine of the store as one of the dreary, though doubtless beneficial, designs of an inscrutable Providence." That "though doubtless beneficial" is a good piece of characterization.

The use of black dialect throughout here is probably such as to be offensive. Glasgow is not a comic writer, so she is going for realism, not humor. I have seen it done worse, but perhaps we don't need quite so much of it to make the point. On the other hand, is there no value in her having made some record of it? Assuming it is accurate. One presumes that she lived among people like these characters, and that their speech was distinct from that common among the whites, and also she was a conscientious writer of well above average literary skill, so "accuracy" insofar as she is presenting her own interpretation of what she heard, does not seem to me to be problematic and would certainly be in accord with literary custom.

Like many older books, this took around 100 pages to get going. My sense is that consensus opinion today holds that that is too long even for supposedly great books and demands way too much of a person's time to be worthwhile in the modern world. I would dispute that of course, because I like what I take to be the expansive effects of leisurely book-reading on my own mind mostly, though I don't think the trend of even smarter younger people moving away from this practice is really benefiting their cognitive development. Such knowledge as they acquire seems to me to be confined with narrower channels into which more reading perhaps would have allowed more air and a more comprehensive vision.

Old books have two main kinds of pregnancy dilemmas. Either the boy is too low status to avoid a forced marriage/have the problem taken care of, or he is too high status to be forced into marriage (from the girl's point of view). We have the second type of that sad story here.

p. 274 "She wished he wouldn't say 'ni**ers.' That scornful label was already archaic, except among the poorest of the 'poor white class' at Pedlar's Mill." This is somewhat progressive, I suppose, but then a few pages later (281-2) there is the somewhat ubiquitous white author denial/avoidance/whitewashing passage that has become mostly inexcusable in our days:

"Like her mother, she was endowed with an intuitive understanding of the negroes; she would always know how to keep on friendly terms with that immature but not ungenerous race. Slavery in Queen Elizabeth County had rested more lightly than elsewhere...It was true that the coloured people about Pedlar's Mill were as industrious and as prosperous as any in the South, and that, within what their white neighbours called reasonable bounds, there was, at the end of the nineteenth century, little prejudice against them...As for the negroes themselves, they lived contentedly enough as inferiors though not dependents."

My copy, alas, did not have this groovy dust jacket.

p. 324 "Mrs. Oakley was a pious and God-fearing woman, whose daily life was lived beneath the ominous shadow of the wrath to come; yet she had deliberately perjured herself in order that a worthless boy might escape the punishment which she knew he deserved." It is my observation that women authors are much more likely, if not to directly refer to certain male characters in such withering terms as "worthless", "inferior", "cowardly", etc, to develop them at greater length and detail before passing down these oracular judgments, which I find gives them a certain sting whose impression lasts longer than the introduction of such characters in male authors, whose purpose more frequently is merely to give the hero someone to defeat or otherwise display his own overwhelming superiority in contrast with, and whose existence or behavior is otherwise of little significance.

p. 326 "The Lord helps good sleepers." I hope so.

p. 365 "She had seen enough of the world to know that you took your husband...where you found him, and she was troubled by few illusions about marriage."

p. 371 "That, she had learned, was the hidden sting of success; it rubbed old sores with the salt of regret until they were raw again."

p. 372 "Yes, that's the trouble about getting comforts. We always remember that other people went without them. I've got the carpets now that Rose Emily wanted." I like this last quote, there seems to me to be something in it. The two previous I am not as convinced of, but in the context of the book I thought what it revealed about its character's point of view was interesting.

p. 443 "It had never seemed possible to her that Nathan could die. He had not mattered enough for that." This is the main character's husband, whom she married at a rather mature age, 38 or so. It is implied in the book that sexual consummation in this marriage was never achieved. The character, Dorinda, had given herself to a lover at age 20 and been jilted, and the plot of the book is essentially the long grind through the rest of her life to renounce passion and love overcome this setback and the exhausted, narrow life of her rural community to become successful and gain a measure of revenge on her onetime lover, who eventually descends into alcoholism and poverty. This aspect of a woman who determines to get along without dependence on or emotional connection to males or to be weighed down by children was actually rather timely given the recent outpouring of female anger and disgust with much of masculine society that has become so prominent in the culture.

p. 511 "I've seen so many people die," she thought, and then, "In fifty years many people must die." I only note this because this is the point of life that I am at now.

p. 521 "Youth can never know the worst, she understood, because the worst that one can know is the end of expectancy."

Dorinda's struggle with love, both getting over the jilting of her early life and her refusal to engage with it at all in the remainder of the book, I thought was too much. Several times the reader is assured that she has overcome any bitterness or desire for it that she may have had once and for all, but the supposedly suppressed feelings seem to be aroused too easily and too often for this to be wholly credible.

The Bourgeois Surrender Challenge

1. Toni Morrison--The Bluest Eye......................................................1,234

2. William James--The Varieties of Religious Experience....................311

3. Taxi (movie--2004)............................................................................289

4. Winston Graham--Poldark: The Black Moon....................................279

5. D. C. Cab (movie)..............................................................................165

6. Eric Weiner--The Geography of Genius............................................158

7. A.P.J. Abdul Kalam--Wings of Fire..................................................114

8. J.L. Langley--The Tin Star.................................................................109

9. Nathaniel Hawthorne--The Blithedale Romance.................................58

10. Rebecca Morris--A Murder in My Hometown...................................38

11. The Thundermans: Adventures in Supersitting (Vol. 1, Ep. 1)(TV)..30

12. Dara Berger--How to Prevent Autism................................................26

13. 1,001 Wines You Must Try Before You Die (ed. Beckett)..................21

14. Taxicab Confessions (TV Series).........................................................6

15. Reynolds Price--Clear Pictures: First Loves, First Guides.................5

16. Marco Polo New York Guide...............................................................3

First Round

#1 Morrison over #16 Marco Polo New York

Not that I don't love travel guides.

#2 James over #15 Price

I don't know what is supposed to be going on with the Price book.

#14 Taxicab Confessions over #3 Taxi

One of the magic words that was used to call up contestants for this tournament was "cab". Taxicab Confessions, while I don't think it is supposed to be particularly good, sounds more interesting than Taxi, which is rated as dreadful despite the appearance of Gisele Bundchen, the wife of Tom Brady of Ted movies fame.

#4 Graham over #13 1,001 Wines

The Poldark books are evidently popular reading, and literarily respectable enough to get the BBC adaptation treatment. I believe my wife has seen the TV series.

#12 Berger over #5 D. C. Cab

This book sounds like a crock, but even that isn't enough to lose to a legendarily bad movie.

#6 Weiner over #11 The Thundermans

#10 Morris over #7 Kalam

Neither of these books is carried by a single library in my state, and neither of them has a title that excites me.

#9 Hawthorne over #8 Langley

Elite Eight

#1 Morrison over #14 Taxicab Confessions

#2 James over #12 Berger

#4 Graham over #10 Morris

#9 Hawthorne over #6 Weiner

This one was a decent contest following three routs.

Final Four

#1 Morrison over #9 Hawthorne

The game of the tournament. I figure it is time I read something by Toni Morrison, and her first book would seem to be a logical starting point for that.

#2 James over #4 Graham

I have mixed feelings about whether I would like the Poldark books or not. Maybe it could win in a different field.

Championship

#1 Morrison over #2 James

"The proud South at first resented and then acclaimed one of its aristocratic daughters for her revolt against the sentimental tradition of her environment. Born in Richmond, Virginia, Ellen Glasgow had all the advantages of education and leisure of the privileged. After taking her degree and winning a Phi Beta Kappa key at the University of Virginia, Miss Glasgow began her career as an author with the publication of an anonymous novel in 1897. In open defiance of the genteel prejudice against women expressing themselves on such controversial subjects as politics, Miss Glasgow staked her reputation and social position on a novel published under her own name. The Voice of the People was an instantaneous success. Since its appearance one novel has followed another and Miss Glasgow's reputation has grown steadily. Today she ranks as one of the leading women novelists of the country..."

I don't know why the IWE refers to her as "Mrs" while the Modern Library uses "Miss".

Taking into consideration her former status, what I perceive to be the general desire for female writers of the past to be more appreciated, and the circumstance that Barren Ground at least is a book of considerable literary quality that even apart from having a quite empowered heroine for its time offers much of value to the national literary landscape, it is perhaps surprising that Ellen Glasgow is not more remembered. I suspect her handling of race, while not overtly mean-spirited or to me obtrusively offensive given her generation and the atmosphere in which she lived, is not adequate to the requirements of our era. Her overall attitude in this area struck me as having some similarity to Faulkner's (which I hear criticized as well), but of course without his subtlety and force to mitigate some of the more obvious objections to be made. This subject will inevitably come up several times during this report.

Remarkably, I cannot recall ever having read a novel set in Virginia before this, which especially stands out to me because I have lived in that state (though it is my least favorite place that I have lived). I suppose I have read some D.C.-set books where one of the characters lived in Arlington or worked at the Pentagon or a Civil War book where some of the camp or battle scenes took place there, but this is the first I can think of with a domestic setting, extensive description of nature and seasons and local society over a period of many years and so forth. I took a lot of notes on it.

p.5 "...the greater number arrived, as they remained, 'good people,' a comprehensive term, which implies, to Virginians, the exact opposite of the phrase, 'a good family.' The good families of the state have preserved, among other things, custom, history, tradition, romantic fiction, and the Episcopal Church. The good people, according to the records of clergymen, which are the only surviving records, have preserved nothing except themselves."

(Early on) This book is part "The Waltons", part As the Earth Turns, with a hint of Faulkner.

Sexuality in old books is (generally speaking) normal. Conventional love affairs, etc, of a brief duration in which the intensity is even more vanishingly fleeting. Instances of women being highly promiscuous, incest, etc, are understood, or at least presumed, to be unusual. Less anxiety for bourgeois readers, which perhaps they need once in a while.

p.43 "Mrs Oakley looked down on the 'poor white' class, though she had married into it...He had made her a good husband; it was not his fault that he could never get on; everything from the start had been against him; and he had always done the best that he could." I hope my wife doesn't read this passage, lest some truths hit too close to home.

p. 81 "Until yesterday Dorinda had regarded the monotonous routine of the store as one of the dreary, though doubtless beneficial, designs of an inscrutable Providence." That "though doubtless beneficial" is a good piece of characterization.

The use of black dialect throughout here is probably such as to be offensive. Glasgow is not a comic writer, so she is going for realism, not humor. I have seen it done worse, but perhaps we don't need quite so much of it to make the point. On the other hand, is there no value in her having made some record of it? Assuming it is accurate. One presumes that she lived among people like these characters, and that their speech was distinct from that common among the whites, and also she was a conscientious writer of well above average literary skill, so "accuracy" insofar as she is presenting her own interpretation of what she heard, does not seem to me to be problematic and would certainly be in accord with literary custom.

Like many older books, this took around 100 pages to get going. My sense is that consensus opinion today holds that that is too long even for supposedly great books and demands way too much of a person's time to be worthwhile in the modern world. I would dispute that of course, because I like what I take to be the expansive effects of leisurely book-reading on my own mind mostly, though I don't think the trend of even smarter younger people moving away from this practice is really benefiting their cognitive development. Such knowledge as they acquire seems to me to be confined with narrower channels into which more reading perhaps would have allowed more air and a more comprehensive vision.

Old books have two main kinds of pregnancy dilemmas. Either the boy is too low status to avoid a forced marriage/have the problem taken care of, or he is too high status to be forced into marriage (from the girl's point of view). We have the second type of that sad story here.

p. 274 "She wished he wouldn't say 'ni**ers.' That scornful label was already archaic, except among the poorest of the 'poor white class' at Pedlar's Mill." This is somewhat progressive, I suppose, but then a few pages later (281-2) there is the somewhat ubiquitous white author denial/avoidance/whitewashing passage that has become mostly inexcusable in our days:

"Like her mother, she was endowed with an intuitive understanding of the negroes; she would always know how to keep on friendly terms with that immature but not ungenerous race. Slavery in Queen Elizabeth County had rested more lightly than elsewhere...It was true that the coloured people about Pedlar's Mill were as industrious and as prosperous as any in the South, and that, within what their white neighbours called reasonable bounds, there was, at the end of the nineteenth century, little prejudice against them...As for the negroes themselves, they lived contentedly enough as inferiors though not dependents."

My copy, alas, did not have this groovy dust jacket.

p. 324 "Mrs. Oakley was a pious and God-fearing woman, whose daily life was lived beneath the ominous shadow of the wrath to come; yet she had deliberately perjured herself in order that a worthless boy might escape the punishment which she knew he deserved." It is my observation that women authors are much more likely, if not to directly refer to certain male characters in such withering terms as "worthless", "inferior", "cowardly", etc, to develop them at greater length and detail before passing down these oracular judgments, which I find gives them a certain sting whose impression lasts longer than the introduction of such characters in male authors, whose purpose more frequently is merely to give the hero someone to defeat or otherwise display his own overwhelming superiority in contrast with, and whose existence or behavior is otherwise of little significance.

p. 326 "The Lord helps good sleepers." I hope so.

p. 365 "She had seen enough of the world to know that you took your husband...where you found him, and she was troubled by few illusions about marriage."

p. 371 "That, she had learned, was the hidden sting of success; it rubbed old sores with the salt of regret until they were raw again."

p. 372 "Yes, that's the trouble about getting comforts. We always remember that other people went without them. I've got the carpets now that Rose Emily wanted." I like this last quote, there seems to me to be something in it. The two previous I am not as convinced of, but in the context of the book I thought what it revealed about its character's point of view was interesting.

p. 443 "It had never seemed possible to her that Nathan could die. He had not mattered enough for that." This is the main character's husband, whom she married at a rather mature age, 38 or so. It is implied in the book that sexual consummation in this marriage was never achieved. The character, Dorinda, had given herself to a lover at age 20 and been jilted, and the plot of the book is essentially the long grind through the rest of her life to renounce passion and love overcome this setback and the exhausted, narrow life of her rural community to become successful and gain a measure of revenge on her onetime lover, who eventually descends into alcoholism and poverty. This aspect of a woman who determines to get along without dependence on or emotional connection to males or to be weighed down by children was actually rather timely given the recent outpouring of female anger and disgust with much of masculine society that has become so prominent in the culture.

p. 511 "I've seen so many people die," she thought, and then, "In fifty years many people must die." I only note this because this is the point of life that I am at now.

p. 521 "Youth can never know the worst, she understood, because the worst that one can know is the end of expectancy."

Dorinda's struggle with love, both getting over the jilting of her early life and her refusal to engage with it at all in the remainder of the book, I thought was too much. Several times the reader is assured that she has overcome any bitterness or desire for it that she may have had once and for all, but the supposedly suppressed feelings seem to be aroused too easily and too often for this to be wholly credible.

The Bourgeois Surrender Challenge

1. Toni Morrison--The Bluest Eye......................................................1,234

2. William James--The Varieties of Religious Experience....................311

3. Taxi (movie--2004)............................................................................289

4. Winston Graham--Poldark: The Black Moon....................................279

5. D. C. Cab (movie)..............................................................................165

6. Eric Weiner--The Geography of Genius............................................158

7. A.P.J. Abdul Kalam--Wings of Fire..................................................114

8. J.L. Langley--The Tin Star.................................................................109

9. Nathaniel Hawthorne--The Blithedale Romance.................................58

10. Rebecca Morris--A Murder in My Hometown...................................38

11. The Thundermans: Adventures in Supersitting (Vol. 1, Ep. 1)(TV)..30

12. Dara Berger--How to Prevent Autism................................................26

13. 1,001 Wines You Must Try Before You Die (ed. Beckett)..................21

14. Taxicab Confessions (TV Series).........................................................6

15. Reynolds Price--Clear Pictures: First Loves, First Guides.................5

16. Marco Polo New York Guide...............................................................3

First Round

#1 Morrison over #16 Marco Polo New York

Not that I don't love travel guides.

#2 James over #15 Price

I don't know what is supposed to be going on with the Price book.

#14 Taxicab Confessions over #3 Taxi

One of the magic words that was used to call up contestants for this tournament was "cab". Taxicab Confessions, while I don't think it is supposed to be particularly good, sounds more interesting than Taxi, which is rated as dreadful despite the appearance of Gisele Bundchen, the wife of Tom Brady of Ted movies fame.

#4 Graham over #13 1,001 Wines

The Poldark books are evidently popular reading, and literarily respectable enough to get the BBC adaptation treatment. I believe my wife has seen the TV series.

#12 Berger over #5 D. C. Cab

This book sounds like a crock, but even that isn't enough to lose to a legendarily bad movie.

#6 Weiner over #11 The Thundermans

#10 Morris over #7 Kalam

Neither of these books is carried by a single library in my state, and neither of them has a title that excites me.

#9 Hawthorne over #8 Langley

Elite Eight

#1 Morrison over #14 Taxicab Confessions

#2 James over #12 Berger

#4 Graham over #10 Morris

#9 Hawthorne over #6 Weiner

This one was a decent contest following three routs.

Final Four

#1 Morrison over #9 Hawthorne

The game of the tournament. I figure it is time I read something by Toni Morrison, and her first book would seem to be a logical starting point for that.

#2 James over #4 Graham

I have mixed feelings about whether I would like the Poldark books or not. Maybe it could win in a different field.

Championship

#1 Morrison over #2 James

Friday, October 5, 2018

(R)October 2018

A List--Nathaniel West--A Cool Million...................25/119

B List--Between books

C List--Between books

This month's check-in catches me on an off day. I am working on the report for B, and the book due up for C was a novel by Philip Pullman that was highly rated but I didn't realize it was a Harry Potteresque fantasy/young adult type book. I read about 20 pages of it and wasn't interested, so I'm waiting to get to the library to get the next title for that list.

Nathaniel West is, by some people anyway, a celebrated American satirist of the 1930s. I did read his most famous book, Miss Lonelyhearts, a few years back. It didn't make much of an impression on me. This one is supposed to be a spoof on the Horatio Alger genre. The first few pages were funny, then an orphan girl character got introduced who has already been the victim of two rapes, the first when she was twelve years old, and who works in the employ of a local lawyer and town who takes down her pants and spanks her twice a week. I get that this is supposed to be part of the dark skewering of banal conventions, and it does give the story some bite, or at least a sense of controversy, and I am attracted to that, but at the same time it is difficult in the current environment to react to its being presented in this rather light way in the spirit which is probably conducive to the way this episode is supposed to be understood. In general I am almost always ultimately disappointed by these kinds of books, even by their better practitioners such as Waugh. I am just not thoroughly (wickedly?) cynical enough by nature to derive the full enjoyment from them. Besides the likelihood that they don't seem to age very well, for them to work the humor and thrust have to be quite sophisticated, I find, and this is where Waugh is strong. One of the oddities of our time is that Donald Trump would seem to be such an obvious target for a devastating satire, and truly millions of people are offering would-be witty and devastating commentary on his entire persona on a daily basis, yet I cannot remember anything of the sort that I thought was particularly funny or clarifying about the absurd situation we find ourselves in, not that I have read everything, of course. Trump is a slippery target I suppose because he genuinely seems (along with his supporters) to regard his detestable qualities as in fact great strengths, and this detail seems to be beyond the comprehension of his critics, which dulls their ability to mock him. Instead, the most delicious targets for satire in the current environment are the Resistance and the virtue signalers who regard themselves with hilarious self-seriousness as moral paragons, at least compared to their cultural and political enemies, and the guardians of the true Republic. Not that the Trumpists are not delusional too I suppose but the attacks on them are so obvious and predictable, I guess, they don't have any sophisticated force beyond brute rage....

This is the time of year when I start to count down the days I have left to read on the porch before I have to close that up for the winter. Most years I feel like I can get out there most days up to October 20th or so, but this year even the second half of September has been chilly. I've only gotten out there a couple of days each week the past fortnight, as there have been a lot of days where the high temperature was 57 degrees (and raining). It looks like there are two or three days coming this week which will be warm enough to go outside, but that might be it...

B List--Between books

C List--Between books

This month's check-in catches me on an off day. I am working on the report for B, and the book due up for C was a novel by Philip Pullman that was highly rated but I didn't realize it was a Harry Potteresque fantasy/young adult type book. I read about 20 pages of it and wasn't interested, so I'm waiting to get to the library to get the next title for that list.

Nathaniel West is, by some people anyway, a celebrated American satirist of the 1930s. I did read his most famous book, Miss Lonelyhearts, a few years back. It didn't make much of an impression on me. This one is supposed to be a spoof on the Horatio Alger genre. The first few pages were funny, then an orphan girl character got introduced who has already been the victim of two rapes, the first when she was twelve years old, and who works in the employ of a local lawyer and town who takes down her pants and spanks her twice a week. I get that this is supposed to be part of the dark skewering of banal conventions, and it does give the story some bite, or at least a sense of controversy, and I am attracted to that, but at the same time it is difficult in the current environment to react to its being presented in this rather light way in the spirit which is probably conducive to the way this episode is supposed to be understood. In general I am almost always ultimately disappointed by these kinds of books, even by their better practitioners such as Waugh. I am just not thoroughly (wickedly?) cynical enough by nature to derive the full enjoyment from them. Besides the likelihood that they don't seem to age very well, for them to work the humor and thrust have to be quite sophisticated, I find, and this is where Waugh is strong. One of the oddities of our time is that Donald Trump would seem to be such an obvious target for a devastating satire, and truly millions of people are offering would-be witty and devastating commentary on his entire persona on a daily basis, yet I cannot remember anything of the sort that I thought was particularly funny or clarifying about the absurd situation we find ourselves in, not that I have read everything, of course. Trump is a slippery target I suppose because he genuinely seems (along with his supporters) to regard his detestable qualities as in fact great strengths, and this detail seems to be beyond the comprehension of his critics, which dulls their ability to mock him. Instead, the most delicious targets for satire in the current environment are the Resistance and the virtue signalers who regard themselves with hilarious self-seriousness as moral paragons, at least compared to their cultural and political enemies, and the guardians of the true Republic. Not that the Trumpists are not delusional too I suppose but the attacks on them are so obvious and predictable, I guess, they don't have any sophisticated force beyond brute rage....

This is the time of year when I start to count down the days I have left to read on the porch before I have to close that up for the winter. Most years I feel like I can get out there most days up to October 20th or so, but this year even the second half of September has been chilly. I've only gotten out there a couple of days each week the past fortnight, as there have been a lot of days where the high temperature was 57 degrees (and raining). It looks like there are two or three days coming this week which will be warm enough to go outside, but that might be it...

Monday, October 1, 2018

Author List Volume XV

Electra: Mycenae, Argolis, Peloponnese, Greece.

Rudolf Raspe (1736-1794) Baron Munchausen (1785) Born: Hanover, Lower Saxony, Germany. Buried: Killegy Churchyard, Muckross, Kerry, Ireland. College: Gottingen; Leipzig.

Baron Munchausen (1720-1797) Born: Munchhausen Museum, Muenchhausenplatz 1, Bodenwerder, Lower Saxony, Germany. Buried: Church, Kloster Kemnade, Bodenwerder, Lower Saxony, Germany. Munchhausen Landgut Dunte, Dunte, Latvia.

Charles Nordhoff (1887-1947) Mutiny on the Bounty (1932) Born: City, London, England. Buried: Hillside Memorial Park Cemetery, Redlands, San Bernardino, California. College: Harvard.

James Norman Hall (1887-1951) Mutiny on the Bounty (1932) Born: 416 East Howard Street, Colfax, Iowa. Buried: James Norman Hall Home, Arue, Tahiti, French Polynesia (Hill overlooking home). College: Grinnell.

William Bligh (1754-1817) Born: Plymouth, Devon, England. Buried: Garden Museum, St Mary's Church, Lambeth, London, England. Bligh Museum of Pacific Exploration, 876 Main Road, Adventure Bay, Bruny Island, Tasmania, Australia.

Emile Zola (1840-1902) Nana (1880) Born: 10 Rue St-Joseph, 2eme, Paris, France. Buried: Pantheon, 5eme, Paris, France. La Maison d'Emile Zola, 26 Rue Pasteur, Medan, Yvelines, Ile-de-France, France. Monument, Avenue Emile Zola (near Charles Michel Metro station), 15eme, Paris, France.

George Orwell (1903-1950) 1984 (1949) Born: East Champaran, Bihar, India. Buried: All Saint's Churchyard, Sutton Courtenay, Oxfordshire, England. George Orwell's House, Katha, Myanmar.

Kenneth Roberts (1885-1957) Northwest Passage (1937) Born: Storer Mansion, Storer Street, Kennebunk, Maine. Buried: Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, Virginia. College: Cornell.

Robert Rogers (1731-1795) Born: Methuen, Essex, Massachusetts. Buried: London, England (Gravesite lost). Rogers Island Visitors Center, 11 Rogers Island Drive, Fort Edward, Washington, New York. Rogers Rock, Lake George, Warren, New York.

William Hogarth (1697-1764) Born: Bartholomew Close, Smithfield, London, England. Buried: St Nicholas's Churchyard, Chiswick Mall, Chiswick, London, England. Hogarth's House, Hogarth Lane, Great West Road, Chiswick, London, England.

Cathedrale Notre Dame, 4eme, Paris France.

Odysseus Born: Ithaca, Ionian Islands, Greece.

Oedipus Rex Born: Thebes, Central Greece, Greece.

Robert Burns (1759-1796) Born: Robert Burns Birthplace Museum, Murdoch's Lone, Alloway, Ayrshire, Scotland. Buried: St Michael's Churchyard, Dumfries, Dumfries, Scotland. Burns Cottage, 16 Alloway, Ayrshire, Scotland. Writers' Museum, Lawnmarket, Lady Stair's Close, Edinburgh, Lothian, Scotland. Robert Burns Ellisland Farm, Holywood Road, Auldgirth, Dumfries, Scotland. Burns Monument, Kay Park, Kilmarnock, Ayrshire, Scotland.

Arnold Bennett (1867-1931) The Old Wives' Tale (1908) Born: Hope Street, Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, England. Buried: Burslem Cemetery, Burslem, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, England.

Aeschylus (525 B.C.-456 B.C.) Seven Against Thebes (467 B.C.), The Oresteia (Agamemnon, The Libation Bearers & The Eumenides, 458 B.C.) Born: Eleusis, Attica, Greece. Buried: Gela, Sicily, Italy (tomb not extant). Parco Archeologico della Neapolis, Via Paradiso 14, Syracuse, Sicily, Italy.

Agamemnon Born: Mycenae, Argolis, Peloponnese, Greece. Mask of Agamemnon, National Archaeological Museum, Athens, Attica, Greece.

Orestes Born: Mycenae, Argolis, Peloponnese, Greece.

Charles Robert Darwin (1809-1882) The Origin of Species and the Descent of Man (1859) Born: The Mount, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, England. Buried: Westminster Abbey, Westminster, London, England. Down House, Luxted Road, Down, Kent, England. Charles Darwin Research Station, Avenue Charles Darwin, Puerto Ayora, Ecuador. Colleges: Edinburgh, Christ's (Cambridge).

Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1913) Born: Llanbadoc, Wales. Buried: Broadstone Cemetery, Broadstone, Dorset, England. College: Birkbeck (London).

These lists are getting shorter as we move into the later volumes, as more of the books in them are by authors who have already appeared.

Rudolf Raspe (1736-1794) Baron Munchausen (1785) Born: Hanover, Lower Saxony, Germany. Buried: Killegy Churchyard, Muckross, Kerry, Ireland. College: Gottingen; Leipzig.

Baron Munchausen (1720-1797) Born: Munchhausen Museum, Muenchhausenplatz 1, Bodenwerder, Lower Saxony, Germany. Buried: Church, Kloster Kemnade, Bodenwerder, Lower Saxony, Germany. Munchhausen Landgut Dunte, Dunte, Latvia.

Charles Nordhoff (1887-1947) Mutiny on the Bounty (1932) Born: City, London, England. Buried: Hillside Memorial Park Cemetery, Redlands, San Bernardino, California. College: Harvard.

James Norman Hall (1887-1951) Mutiny on the Bounty (1932) Born: 416 East Howard Street, Colfax, Iowa. Buried: James Norman Hall Home, Arue, Tahiti, French Polynesia (Hill overlooking home). College: Grinnell.

William Bligh (1754-1817) Born: Plymouth, Devon, England. Buried: Garden Museum, St Mary's Church, Lambeth, London, England. Bligh Museum of Pacific Exploration, 876 Main Road, Adventure Bay, Bruny Island, Tasmania, Australia.

Emile Zola (1840-1902) Nana (1880) Born: 10 Rue St-Joseph, 2eme, Paris, France. Buried: Pantheon, 5eme, Paris, France. La Maison d'Emile Zola, 26 Rue Pasteur, Medan, Yvelines, Ile-de-France, France. Monument, Avenue Emile Zola (near Charles Michel Metro station), 15eme, Paris, France.

George Orwell (1903-1950) 1984 (1949) Born: East Champaran, Bihar, India. Buried: All Saint's Churchyard, Sutton Courtenay, Oxfordshire, England. George Orwell's House, Katha, Myanmar.

Kenneth Roberts (1885-1957) Northwest Passage (1937) Born: Storer Mansion, Storer Street, Kennebunk, Maine. Buried: Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, Virginia. College: Cornell.

Robert Rogers (1731-1795) Born: Methuen, Essex, Massachusetts. Buried: London, England (Gravesite lost). Rogers Island Visitors Center, 11 Rogers Island Drive, Fort Edward, Washington, New York. Rogers Rock, Lake George, Warren, New York.

William Hogarth (1697-1764) Born: Bartholomew Close, Smithfield, London, England. Buried: St Nicholas's Churchyard, Chiswick Mall, Chiswick, London, England. Hogarth's House, Hogarth Lane, Great West Road, Chiswick, London, England.

Cathedrale Notre Dame, 4eme, Paris France.

Odysseus Born: Ithaca, Ionian Islands, Greece.

Oedipus Rex Born: Thebes, Central Greece, Greece.

Robert Burns (1759-1796) Born: Robert Burns Birthplace Museum, Murdoch's Lone, Alloway, Ayrshire, Scotland. Buried: St Michael's Churchyard, Dumfries, Dumfries, Scotland. Burns Cottage, 16 Alloway, Ayrshire, Scotland. Writers' Museum, Lawnmarket, Lady Stair's Close, Edinburgh, Lothian, Scotland. Robert Burns Ellisland Farm, Holywood Road, Auldgirth, Dumfries, Scotland. Burns Monument, Kay Park, Kilmarnock, Ayrshire, Scotland.

Arnold Bennett (1867-1931) The Old Wives' Tale (1908) Born: Hope Street, Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, England. Buried: Burslem Cemetery, Burslem, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, England.

Aeschylus (525 B.C.-456 B.C.) Seven Against Thebes (467 B.C.), The Oresteia (Agamemnon, The Libation Bearers & The Eumenides, 458 B.C.) Born: Eleusis, Attica, Greece. Buried: Gela, Sicily, Italy (tomb not extant). Parco Archeologico della Neapolis, Via Paradiso 14, Syracuse, Sicily, Italy.

Agamemnon Born: Mycenae, Argolis, Peloponnese, Greece. Mask of Agamemnon, National Archaeological Museum, Athens, Attica, Greece.

Orestes Born: Mycenae, Argolis, Peloponnese, Greece.

Charles Robert Darwin (1809-1882) The Origin of Species and the Descent of Man (1859) Born: The Mount, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, England. Buried: Westminster Abbey, Westminster, London, England. Down House, Luxted Road, Down, Kent, England. Charles Darwin Research Station, Avenue Charles Darwin, Puerto Ayora, Ecuador. Colleges: Edinburgh, Christ's (Cambridge).

Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1913) Born: Llanbadoc, Wales. Buried: Broadstone Cemetery, Broadstone, Dorset, England. College: Birkbeck (London).

These lists are getting shorter as we move into the later volumes, as more of the books in them are by authors who have already appeared.

Thursday, September 6, 2018

September 2018

A List: Aldous Huxley--Time Must Have a Stop........................................61/311

B List: Ellen Glasgow--Barren Ground....................................................168/526

C List: H. R. Ellis-Davidson--Gods and Myths of Northern Europe........194/251

New books this month. Time Must Have a Stop was published in 1944, but it is set, thus far at least, in the 20s. I don't have a great sense yet of what it is about, but it features clever, eccentric characters of a certain epoch of English history who have enviable literary educations, so I appreciate that. The big drama in the book at the moment concerns a teenage boy who is unsuccessfully lobbying his brilliant but inattentive father to get him some evening clothes. Just before this I read two noteworthy short stories for the "A" list, "The Bulgarian Poetess" by Updike, which at one time at least was one of his more celebrated and most frequently anthologized stories, and "The Life You Save May Be Your Own", by the incomparable Flannery O'Connor. Updike reminds me of Graham Greene in the sense that he turned out a prodigious volume of professional writing over decades that seems as a rule to be worth reading for its own sake and contains its own interest almost independent of its subject matter. The premise of "The Bulgarian Poetess", in which an American writer briefly meets and is enchanted by the poet of the title at a conference behind the Iron Curtain to promote cultural understanding, which causes him to lament that they are not free to become better acquainted, seems rather quaint today, and is growing quainter by the hour, even though this was the world I grew up in until I was 19. Flannery O'Connor is one of the best writers of dialogue I have ever come across. It is artificial in the sense that almost no one ever talks like her characters do, or is capable of doing so, but the thoughts and conversations of those characters strikes one as what conversation, or writing, could attain if their practitioners always knew exactly what they wanted to say and what their purpose was in saying it. This is really one of the core principles of what literature is and why it is actually important, but I at least tend to lose sight of that.

I was looking forward to the Ellis-Davidson book, which is from 1964, a period whose scholarship in and interpretation of the humanities I have tended to trust for most of my life, though as that era grows ever more remote in time I am more able I think to see where their blind spots were at least even if I cannot wholly buy in yet to the more brashly asserted new developments and interpretations, where these exist. The book is in large part a survey in the style of Edith Hamilton, but less entertaining to read, drier, more academic, etc. I tend to doze off after 4 or 5 pages when I am reading it even though it is not uninteresting. I have largely given up trying to read late at night now because I can't stay awake, so this is happening in the afternoon. I don't fall asleep reading everything (yet), and I find that a good literary prose style is still able to engage me and keep me alert. But I suspect any denser philosophers and novelists are going to increasingly be a challenge for me.

I had been feeling healthier and somewhat more cautiously optimistic lately as the new school year started but I am a little off tonight.

B List: Ellen Glasgow--Barren Ground....................................................168/526

C List: H. R. Ellis-Davidson--Gods and Myths of Northern Europe........194/251

New books this month. Time Must Have a Stop was published in 1944, but it is set, thus far at least, in the 20s. I don't have a great sense yet of what it is about, but it features clever, eccentric characters of a certain epoch of English history who have enviable literary educations, so I appreciate that. The big drama in the book at the moment concerns a teenage boy who is unsuccessfully lobbying his brilliant but inattentive father to get him some evening clothes. Just before this I read two noteworthy short stories for the "A" list, "The Bulgarian Poetess" by Updike, which at one time at least was one of his more celebrated and most frequently anthologized stories, and "The Life You Save May Be Your Own", by the incomparable Flannery O'Connor. Updike reminds me of Graham Greene in the sense that he turned out a prodigious volume of professional writing over decades that seems as a rule to be worth reading for its own sake and contains its own interest almost independent of its subject matter. The premise of "The Bulgarian Poetess", in which an American writer briefly meets and is enchanted by the poet of the title at a conference behind the Iron Curtain to promote cultural understanding, which causes him to lament that they are not free to become better acquainted, seems rather quaint today, and is growing quainter by the hour, even though this was the world I grew up in until I was 19. Flannery O'Connor is one of the best writers of dialogue I have ever come across. It is artificial in the sense that almost no one ever talks like her characters do, or is capable of doing so, but the thoughts and conversations of those characters strikes one as what conversation, or writing, could attain if their practitioners always knew exactly what they wanted to say and what their purpose was in saying it. This is really one of the core principles of what literature is and why it is actually important, but I at least tend to lose sight of that.

I was looking forward to the Ellis-Davidson book, which is from 1964, a period whose scholarship in and interpretation of the humanities I have tended to trust for most of my life, though as that era grows ever more remote in time I am more able I think to see where their blind spots were at least even if I cannot wholly buy in yet to the more brashly asserted new developments and interpretations, where these exist. The book is in large part a survey in the style of Edith Hamilton, but less entertaining to read, drier, more academic, etc. I tend to doze off after 4 or 5 pages when I am reading it even though it is not uninteresting. I have largely given up trying to read late at night now because I can't stay awake, so this is happening in the afternoon. I don't fall asleep reading everything (yet), and I find that a good literary prose style is still able to engage me and keep me alert. But I suspect any denser philosophers and novelists are going to increasingly be a challenge for me.

I had been feeling healthier and somewhat more cautiously optimistic lately as the new school year started but I am a little off tonight.

Thursday, August 23, 2018

Charles Dickens--Barnaby Rudge (1841)

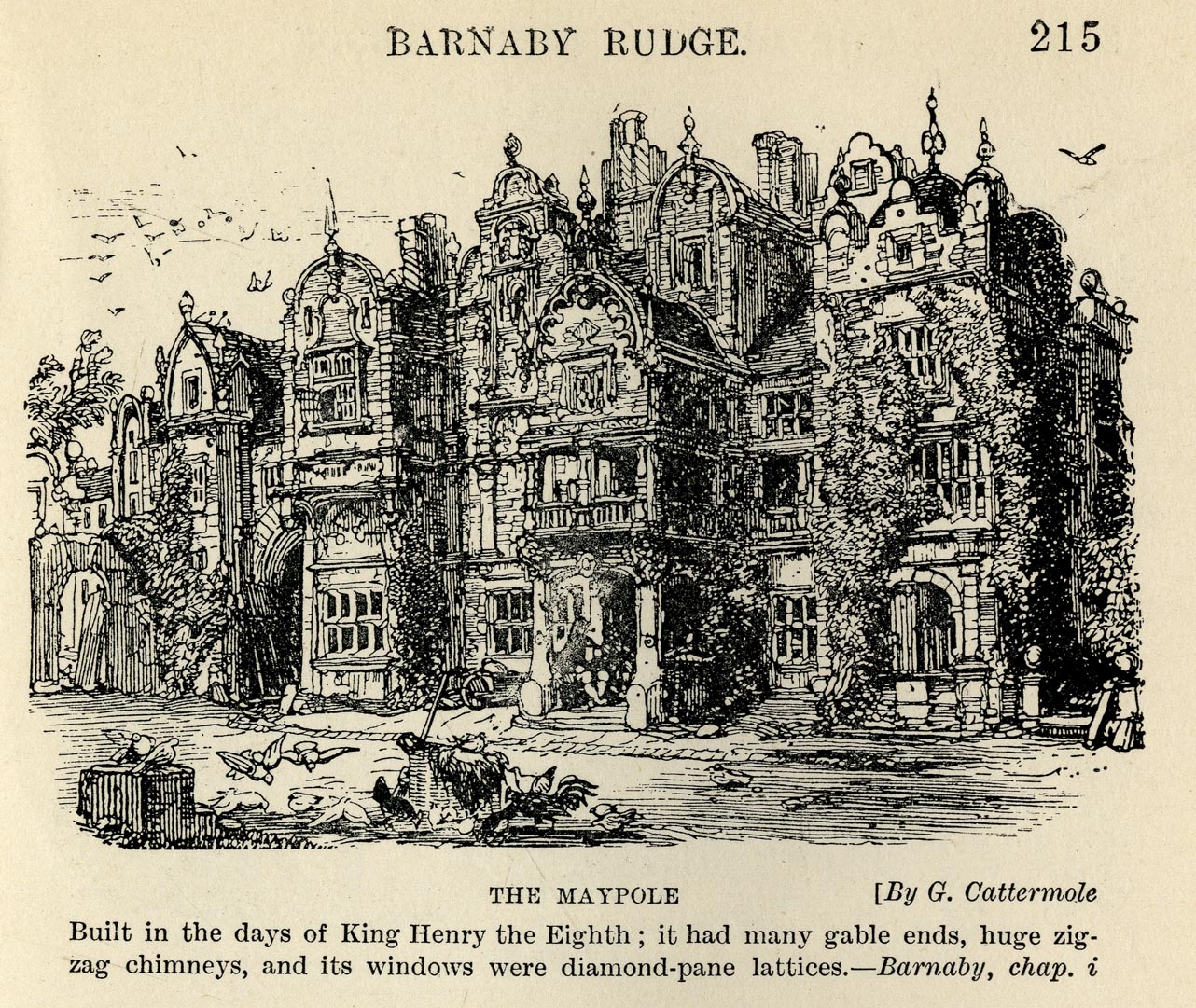

First Dickens on the list, of the nine I think that are on it. This was a good one to start with, as it is one of his celebrated efforts, and I had not read it before either. It is evidently not thought highly of by many readers, especially on the internet, but I liked it, as I tend to do with most Dickens books. I had thought that A Tale of Two Cities was his only book with a historical setting, but this one goes back to an even earlier event, the anti-Catholic riots that took place in London in 1780, which episode of history I must cop to being unfamiliar with. I don't even recall its coming up in the life of Johnson, though maybe it did. It's one of the early books, and the beginning especially I found to be very funny, reminiscent of the Pickwick Papers. The later parts were not as consistently humorous, but the accounts of the riots and their aftermath were compelling and full of interest enough, and while the story is not the smoothest flowing and the characters are not among his most renowned (though I thought John Willett and his cronies, Sir John Chester, Grip the Raven, the Maypole Inn, Mrs. Varden in the earlier parts of the book when she was relentlessly contentious, and even the ridiculous servant Miggs to some extent were skillful creations), the whole was still enviably lively and profuse compared to almost anything else.

The three main complaints about Dickens that I encounter online are that he was paid by the word (which encouraged a general overindulgence in his compositions), that too many plot points are resolved by coincidences, and that his depiction of women is simplistic and generally terrible. I have never found any of these objections to have a marked effect on my ability to enjoy the books, with the possible exception of the last one, as there are times, especially in the earlier books, where even I could wish for the female characters to be a little less insipid and have a more defined character. Barnaby Rudge is not one of his better efforts in this regard, the beautiful romantic interests Dolly Varden and Emma Haredale being little better than mannequins and ciphers, though the Dolly character was apparently very popular with readers at the time. I consider that he improved in this later on--Dora and Agnes in David Copperfield and Esther Summerson in Bleak House have a certain vividness to me years after reading those books. Dora is usually dismissed as being another insipid manic pixie dream girl type, but she was not stupid, only spoiled and overindulged, very much a type one encounters in real life, which cannot be said of most of the young women characters in the earlier books. As to the other criticisms, it appears that the oft-hurled epithet that Dickens was "paid by the word" is not technically true. He was paid to produce a certain amount of copy for the installments of his books, which is what the public in his time was buying, and presumably wanted. As I find his writing and personality amiable for the most part, and am used to the form of the Victorian novel, his alleged wordiness, which is often deployed in the service of some clever or ingenious observation or another, does not put me off. On the matter of his overuse of coincidences, this is a fairly ubiquitous device in literary productions before 1900, and even afterwards, and Dickens seems to me less egregious about it than other older writers, who depend upon it more for their grand effects. Their occurrence in him is usually an afterthought for me.

The Maypole was an inspired invention.

The first 200 pages or so of this were, as noted above, extremely funny. Sadly I neglected to take note of any specific examples for my report, though I suspect a good part of the humorous effect comes from having been set up beforehand in the overall flow of the book, episodes such as Sir John Chester's alighting from his coach after much over the top but entertaining demonstration of his gentility and paying the coachmen "something less than they expected from a fare of such gentle speech."

There is an elaborate and fine description in Chapter LI, too long to reproduce in full here, of the hapless Miggs's desperate efforts to stay awake while accompanying her mistress in sitting up late that is precise, funny, absurd, and mildly uncomfortable in its accuracy. A pointed example of the man's gifts as a writer.

Another one (example) is the depiction of the rioters as viewed from the rooftops in Chapter LXVII.

"...the crowd, gathering and clustering round the house: some of the armed men pressing to the front to break down the doors and windows, some bringing brands from the nearest fire, some with lifted faces following their course upon the roof and pointing them out to their companions: all raging and roaring like the flames they lighted up..." and so on. I think this is very good.

Whether intentionally or not, Dickens comes off as rather pro-establishment here, insofar as he is decidedly anti-rioters, these latter being depicted as a rabble of mostly ne'er-do-wells. The nature of the anti-Catholic sentiment supposed to have inspired the disturbance is easy enough to denounce. History as well as legend being famously written by the victors, rioters can reliably be painted or dismissed as being in the wrong, except when they aren't (the various rebellions of the 1960s come to mind, if most of these are even considered to be riots now). One of the disappointing aspects of this book was the rather unabashed class prejudice in it. The depictions of characters such as Miggs and the pathetic apprentice/would be revolutionary Tappertit are uncharacteristically (to my mind) and needlessly cruel. Meanwhile, the middle class characters who flirt with the movement manage to see where it is heading and distance themselves from it in plenty of time to remain untainted, and the conduct of two Catholic lords whose homes were burnt by the rioters and who refused to accept any of the money offered by the government in compensation were singled out for praise.

Dickens gave the estimated cost of the riots as being from 125,000 to 155,000 pounds, which I guess was a notable sum at that time.

Chapter LXXVII, the execution scene, with its description of the slow progress of the morning sun, the gathering of the crowd, their entertainments while waiting, etc. Also good.

Chapter the Last, of John Willett:

"He left a large sum of money behind him; even more than he was supposed to have been worth, although the neighbors, according to the custom of mankind in calculating the wealth that other people ought to have saved, had estimated his property in good round numbers."

I haven't mentioned the title character, Barnaby Rudge himself at all. He was an "idiot", less attuned to what was going on in the story than his pet raven, and my dislike of mentally limited characters, even when they appear in Dickens, is well documented. Neither he nor his mother brought anything to the story as far as I am concerned.

I have been collecting, and subsequently reading, volumes from the Oxford Illustrated Dickens series since the 90s. While these are new(er) books, they have the essential original illustrations as well as a classic readable typeface. Here is a picture of all my Dickens books from this set that I have acquired so far. On the shelf below you can see that I have the complete set of the Oxford Illustrated Jane Austen as well. Oxford also has put out a similar set of Mark Twain's works, but I don't have any of those as yet.

Here is Barnaby Rudge alone. I struggle with the phone camera to take a clear photo, especially in the surreptitious manner with which I take these photos, as I don't particularly care to be caught on a beautiful sunny day snapping pictures of books.

The Bourgeois Surrender Challenge

1. Scent of a Woman (movie)....................................................1,367

2. Mary E. Pearson--The Kiss of Deception.................................679

3. Bill Bryson--I'm a Stranger Here Myself.................................468

4. Rachel Vincent--My Soul to Lose.............................................192

5. Titans East Part I (Teen Titans: S 03 E 12 TV Show).............150

6. Peter Ackroyd--London: The Biography....................................98

7. Dafydd ab Hugh--Endgame (Doom)..........................................49

8. Victor Hugo--The Man Who Lives.............................................38

9. Annelisa Christensen--The Polish Midwife................................37

10. Ron Roy--The Runaway Racehorse..........................................31

11. Lindsay Hunter--Don't Kiss Me................................................31

12. Harold C. Goddard--The Meaning of Shakespeare, Vol. 1.......24

13. E. N. Joy--Lady of the House....................................................22

14. Work of Robert G. Ingersoll, Vol 1: Lectures............................19

15. Carol Marinelli--The Only Woman to Defy Him.......................14

16. Travis Kennedy--True Ghost Stories and Hauntings................14

1st Round

#16 Kennedy over #1 Scent of a Woman

The ghost story book--not my favorite genre--glides through with a shaky win.

#2 Pearson over #15 Marinelli

Battle of the genre books.

#3 Bryson over #14 Ingersoll

A halfway interesting matchup. Bryson's travel books are the kind of thing that the Challenge was created to give me an excuse to read from time to time.

#4 Vincent over #13 Joy

More genre books

#12 Goddard over #5 Titans

#11 Hunter over #6 Ackroyd

The Ackroyd book I have seen lauded, but he is the victim here of one of my dreaded upsets.

#7 Hugh over #10 Roy

Roy's is a children's book, but I would have given it the victory over an offering from the "Doom" series anyway. However, Hugh has an upset coming.

#9 Christensen over #8 Hugo

The Christensen may be a real book. Anyway she has an upset to pull out too. Victor Hugo's lesser known novels have now turned up several times on the Challenge, usually to be the victim of an early upset. I will have to keep watching for this trend.

Round of 8

#2 Pearson over #16 Kennedy

Because of the library factor.

#3 Bryson over #12 Goddard

The Bryson book appeals more to me at the moment. I haven't read a travel book in a while.

#11 Hunter over #4 Vincent

The library, surprisingly, gives the win to Hunter.

#9 Christensen over #7 Hugh

Final Four

#11 Hunter over #2 Pearson

Hunter is 300 pages shorter

#3 Bryson over #9 Christensen

The libraries don't carry Christensen anyway.

Championship

#3 Bryson over #11 Hunter

An anti-climactic final. However given that I am four or five books behind on the Challenge list, I am happy with the result.

The three main complaints about Dickens that I encounter online are that he was paid by the word (which encouraged a general overindulgence in his compositions), that too many plot points are resolved by coincidences, and that his depiction of women is simplistic and generally terrible. I have never found any of these objections to have a marked effect on my ability to enjoy the books, with the possible exception of the last one, as there are times, especially in the earlier books, where even I could wish for the female characters to be a little less insipid and have a more defined character. Barnaby Rudge is not one of his better efforts in this regard, the beautiful romantic interests Dolly Varden and Emma Haredale being little better than mannequins and ciphers, though the Dolly character was apparently very popular with readers at the time. I consider that he improved in this later on--Dora and Agnes in David Copperfield and Esther Summerson in Bleak House have a certain vividness to me years after reading those books. Dora is usually dismissed as being another insipid manic pixie dream girl type, but she was not stupid, only spoiled and overindulged, very much a type one encounters in real life, which cannot be said of most of the young women characters in the earlier books. As to the other criticisms, it appears that the oft-hurled epithet that Dickens was "paid by the word" is not technically true. He was paid to produce a certain amount of copy for the installments of his books, which is what the public in his time was buying, and presumably wanted. As I find his writing and personality amiable for the most part, and am used to the form of the Victorian novel, his alleged wordiness, which is often deployed in the service of some clever or ingenious observation or another, does not put me off. On the matter of his overuse of coincidences, this is a fairly ubiquitous device in literary productions before 1900, and even afterwards, and Dickens seems to me less egregious about it than other older writers, who depend upon it more for their grand effects. Their occurrence in him is usually an afterthought for me.

The Maypole was an inspired invention.

The first 200 pages or so of this were, as noted above, extremely funny. Sadly I neglected to take note of any specific examples for my report, though I suspect a good part of the humorous effect comes from having been set up beforehand in the overall flow of the book, episodes such as Sir John Chester's alighting from his coach after much over the top but entertaining demonstration of his gentility and paying the coachmen "something less than they expected from a fare of such gentle speech."

There is an elaborate and fine description in Chapter LI, too long to reproduce in full here, of the hapless Miggs's desperate efforts to stay awake while accompanying her mistress in sitting up late that is precise, funny, absurd, and mildly uncomfortable in its accuracy. A pointed example of the man's gifts as a writer.

Another one (example) is the depiction of the rioters as viewed from the rooftops in Chapter LXVII.

"...the crowd, gathering and clustering round the house: some of the armed men pressing to the front to break down the doors and windows, some bringing brands from the nearest fire, some with lifted faces following their course upon the roof and pointing them out to their companions: all raging and roaring like the flames they lighted up..." and so on. I think this is very good.

Whether intentionally or not, Dickens comes off as rather pro-establishment here, insofar as he is decidedly anti-rioters, these latter being depicted as a rabble of mostly ne'er-do-wells. The nature of the anti-Catholic sentiment supposed to have inspired the disturbance is easy enough to denounce. History as well as legend being famously written by the victors, rioters can reliably be painted or dismissed as being in the wrong, except when they aren't (the various rebellions of the 1960s come to mind, if most of these are even considered to be riots now). One of the disappointing aspects of this book was the rather unabashed class prejudice in it. The depictions of characters such as Miggs and the pathetic apprentice/would be revolutionary Tappertit are uncharacteristically (to my mind) and needlessly cruel. Meanwhile, the middle class characters who flirt with the movement manage to see where it is heading and distance themselves from it in plenty of time to remain untainted, and the conduct of two Catholic lords whose homes were burnt by the rioters and who refused to accept any of the money offered by the government in compensation were singled out for praise.

Dickens gave the estimated cost of the riots as being from 125,000 to 155,000 pounds, which I guess was a notable sum at that time.

Chapter LXXVII, the execution scene, with its description of the slow progress of the morning sun, the gathering of the crowd, their entertainments while waiting, etc. Also good.

Chapter the Last, of John Willett:

"He left a large sum of money behind him; even more than he was supposed to have been worth, although the neighbors, according to the custom of mankind in calculating the wealth that other people ought to have saved, had estimated his property in good round numbers."

I haven't mentioned the title character, Barnaby Rudge himself at all. He was an "idiot", less attuned to what was going on in the story than his pet raven, and my dislike of mentally limited characters, even when they appear in Dickens, is well documented. Neither he nor his mother brought anything to the story as far as I am concerned.

I have been collecting, and subsequently reading, volumes from the Oxford Illustrated Dickens series since the 90s. While these are new(er) books, they have the essential original illustrations as well as a classic readable typeface. Here is a picture of all my Dickens books from this set that I have acquired so far. On the shelf below you can see that I have the complete set of the Oxford Illustrated Jane Austen as well. Oxford also has put out a similar set of Mark Twain's works, but I don't have any of those as yet.