So we come to Ben-Hur, a book that I bought a copy of (part of the green and gold spined 20 volume 1930s era "World's Greatest Literature" Series) at a barn sale in 1986 and, especially after I went to college, did not think for a long time that I would ever actually read. But having come to the point a few year's back where I had lost much of my enthusiasm for developing any further in a higher or more future-oriented direction, I came back to some of the unfinished business of childhood years which set me on the road, five and a half years later, to today's post.

As I mentioned in one of my monthly reports, even though I had owned this book for thirty years I had not really noticed how long it was, and if I ever had, I probably wondered if my edition was not abridged, because I always imagined it to be a doorstop type of book. But my edition was only 488 pages, and contained the whole book. The IWE introduction avows that "It is not great literature", but also asserts that "it would be hard to imagine anyone's packing more action into a single volume" The first statement is certainly true, the second is misleading, as if the book were fighting and other forms of physical exertion and struggle from one end to the other, when in fact there are long stretches of wandering and searching and decidedly non-violent episodes from the Bible. It does have a manly energy and thrust to it that compensates for some of its deficiencies, its author having been a general in the Civil War and President Arthur's ambassador to Turkey (joining Hawthorne and Irving, at least, as American authors who served as foreign ambassadors). The IWE, in its upbeat postwar way, refers to Wallace as "a successful Union general", which seems to be putting an extremely positive spin on the matter as he was accused of committing a major blunder at Shiloh, the most significant battle in which he took part, which resulted in a high number of casualties, the castigation of Ulysses S. Grant himself, and the removal from command for almost two years. And even when he returned to active command in 1864, his troops were defeated in the main battle (Monocacy) in which he took part, though he was credited with delaying the rebel force enough to prevent it from attacking Washington.

The book is written in a heavy 19th century style that is difficult to read if one's body has any inclination to go to sleep. Nonetheless I am so far gone in my nostalgic fantasies about the blue skies and epic vistas alike about the ancient world and pre-1960 literature and my own youthful ideas that when I can stay awake and concentrate for any amount of time I really do enjoy it. Manly contention as well as camaraderie among equals, or near enough equals, in strength and spirit, especially against the backdrop of great historical scenes, cities, empires, etc, is always inspiring or is at least a reminder of that feeling when one could believe in it.

As is often the case, I did not take any notes until page 377, then took quite a few over the last 100 or so pages. Sometimes it takes going through almost the whole book to figure out what the questions raised are.

1st note, p.337 "To the purely Christian nature the presentation would have brought the weakness of remorse. Not so with Ben-Hur; his spirit had its emotions from the teachings of the first law-giver, not the last and greatest one. He had dealt punishment, not wrong, to Messala."

p. 351 "As the mind is made intelligent, the capacity of the soul for pure enjoyment is proportionally increased...Wherefore repentance must be something more than mere remorse for sins; it comprehends a change of nature befitting heaven."

If a living priest or some other person in real life were to say these things to me in 90% or more of any such instances I would despise them, I have no doubt. Yet coming across them in the dead pages of a book they, and the belief system that they evidently represent, are soothing.

p. 361 "A country of hills changes but little; where the hills are of rock, it changes not at all."

p. 418 "The Egyptian has him in her net...She has the cunning of her race, with beauty to help her--much beauty, great cunning; but, like her race again, no heart. The daughter who despises her father will bring her husband to grief."

The despised father to boot is Balthasar, of the famous group The Magi. Wallace is an extremely pro-Jewish writer, especially in the religious sense, vis-à-vis almost all of the other nationalities that appear in this book.

p. 419 "A man drowning may be saved; not so a man in love."

p. 424 "In his eyes there were tears which he would not have them see, because he was a man."

Maybe my favorite sentence in the book. Upon Ben-Hur's accepting that his mother and sister are dead, though actually they aren't.

p. 442 "He persisted as men do yet every day in measuring the Christ by himself. How much better if we measured ourselves by the Christ!"

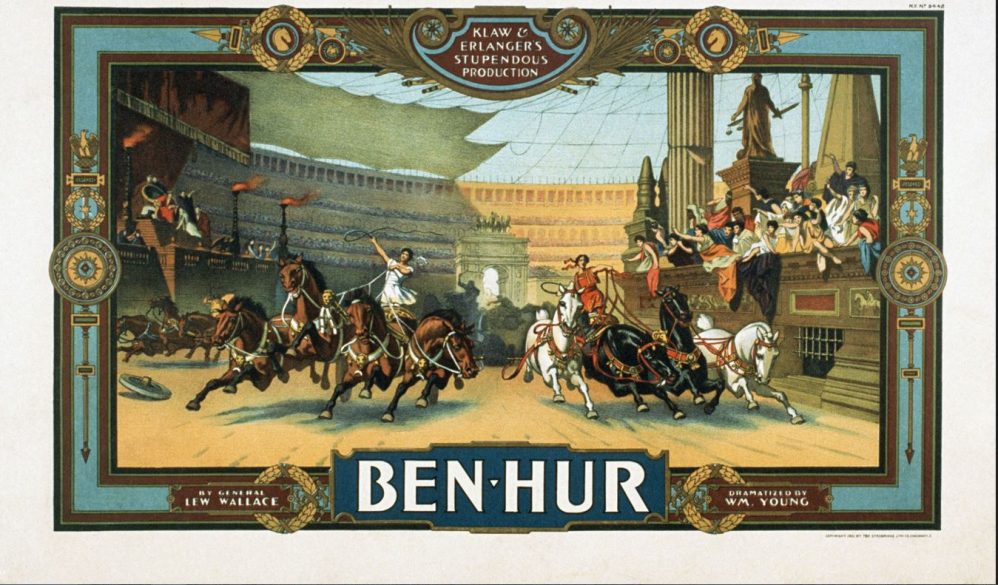

The chariot race is the big action scene in the book as well.

I am about to speak heresy (it is a wicked and godless age), but why do we so easily excuse God/Christ for not immediately overthrowing the Roman power? Modern analytics/efficient practices would suggest that, in the absence of any proof of heaven that would be accepted on Twitter, that would have been a more optimal outcome for humans, though I suppose a worse story. Despite all of the forceful arguments asserting that Jesus Christ, if he ever existed, was the biggest phony in the annals of human history, that belief in supernatural religion is a joke, that spirituality is an invention of the human imagination and has no basis in science and so on, and that this is essentially what almost all genuinely intelligent people in today's world understand to be true, I have never been able to come around to ridiculing the pointless and misguided march of religious, and especially Christian history, which seems to me too important and powerful an--often for good--influence in human culture and psychological makeup to treat so callously. In fact I am admiring and often envious of the truly seriously religious, who seem to me to have a surer sense of who they are than all but the most intellectually invulnerable materialists, whose conception of the nature of the world within which they have found satisfaction is as yet too intricate for me to follow.

According to Wallace's autobiography, he was raised in the Christian tradition but wasn't a devout follower, and he does not appear to have been a member of any church. There are claims on the internet that he was an atheist who wrote Ben-Hur to disprove Christianity, which does not appear to be true, and which I do not believe anyway. Ben-Hur did almost to the last hour cling to the belief that Christ would either lead or inspire in the Jewish people a successful earthly rebellion against the Roman Empire, and he expressed more disappointment about this even after he realized to some extent what Jesus was doing than I would have expected, but the point was not to illustrate that Christianity was wrong so much as that it was difficult to comprehend and to live by.

p. 447 "The idea, old as the oldest of peoples, that beauty is the reward of the hero had never such realism as she contrived for his pleasure..." The evil, tempting, exotic "other" Egyptian again.

To further comment on my thought above, I wrote "the humbling of Ben-Hur's worldly ambitions something of a surprise ending to me. It is more emphasized than in the film.

p. 477 "The sun was rising rapidly to noon; the hills bared their brown breasts lovingly to it..." At the crucifixion, which I thought was effectively described as a physical ordeal. Perhaps the soldier's sense at work?

The final paragraph of the book is a brief personal note from the author which I found warming. Most of these writers never address the reader so directly.

"If any of my readers visiting Rome, will make the short journey to the Catacomb of San Calixto, which is more ancient than that of San Sebastiano, he will see what became of the fortune of Ben-Hur, and give him thanks. Out of that vast tomb Christianity issued to supersede the Caesars."

The Challenge

1. David Mitchell--Cloud Atlas..................................................................…..2,317

2. Edward Gibbon--Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire........................…..746

3. Simon Sebag Montefiore--Jerusalem: The Biography...……..................…..422

4. John Julius Norwich--Sicily: An Island at the Crossroads of History...…….111

5. David Graeber--Bullshit Jobs........................................................................…71

6. Margot Lee Shetterly--Hidden Figures (children's book edition)......….……..66

7. Bodie & Brock Thoene--Eighth Shepherd........................................................64

8. Robert Audi--Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy....................................….36

9. Bill Myers--Devoted Heart...........................................................................….20

10. Teyla Branton--Insight.................................................................................…17

11. G. J. Whyte-Melville--The Gladiators............................................................10

12. Monica Selveira Cyreno--Big Screen Rome...………………………………...7

13. Matthew S. Hedstrom--The Rise of Liberal Religions.................................….5

14. Alexa Person--The Zero Point.....................................................................….5

15. Georg Ebers--Serapis...……………………………………………………….2

16. Works of Lucian of Samosata...……………………………………………….2

Round of 16

#1 Mitchell over #16 Lucian

Lucian is worthy of some respect, his works being part of the Loeb classical series in eight volumes. Eight volumes is lot to overcome against any literary competition in this game, however.

#2 Gibbon over #15 Ebers

Gibbon is one of the last of the inner circle pre-1900 English language classics that I have never read. Its massive length is going to work against it in this format also. I know that I am going to get to it on my "A"-list at some point in the next 10-20 years, so I don't feel the pressure to read it sooner rather than later tightening around me yet.

#3 Montefiore over #14 Person

#4 Norwich over #13 Hedstrom

Hedstrom has no library presence, cannot compete.

#5 Graeber over #12 Cyreno

Big Screen Rome sounds like it might be an interesting book, but no one has it, and the Graeber book, despite its ungenteel and mildly abrasive title, is not one I can eliminate immediately on the basis of near certain dislike.

#6 Shetterly over #11 Whyte-Melville

The Shetterly is a children's picture book edition of the recent adult best-seller and mild sensation--perhaps that would have been a better entry in the tournament, but it was not the one that made it. Whyte-Melville's book, not available in any libraries, looks like another densely written, highly moralized triple decker Victorian novel with a Roman setting, just like Ben-Hur. While I don't mind one of these kinds of books on occasion, there are enough of them sitting on the IWE list that I don't need to add any additional ones for my "free reading".

#7 Thoene over #10 Branton

#8 Audi over #9 Myers

There is not much use for dictionaries on this kind of list, but the Myers book is, for the purposes of this list, a meatball, not being in libraries, being a genre book that does not appear to be published by an outlet with any stature, and thus cannot realistically defeat anything with the Cambridge imprimatur.

All the higher seeds win in the 1st round. The field was lopsided.

Elite 8

#1 Mitchell over #8 Audi

#2 Gibbon over #7 Thoene

If Gibbon keeps drawing red state American Christian novelists, he may triumph in this contest after all.

#3 Montefiore over #6 Shetterly

#4 Norwich over #5 Graeber

Norwich's Sicily book is reasonable in length, and its 29 extra pages over Graeber's are not enough to make us consider the upset.

Final Four

#1 Mitchell over #4 Norwich

Norwich would actually have won this based on shorter length, but Mitchell has the only upset to play in this entire tournament.

#3 Montefiore over #2 Gibbon

Even the Montefiore book is 650 pages. Gibbon proves a tough out in his 1st Challenge appearance.

Championship

#1 Mitchell over #3 Montefiore

Another pretty long book (509 pages) added to the wait list, but the shorter entries need to come through quality-wise. Also Mitchell is about my age and enjoyed the kind of literary success and critical adulation, at that time anyway--maybe he still does, or does any novelist really have that kind of status for life anymore?-- that I used to imagine must be my eventual lot, so looking into his book will be a kind of reckoning for me.