"Virgil has by many scholars been considered the greatest of all poets and the Aeneid was his greatest work...Virgil wrote in the classical Latin of the Golden Age." (IWE)

The Aeneid was the only work of the great poet's to be chosen for the 1958 reading list, however. It is also the only one of his that I have read as yet, though I am convinced that there is considerable greatness in the Eclogues and the Georgics, though like the Aeneid, the better part of this greatness is probably lost on anyone who is not very much at home in the Latin language. It is my impression that hardly anyone, at least who has a prominent public presence, knows Latin this intimately anymore, and even most among the super-educated do not seem to consider it a pressing issue. One result of this is that Virgil, one of the pillars of the Western intellectual tradition for two millenia, is rapidly becoming lost to the Culture (in an old post on the other blog relating to this same issue I used the phrase "any communal, non-specialist human consciousness" in place of Culture, to describe what he had been lost to), along with other Roman poets, Horace perhaps most prominent among these. I of course do not know enough Latin to read its literature without a translation myself. At this point I suspect most people hold some variation of the opinion that this kind of reading does not in most cases provide tangible value to a person's development--it is true I think that the amount of immersion and mastery that is necessary with regard to these studies to attain such tangible values as may be found therein is far greater than is generally appreciated even by people who would earnestly be interested in seeking them. Still, we are speaking of the widely acknowledged pinnacle of the literature of the language of the Roman Empire, the central language of Western thought for over a millenium after that empire's demise, one of the five great epic poems, traditionally considered to be the highest of all literary achievements, of Western/European history, a source of episodes and myths that recur throughout art and thought down through the ages. Surely all this would be of interest to some class of serious person...

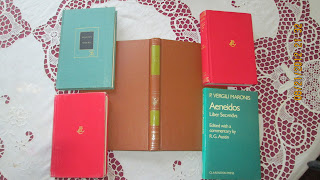

My collection of Virgil books. The first time I read The Aeneid, which was at the beginning of my sophomore year of college, I used the old Scribner's edition with the Rolfe Humphries translation, which I do not appear to have anymore. I have no idea when I jettisoned it. Maybe I didn't like it, although in my memory I had a fondness for it at the time, and the fairly clear memory I have of the physical book anyway would seem to confirm the truth of this. I also remember my wife, who would also have had to read this stuff, has having a copy of the Robert Fitzgerald translation, but we don't have this anymore either. Perhaps at one point a determination was made that one household only needs so many copies of Virgil, though this is not a usual position for us to take. The Brittanica Great Books set was part of another collection that someone (someone apparently quite wealthy, as I found a pay stub for $34,000 wedged into the pages of the first volume of Gibbon) had set out by the side of a rural road around where we live, and which we took up of course, because for us it is so reminiscent of school. On getting the books home though, we did discover that the Rabelais and Pascal volumes were missing; so the set is not complete. The Modern Library edition I think I bought at a library sale in Pennsylvania--I've had it for a very long time. I collect these, especially the ones from the 30s, 40s and 50s, not obsessively, but if I find a stray one in a box for a dollar, I'll pick it up. The translator of the Great Books edition is Rhoades, and that of the Modern Library is Mackail. I have not read either of these, though my impression from such contact with scholars and translation snobs as I have had is that they are not especially well-regarded.

The two red books obviously are from the Loeb Classical Library. In the summer of 1993, having a lot of idle time on my hands as I did not understand that I should be organizing my plans for after college, I came upon the harebrained scheme of trying to teach myself Latin by working line by line through the Aeneid. As I am very slow to catch on when things are not working, I did keep at it for a fairly long time--I did not finally abandon the effort until around the middle of Book Seven--but neither my knowledge of Latin nor understanding of Virgil progressed very far beyond dim child stage. The green book on the lower right is an Oxford University Press publication intended for the more advanced student. It is the Latin text of Book 2 only, with extensive notes on the grammar, word choices, disparities between manuscripts, comparisons with similar passages in other poets, and the like. I suppose I thought it would be some help to me.

This is a view of the train station in Mantua (Mantova), in Lombardy, taken from the window of a room on one of the upper floors of the ABC Albergo Hotel across the street, on March 2, 1997. Our poet was born in the village of Andes, which no longer exists and has for all intents and purposes long been absorbed into the city of Mantua, which is well established in the popular mind as the hometown of Virgil. At this time I was resident, I suppose it could be said, in Prague and had taken, during the winter break there, a trip to Italy, the prelude and beginning of which I wrote about here. After Venice we moved onto Florence for about four nights, after which it was Saturday, and sometime after lunch we finally made our departure from that city to start back towards Verona, where the bus that had brought us from Prague was awaiting to take us back there Sunday around 3 p.m. I generally like to take my time when visiting places and not try to cram too much in, but I noted that Mantua was only about thirty miles from Verona so as we had walked around the center of Verona on the first day I thought it would be a great idea to spend the last night in Mantua, look around on Sunday morning and zip over on the train in time to catch the bus in the afternoon. This was before one arranged everything on the internet beforehand, or at least before I did, but it seemed easy enough...

The above is supposed to be a likeness of Virgil. The building, which is the Palazzo Broletto, according to my book, or the Palazzo del Podesta, according to the internet, dates from the 1200s, which impresses me, though it is nothing in this part of the world.

We arrived in Mantua sometime in the evening, probably seven or eight. We wandered around for quite a while searching for what was to me an acceptably cheap hotel, but there weren't any, for Mantova is one of the richest cities in the richest region in Italy. Thus we ended up at the hotel across from the train station, which was 95,000 lira, or less than $50 as it was, but that was a veritable fortune to me at the time. There was a freaking telephone in the room! In truth we were running low on funds at this point, but we were able to get a pizza and some cheap wine in a place equal parts pleasant and raucous adjoining the train stations. I love train station restaurants; of course everything--the station, the surrounding district of the town, and the restaurant--has to be old, the way it would have been before 1965, where they frequently serve as settings in movies and novels. Many of the old cities in Italy have happily not had their ancient plans, at least in their central parts, as much improved upon in recent decades as those elsewhere have.

Picture of me back when I was at least thin underneath Virgil's niche, and a slightly expanded view of the palazzo. I am still favoring the shapelessly fitted earth tones that were the fashion among some people in the early 90s. Spring of '97 was about the time all of that really began coming to an end, though those kinds of shifts are way too subtle for me to pick up on in real time. When seeing youthful pictures of myself like this, I am happy that I at least had the opportunity to go to some of these places when I was still young, and I have some good memories of them, but they are always accompanied by the knowledge that I did not begin to make the most of those opportunities in any way. This is off-topic, but I was watching the movie Chariots of Fire recently, and wondering why it had such a powerful effect on people of middling intelligence and accomplishment, myself included, but induced diffidence at best in most people who operate at a world-class level, and it struck me that the appeal of the movie to middlebrows was that it shows people who appear to be maximizing their potential, in various areas of life, at every instance of those lives that is shown on the screen, which is actually quite rare in movies, but are at the same time not doing anything in a way that seems completely inaccessible to bourgeois audience members. Holding one's own with the toffs at Cambridge seems (in this movie anyway) like a skill one could learn if one was exposed to them enough and had the right kind of instruction at the necessary stages of life. Anybody could be as devout a Christian as Eric Liddell--there isn't even competition involved to prevent you from attaining this goal--if it were possible for him to derive satisfaction from that kind of life, which most people will dismiss out of hand. Even winning the Olympics is not such a daunting task when the only people you have to beat are graduates of elite universities from about eight countries, and the likes of Usain Bolt aren't going to be walking through the door. Anyway, in most of the important areas of life--the physical, the intellectual, the sensual, the social, the active useful--I spent most of my formative years watching from the fourth row back on the sideline.

The above is the main square in old Mantua, with the duomo on the left and the palazzo of the doge, or duke, or whatever the person was called that ruled the city back in the Medieval/Renaissance era. As you can see hardly anyone is out, because it is Sunday, and places like Mantua completely close down on Sunday in Italy, as well as much of the rest of Europe. This particular visit, pleasant though it was in many ways, was a reminder that one should always plan on Sunday to be in or on the way to a big city, or at least a fairly popular one. Nothing was open. We had to go back to our pizzeria of the night before but we only had enough cash left (after buying our train tickets) to get a tiny plain pizza and tap water--ATMs in the provinces did not work for foreign bank cards on Sundays at that time either.

Statue of Rigoletto. This house had a connection with Verdi. He used it as a set model for many of his operas. I don't know why, however, which would be a slightly more interesting tidbit to know.

Mantua is an ancient city, and there are blocks of medieval streets and buildings that are not exactly obsessively preserved. There were, as I have noted several times, very few people out on the streets, and the majority of the population that one did see were senior citizens. Even at that time the birthrate in the prosperous areas of northern Italy were historically low--less than 1 child per woman in nearby Bologna, and I doubt it was much more than that in Northern Lombardy and one saw very few children, and these almost always single children accompanied by three or four adults. The preponderance of old people was very noticeable.

This is part of the modern Virgil monument, which was apparently commissioned by Mussolini in 1927, though I was not aware of this at the time, or did not make the connection. I can't make out the verse inscribed on the plinth anymore, but I am going to make a guess that the figures represented here are supposed to be Aeneas and Turnus (or perhaps Mussolini and Georges Clemenceau, whom the Turnus figure somewhat resembles).

I've always wanted to slip this disclaimer in in one of my blog posts, that I am aware I have a terrible whining problem, and always have, and that most people from St John's, and this is one of the qualities I find most admirable in my old schoolmates, are, like my wife, most decidedly not whiners, and are generally competent and achieve above-average success as adults. It is a very fine school for people who understand how to work and have a strong connection to areas of life outside of the college. Our students of this description tend to do very well in the world, and contribute to society in substantial ways. The college even helps its many alumni who are lazy, delusional, emotionally needy and frightened of most aspects of regular American society to lead a far more bearable life than they would likely have been able to manage without it; but it can only do so much.

The whole of the Virgil monument. I did think this commanding depiction of Virgil seemed a little out of sync with his traditional reputation as a lover of the quiet, rural life. This is located in a large park adjacent to the old part of town. It was the last thing we saw before heading back to the train station.

My ingenious plan to make it back to Verona in time for the bus did not proceed entirely smoothly. First of all, even though the two cities are just 30 miles apart, the main train lines that they lie on are separate. There is a branch line that runs between the two cities as a kind of local. However it only runs a couple of times on Sunday. Then of course, Mussolini not being in charge of the country anymore, the trains did not run on time, and as there was no one else waiting in the station, including, at that point, the people in the ticket booth, this girl was not too happy with me, and was dubious that any train was going to Verona that day at all, though the posted schedule in the station indicated that one indeed ought to be arriving imminently.

I wait in the empty station. Needless to say the train did come, and we did make it to Verona on time, though barely--the other passengers were already seated on our bus when we pulled in. The ride between the two cities through the farmland of the Po Valley was ungodly beautiful and evocative of myriad things about Europe and Western Civilization that I had presumed to be over, and that I still presume will be over soon enough, but boy did it take its time getting there. This was not one of those high-speed trains zipping across the Euro-countryside that so much is made of. No, this was decidedly retro.

Behind the Chiesa di Santa Maria di Piedigratta in Naples (near the Mergellina subway station, it looks like) there is a Roman grotto in which one of the monuments is traditionally called Virgil's tomb. It is not, actually, but it has been referred to as such since the 1100s, and it is still maintained with a certain amount of reverence, so I am going to count it. Besides, I don't have a lot of sites in Naples on my list, and I want all the excuses to make it there someday that I can get.

No comments:

Post a Comment