When I was a young child and my parents would go to some other adults' house (which they did far more than I ever do), especially if they did not have children around my age (which seemed to be the case most of the time), if there were nothing else to amuse me, they would drop me by the host's bookcases and tell me to find something to my taste. Usually this would mean a sports book or perhaps a history book with a lot of pictures, but I did go through a stretch where I became fond of certain kinds of books of plays and would be excited to come upon one of those. Almost everyone seemed to have at least some volume of Shakespeare, but as an eight or nine year old I didn't care for that, due to the length of the speeches and the difficulty of the language. If there were nothing else I would give it a try but I never got much out of these, other than becoming somewhat familiar with the lists of characters. The real jackpot was to come across an edition of popular midcentury American plays, which were written more like the television programs I was used to, and best of all was to find something like "30 One Act Plays for School Groups" (most of my parents' acquaintance were teachers) which I remember as being invariably wholesome and having satisfying endings. I would imagine all of the roles as being played by the most vivid kids from my school who would fit them, though with myself of course always as the star. This period didn't last more than a year or two at most, but I was reminded of it when reading this, as it the kind of play I would have liked to have come upon that time, though I don't recall ever doing so.

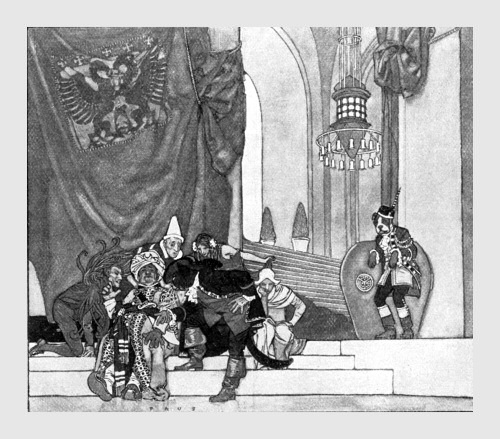

Maurice Maeterlinck was a Belgian author who won the Nobel Prize in 1911 at the age of 48--they used to give it regularly to much younger writers than has been the case recently. The Blue Bird was overall his most celebrated work, but some of his earlier plays from the late 1880s and early 1890s seem to be well regarded. In the words of the IWE, "A fairy-tale play for children is the best-known and most surely immortal work of the Belgian Nobellian. It gave the world a phrase, 'the blue bird of happiness,' and its moral is that the blue bird is to be found at home, be it ever so humble. The play is excellent for performance by schoolchildren in large schools because it offers an almost unlimited number of parts, costume parts at that. It can easily accommodate 200 performers. But it demands elaborate sets and machinery for professional performance. When it is properly produced it is quite a spectacle." Though I had not been attentive to it before, if it had ever come up at all, I have come across two instances of someone using the expression "blue bird of happiness", since I read this, including one who tossed it off in the course of ordinary speech. So I guess it is still somewhat alive.

The style of dialogue was reminiscent to me of Samuel Beckett's writing. Very spare, with a lot of exchanges consisting of each speaker uttering speeches of 1-3 simple words in turn for several pages. Maeterlinck was a proponent of what he called "the static drama", which downplayed emotion in favor of emphasizing the external forces that acted on man. Samuel Beckett certainly strikes me as having some relation to this tradition, though obviously taken to a much more relentless and unsettling extreme.

p. 72--The Land Of Memory. The children, passing through here on their quest to find the Blue Bird, encounter their dead grandparents. "Why don't you come to see us oftener?...It makes us so happy...It is months and months now that you've forgotten us and that we have seen nobody."

The idea of the Land of Night--diseases, fears, etc, that have largely been conquered by human knowledge--I thought was worthy of being remarked on. It is an optimistic, pre-World War I nod to progress. Although Maeterlinck lived until 1949, he doesn't appear to have written anything considered to have much literary value after the first World War, though his books still sold well in France through the 1930s.

p. 130 I thought the catalog of the trees and their various personalities: the poplar, the birch, the chestnut, the beech, the elm, etc, was very good. The eloquence of the stark depiction of the elements of the (sensitive?) child's world, physical, cultural, emotional. I am now sure that literary and artistic minded people in our age are as attuned to this, in their own manner, as any old European writer was, but I do like this particular expression of it.

p. 186 "Here is the Happiness of Loving One's Parents, who is clad in grey and always a little sad, because no one ever looks at him." In the Palace of Happiness, there are various Happinesses who appear as characters, among them the Happiness of Being Well, the Happiness of Pure Air, the Happiness of Innocent Thoughts, the Happiness of the Winter Fire, and on and on. I noted the characterization of the Happiness of Loving One's Parents, because I am myself guilty of not allowing myself to feel this, even though there is no reason not to other than that I have always been unhappy about my lack of talents and attractive qualities that might have given me some of the social standing and respect I would have liked to have had. But I just can't overcome that.

p. 204-5 Fire's role in death. "I am used to burning them...Time was when I burnt them all; that was much more amusing than nowadays..." "Fire, in particular, would want to burn the dead, as of old; and that is no longer done." Of course it is going back the other way now. I still personally recoil in something (can't read my note) against the idea of cremation and would prefer to be buried, but due to cost, changing mores, concern for the environment, etc, it probably will happen the other way. I don't know why the thought of being burned bothers me, especially it would eliminate any chance of my being buried without actually being fully dead, which is something to avoided for sure.

p. 246-7 This is the part where they encounter all of the babies preparing to be born. There are two of these babies, one boy and one girl, who were lovers and always embracing, and had to be forcibly separated in order to be born, never fated to meet on the earth. This was reminiscent to me of the incels, some number of whom are wont to speculate about the possibility that some potential girlfriend of theirs may have been aborted and things of that nature. Somebody I went to school with called me, or least my younger self, an incel within the last year, which I don't think was really fair, or quite accurate when considering the crowd going by that designation now, but obviously the impression was made.

I have a note here to "comment on worldviews therein ([word I can't read] of fire, bread, etc) in light of current cultural reassessment." I don't remember what I was referring to here. I should note again that during the fairy part of the story, Fire, Bread, Sugar, Water, and so on are live characters who have elaborate costumes and speak, as well as the Dog and the Cat. Apart from the Dog, who is unshakeably loyal to the humans and regards the little boy as his god, the other characters do a fair amount of complaining about their relation to and usage by man and attempt from time to time to abandon him. Overall the story does not promote an idea of struggle, but presents an idea of the world as something to marvel at and full at all times of unseen and unnoticed energies and passions and phenomena that are sources of wonder and strength, while much of what is immediately visible is crude and distracting and were best overcome. I am not sure how this relates to the current cultural reassessment, beyond that people don't seem to have time for this kind of miniaturist approach to thinking about the world and their own lives, but I really do not often have consistent ideas about anything from day to day.

There have been numerous film versions of this play, the most notable being the silent 1918 adaptation directed by Maurice Tourneur, a 1940 version starring Shirley Temple, which turned out to be the first box office flop of her career however, and an animated Soviet movie from 1970. I don't think the story has remained familiar to modern audiences however.

So with the completion of this report I have now reached the end of Volume 3 (out of 20) in the progress of this list. Volume 3 took me about 2 and a half years to complete, which is about 6 months longer than I got through each of the first two volumes. At my current pace I wouldn't be able to get through the whole list until I was 88, which is an age I am not going to make it to. These months of quarantine and having everyone home all the time have not helped this either. Still, if I can make it through a few more years, I should have more time to read these books and write these reports faster. I know there are at least a couple of very long (although very great) books coming up in Volume 4, but the first few that I see include a number of plays and very short novels, so perhaps I will be able to get back on a doable track.

The Bourgeois Surrender Challenge

1. Dale Carnegie--How to Win Friends and Influence People...............…...............16,982

2. The Words (movie-2012)..................…............................................................…...7,724

3. Mary C. Neal--To Heaven and Back...….............................................................…3,264

4. Kate Danley--The Woodcutter...........................................................................…..1,880

5. The Village (movie--2004).................................................................................…..1,327

6. Arnold Lobel--Frog and Toad Are Friends............................................................…496

7. Pamela Aidan--An Assembly Such as This..................................................................356

8. Jack London--"To Build a Fire"...............................................................….........…..128

9. Erin Hunter--Survivors (novel series).....................................................................….114

10. Colleen Coble--The Mercy Falls Collection.........................................................…104

11. Zen Cho--The True Queen..........................................................................................55

12. Patricia Marx--Him Her Him Again the End of Him.............................................…..43

13. Isabella L. Bird--The Hawaiian Archipelago..............................................................33

14. Paul Higgins--No More Bile Reflux........................................................................…28

15. Dawn Brower--One Heart to Give........................................................................…..24

16. Lara Richard--A Chance For Him........................................................................…...24

Round of 16

#1 Carnegie over #16 Richard

#15 Brower over #2 The Words

#3 Neal over #14 Higgins

#13 Bird over #4 Danley

#12 Marx over #5 The Village

#11 Cho over #6 Lobel

I own and have read Frog and Toad Are Friends, which is a children's book. I don't care for it that much, as it is a series of understated, repetitive stories in which virtually nothing happens, but my children seemed to like them well enough when I would read it to them, so I guess there is something to it.

#7 Aidan over #10 Coble

Aidan's book is Jane Austen fan fiction, it is about characters from Pride and Prejudice, etc, which is a genre of story that I am not inclined to like at all, but it has an upset.

#8 London over #9 Hunter

We have this Survivor series as well, though I have never read them. My wife tried to get one of my reluctant sons to read them a few summers ago, but I don't think he made it very far in them.

Round of 8

#1 Carnegie over #15 Brower

#3 Neal over #13 Bird

The Neal book, despite the romance novel title, appears to be a spiritual book about angels and that sort of thing. It is very short.

#12 Marx over #7 Aidan

Marx was a comedy writer for the New Yorker and Saturday Night Live. I doubt I would find her particularly funny, and would probably find her writing smug and sanctimonious--most people in this vein of the culture seem to fall naturally into this character nowadays (though this book is from 2006 at least)--but I am sure it is more endurable than Jane Austen fan fiction.

#8 London over #11 Cho

Final Four

#1 Carnegie over #12 Marx

This was a pretty close match, but the Carnegie is kind of a classic, and I have never read it, and that will carry it to a win here.

#8 London over #3 Neal

Championship

#8 London over #1 Carnegie

In this battle of publishing heavyweights, London's story wins by being even more of a classic, and one which, rather incredibly, I have also never read.