This is the third Eugene O'Neill play thus far in the IWE list, and there are many more to come, I think there are around ten altogether. It is also another American play of the 20s and 30s, another Pulitzer Prize winner--the third so far in the drama alone!--and of course O'Neill was a Nobel Laureate as well, all of which is in keeping with some of the already established themes running through this great list. I had had for some reason the impression that Anna Christie had been his breakout play, but in fact he had already won another Pulitzer Prize two years earlier for Beyond the Horizon and that was followed up by The Emperor Jones before Anna was produced as well. This play struck me in reading as generally less interesting and more dated, in a negative sense, than the two O'Neill plays I have previously read for this project, with which I was impressed. This is one of the works of his that features a more brutish and not especially appealing class of character in whom it is difficult for the earnest, well-meaning, socially aspirant reader of the modern day to find much hope of development. Still, I did not dislike the experience of going through it. O'Neill does give a certain quality of darkness and heaviness of detail to the atmosphere of this older America that has a ring of authenticity in it to me and that other authors do not hit at in quite the same way.

It is strange to me for some reason to imagine an America where heavily accented Swedish and other Scandinavian immigrants make up a not inconsiderable segment of the society, yet many books from this 1880-1930 period attest that this was a vivid part of the national scene in those years. No doubt one of the reasons that this literary era does appeal to me so much, even down to its secondary works, is that it is when people of my general ethnic type, Irish/German/Baltic Sea area, were most ascendant and more culturally vital than they seem to be at present. A lot of characters in books from this time, perhaps because their physical characteristics and responses to various stimuli are simply described better than they are by modern writers, seem much more akin to me than most contemporary people, let alone literary characters, do. It is not a major consideration, and it not something I really picked up on until I started reading more of these books again over the past couple of years. I was often struck by how many characters had blue eyes. I have seen it put forth that around 50% of Americans were blue eyed in 1900 as opposed to only 16% today. This is the kind of fact that one isn't supposed to find interest or meaningful, I guess, though I think it is interesting at least. The circumstance that I think it interesting implies that I probably find it meaningful too, but I am not going to begin to speculate on the form that might take here, because I have not really thought about it very much. Perhaps one of these books will prod me to have some further thought about this later on.

While the plots are not exactly identical, some of the similarities between Anna Christie and the 1928 Josef Von Sternberg silent film The Docks of New York seem too striking to be coincidental. Both feature a fallen blonde and a ship's stoker of almost inhuman physical strength who get involved with each other. Both have as a major setting a rough seaman's bar on the New York waterfront. One has a bartender named Johnny-the-Priest, the other has a preacher type among the bar's cast of characters named Hymn-Book-Harry. Docks of New York is officially an adaptation of a short story by another writer named John Monk Saunders. There is not a lot of biographical information on Saunders, though he was married for eleven years to King Kong star Fay Wray (!--she played the girl--writers, how you have fallen!), and hanged himself at age 42. He sounds to me like he has alcoholic written all over him, though I cannot find confirmation of this, which would have made channeling the literary spirit, as well as output, of Eugene O'Neill somewhat easier.

Greta Garbo (who played in a lot of the film versions of the books on this list that have become somewhat obscure)

For the execution of this reading, I turn to a trusty old 1950 Modern Library edition of three of Eugene O'Neill's plays, with an introduction by Lionel Trilling. Unlike modern introductions by scholarly editors that batter the reader's will to live under an assault of critical theory and erudition of obscure books and characters and movements (real erudition is simply knowing everything, or nearly everything, central to the varied subjects that the ideal university graduate is supposed to know but most never get around to actually learning; obscurities are by definition not essential, and therefore do not display erudition, unless they can be demonstrated to somehow be essential), Trilling in a few broad sentences acknowledges what difficulties the general reader of 1950 (i.e., me) will find in a conventional reading of the play as play ("...its central incident--the regeneration of a cynical prostitute--is now timeworn and not especially interesting in itself, and the virtues of its poetic language are surely questionable"), and explains in clear and simple language why the show was important in its time, in a way that enhances at least my active interest in reading it ("(O'Neill's) Style, indeed, was sufficient content...all constituted a denial of the neat proprieties, all spoke of a life more colorful and terrible than the American theatre had ever thought of representing." Speaking of the zeitgeist of the 1920s: "It was a movement of cultural protest, against the business civilization of America, against philistinism, puritanism and vulgarity... Essentially a revolt of the conscious middle class against its own sterile complacency, it offered the promise of a regenerative cultural life.")

Long (9 minute) clip from the 1923 film version of Anna Christie, starring Blanche Sweet.

The Challenge

Another challenge that is all over the place and produces very few 'real' books.

1. Safe Haven (movie)............................................................1,454

2. Patrick Leigh Farmer--A Time of Gifts..................................190

3. Salman Rushdie--The Ground Beneath Her Feet.................142

4. Samanthe Beck--Best Man With Benefits..............................133

5. Berenstain Bears--God Bless Our Country.............................54

6. Jasper Ridley--Brief History of the Tudor Age........................23

7. ed. Peter Haining--The Mammoth Book of True Hauntings....14

8. C. Lee McKenzie--Sudden Secrets..........................................13

9. Jan Wahl--Humphrey's Bear......................................................7

10. Sam Llewellyn--Clawhammer.................................................1

11. Nicholas Karolides--Literature Suppressed on Political Grou.1

12. Anastasia--Master of the Universe: Memoirs Book 1..............1

13. Eugene O'Neill--The First Man................................................0

14. Mary Ellen Snodgrass--Encyclopedia of Gothic Literature.....0

15. Victoria Tan--So This is Death.................................................0

16. The Hopeline--Understanding Self-Worth...............................0

Round of 16

#1 Safe Haven over #16 Hopeline.

I am not sure that the Hopeline book actually exists.

#2 Farmer over #15 Tan.

Tan may not be an actual book either. The Farmer meanwhile seem to be something of a minor classic.

#3 Rushdie over #14 Snodgrass.

I have never read anything by Rushdie. He should be able to comfortably advance over an obscure academic exercise, especially in the first round.

#13 O'Neill over #4 Beck

One of O'Neill's lesser remembered plays evidently, though it is probably possible to find a copy of it. I may even have a copy of it in one of my various collections.

#5 Berenstain Bears over #12 Anastasia

The Berenstain Bears are players in the publishing world. They'll beat anything the relationship of which to a traditional book is foggy to me.

#6 Ridley over #11 Karolides

Based on nothing, other than that it sounds more interesting.

#10 Llewellyn over #7 Mammoth Book of Hauntings.

#8 McKenzie over #9 Wahl.

Teen trash over blah-looking children's book.

Performance of Anna Christie in what I imagine to be modern dress.

Round of 8

#13 O'Neill over #1 Safe Haven

#2 Farmer over #10 Llewellyn

#3 Rushdie over #8 McKenzie

#6 Ridley over #5 Berenstain Bears

This round was pretty clear cut. The Llewellyn book might be good, but my curiosity is aroused too greatly by the Farmer.

Final 4

#13 O'Neill over #2 Farmer

There is not a copy of the Farmer book anywhere in a library in the State of New Hampshire, even though it has received the what I thought to be imprimatur of the New York Review of Books reprint series.

#3 Rushdie over #6 Ridley

No one is holding the Ridley book either. A disappointing Final Four.

Championship

#3 Rushdie over #13 O'Neill

At 575 pages the Rushdie book is a little long, and by the ordinary rules of the challenge would not win here. However, he has appeared in the Challenge several times already without winning, and we read so much O'Neill in this program--nine or ten plays I am guessing--that while I am curious to read one of his lesser known works, I feel an obligation to take on some modern novels from time to time in the course of this game.

Monday, April 25, 2016

Wednesday, April 13, 2016

Margaret Landon--Anna and the King of Siam (1944)

Probably best known today as the source material for the famous musical The King and I, Anna and the King of Siam would I suppose belong to the genre of historical fiction, as Anna Leonowens was an actual person who was employed at the court of the King of Siam in the 1860s, and the novel was largely based on her memoirs of that experience. The book was surprising to me, in a positive sense, in a number of ways. Though I had always seen it on the list and knew it was coming I had not paid close attention to it. It was published much later, for example, than I imagined it was. While I knew it was set roughly around the time that it is, I had thought the publication dated from the late Victorian era to 1910 or so at the latest. This is probably on account of the musical; I tend not to think of musicals in general as based on particularly fresh material. though most of the Rogers and Hammerstein shows were actually based on sources, or events, that were only a few years old. I also, again probably because of the musical, which I in fact have never seen, as well as its inclusion in the family-friendly IWE list and the circumstance of its general lack of consideration as serious literature, imagined the book as more oriented towards children, or at least adolescents, with considerable sugar-coating or romantic treatment of its subject, but in fact the routinely sadistic abuses and executions that are inflicted on members of the royal harem and other slaves are depicted quite graphically, to the point really that you find yourself asking, "Why is this English woman staying here and continuing to work in this environment anyway?" The book is genuinely interesting, for the most part--it may be slightly too long in the sense that a couple of episodes perhaps could have been left out. It is in the main episodic, without a tight thread of a central plot or action driving the characters forward and together, which style I don't mind, only that some episodes are more compelling than others. Many of the minor characters, both Siamese and European, will crop up again in a later episode a hundred pages or more after they had previously appeared, and whether this is due to advancing age and declining memory or not I have trouble remembering them when they reappear. I could use one of those lists of characters that often appear after the table of contents in Dickens or Tolstoy novels, in which books, ironically perhaps, I never have trouble keeping the characters straight or remembering who they are.

Not knowing anything about Siam in this time period, even its relation to European colonial aggression, I thought Landon did a good job in sketching a general outline of this through the character of the king's correspondence with Western governments, the introduction to the very small expatriate communities centered around the British and American and French consulates, and the handful of highlighted instances and crises of mainly French agitation against Siamese territory. It attests to some skill in the author that after witnessing King Mongkut having people burned to death and tortured and thrown into dark dungeons for interminable periods of time for trifles mostly related to a lapse of absolute self-effacement in deference to his Majesty that this reader was able to feel sympathy for him when the French representatives are applying pressure to him to accede to various outrageous demands. I am reminded, as I often am in old books written by English speakers, of the brusque arrogance of the French ruling classes in the days when that country was a world power. Of course the French have retained a reputation for hauteur and snootiness into our own time, but it lacks something of the force, as well as the seething visciousness, that this characteristic is depicted as possessing in these old books. I have no doubt that the British in their heyday were no less obnoxious and condescending after their own fashion, though the effect on reading about it is usually not so pronounced, even in the most nationalistic of the Irish writers; and on the whole they don't seem to have inspired quite the thorough degree of visceral hatred in the people they have formerly abused or made to feel inferior as the French (this is not to say that a visceral hatred does not exist, I merely postulate that it does not attain the same intensity as that directed towards the French).

Given that this book is 1) written by a woman; 2) is about a woman, and one who actually existed and was independent and seems to have been possessed of considerable pluck; 3) takes place in a non-Western country and seems to attempt to give an accurate presentation of the nature of life there; and 4) has at the very least some claim to literary distinction as much I think as other books that are considered to be important, my impression is that it is not widely read or remembered today. Is it somehow too racially offensive or insensitive or otherwise politically problematic? Landon, presumably writing through, or guided by the spirit of Anna Leonowens, was at least on the right side of history in thoroughly denouncing slavery and European colonialism, though by the end of World War II when the book was published these views were not terribly out of the mainstream. The Siamese or Thai people are treated I think with seriousness, though the repressive, authoritarian society that predominated in the palace does not show the country in a flattering light; I have no reason however to suspect it was not broadly accurate. Students of White Privilege would have a field day with Anna Leonowens, as she wields this status or aura throughout her stay in Thailand like one of the European gunboat cannons that so terrifies King Mongkut. All of the Siamese people have to spend half their lives in various forms of simpering prostration and submission to the wills of whoever ranks above them and can be tortured or killed on a whim, but Anna is perfectly confident to walk into this brutal environment and declare that none of these customs apply to her (which, as it turns out, is largely correct). Anna also has in her a considerable amount in her of the now notorious but at that time largely unconscious White Woman Savior complex when placed among people whose culture and enlightenment have not yet attained to the level favored by the European upper middle classes. Much is made in the book of her determination, through her teaching the future princes and other ministers of the Siamese state, to impress upon them certain European humanistic ideals the lack of which were especially offensive to her in the Siamese court, which had the result, according to the book, that when her pupil Prince Chulalangkorn ascended the throne, he abolished slavery and the more outrageous customs of prostration throughout his domains, this being credited to the influence of Anna. So this might be too much European righteousness for modern readers to take.

I found a very nice wartime copy of the book, with its lighter paper and increased words per page per the restrictions of that period, at my nearby used book barn. It has charming illustrations at the beginning of each of the forty chapters, as well as a quaint map of Bangkok in the 1860s. This edition must have been the one that sold the most copies, since I see on the internet that this is the one that most of the people who read the book have.

Example (sort of) of the illustrations in the book. I assume there must be a Blogger app I can put on to post pictures from my phone, since I have a phone now. I need to figure out how to do this so I can just out on my own pictures from now on.

Strictly as a point of curiosity to me, Margaret Landon lived to the age of 90, dying on December 4, 1993 in Alexandria, Virginia (this, incidentally, was the same day that Frank Zappa died). It's curious to me because I would have been a senior at college at that time in Annapolis, only about 40 miles away. This day was a Saturday near the beginning of the Christmas holidays, so it possible that I played a basketball game that afternoon and I almost certainly went to a party that evening. I don't remember exactly what happened on that day but I can surmise that it was probably a pretty good one as far as days in my life go. It's one I would be willing to live over again.

Rex Harrison rocks the role of the king in the 1st film version of Anna.

The Challenge

Among the magic words in the synopsis of Anna and the King of Siam were frequent repetitions of "slave", "ransom" and similarly grim terms, which led to a rather lackluster field for the tournament this time.

1. Exodus: Gods and Kings (movie)........................................................2,837

2. Her (movie)..........................................................................................1,569

3. Anna and the King (movie).....................................................................363

4. Marylu Tyndal--The Ransom..................................................................244

5. Sharon Penman--A King's Ransom.........................................................215

6. Travels of Marco Polo.............................................................................150

7. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Arden Edition, ed. Katherine Duncan-Jones).....86

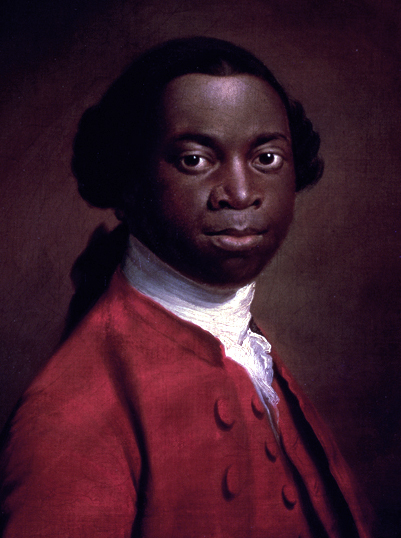

8. The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano.......................55

9. People's Almanac #2.................................................................................15

10. Edward D. Johnson--The Handbook of Good English............................13

11. Complete Works of Lord Byron...............................................................11

12. Frances Calderon de la Barca--Life in Mexico.........................................8

13. Grand Funk Hits (record).........................................................................6

14. Sword and Sorcery: The Divine and the Defeated...................................5

15. Deidre Knight--Parallel Fire....................................................................5

16. Evelyn Anthony--The Cardinal and the Queen........................................3

Michael Millner's Fever Reading procured no points and thus failed to qualify for the championship. However it did have a naked woman overwrought from her reading on the cover, so it gets an honorable mention here.

1st Round

#16 Anthony over #1 Exodus

#15 Knight over #2 Her

#3 Anna and the King over #14 Sword and Sorcery

Breaking my usual rule about movies not being able to beat books because I am not counting the Sword and Sorcery thing as a real book.

#4 Tyndal over #13 Grand Funk

I don't really like any Grand Funk songs.

#5 Penman over #12 Calderon.

Calderon should have won in a cakewalk over this genre book. but Penman had an upset in reserve.

#6 Polo over #11 Byron.

Complete works of poets don't really fit in with the Challenge in the way that I read these books, in Byron's case especially, as a couple of his longer poems are on the regular list in their own right. The Polo book interests me somewhat.

#10 Johnson over #7 Shakespeare.

I am giving it to Johnson by a hair, as my library does not have the Arden edition of the Shakespeare.

#8 Equiano over #9 People's Almanac #2.

Final 8

#16 Anthony over #3 Anna and the King

#4 Tyndal over #15 Knight.

Neither of these books registers anywhere in the New Hampshire State Library database.

#10 Johnson over #5 Penman.

#8 Equiano over #6 Polo.

The Equiano book, which appears to be a slave narrative, is almost 200 pages shorter than the edition of Polo that is available to me.

Final 4

#16 Anthony over #4 Tyndal

#8 Equiano over #10 Johnson

Championship

#8 Equiano over #16 Anthony.

Wednesday, April 6, 2016

April Update

A List: Between books currently.

B List: Anna and the King of Siam--Margaret Landon 360/391

C List: The Age of the Democratic Revolution: The Struggle--R. R. Palmer 136/578

The last thing I read for the "A" list was the poem, or collection of poems, known as "The Passionate Pilgrim", attributed on the original title page to Shakespeare, but which is in fact a compilation of a number of poets of the time, including Shakespeare, and also including some unknown authors. It has the famous lines "Were kisses all the joys of bed/one woman would another wed" which it seems cannot be positively attributed to Shakespeare, but still usually is by the general public. I read it in my clunky Rockwell Kent-illustrated complete Shakespeare, which is the only book I own that contains it. It is printed there as if it were a regular part of the Shakespeare canon, though without any introduction or notes. I was a little confused in reading it by the incoherence between various parts of the poem and the lack of continuation of various characters and motifs throughout the work, as well as the inclusion of some lines that were obviously from Marlowe's "Passionate Shepard to his Love", so I was glad to have some explanation for this.

The Landon book I am almost finished with and will be doing a full report on soon.

The Palmer, subtitled A Political History of Europe and America, 1760-1800, is the second, and last, volume of the Challenge-winning book I was reading last month. So far I am actually liking this second volume more than the first, in part I suspect because I am used to the style now, and also because the second volume deals directly with the events of the French Revolution and the general European war that accompanied it, which is of course a very dramatic episode of history that I have somewhat shamefully never read even a general history of. Robespierre is best remembered now for overseeing the reign of terror, but he was a compelling political animal, perhaps a genius of that art in some ways, who made some great and memorable speeches. More than a few of his bons mots have a startling resonance today, not least because they are more lucid and succinctly expressed than most prominent contemporary thinkers have been able to manage on similar topics. "Equality of wealth is a chimera...necessary neither to private happiness nor to the public welfare". But "the world hardly needed a revolution to learn that extreme disproportion of wealth is the source of many evils." More: "We want an order of things...in which the arts are an adornment to the liberty that ennobles them, and commerce the source of wealth for the public and not of monstrous opulence for a few families...In our country we desire morality instead of selfishness...the sway of reason rather than the tyranny of fashion, a scorn for vice and not a contempt for the unfortunate...good men instead of good company, merit in place of intrigue, talent in place of mere cleverness...the charm of happiness and not the boredom of pleasure...in short the virtues and miracles of a republic and not the vices and absurdities of a monarchy."

He rather humorously dismissed the spectacle of the Worship of Reason held in the desacralized Notre-Dame Cathedral in 1793 as "a philosophical masquerade".

He also famously said that "Revolutionary government owes good citizens the whole protection of the nation. To enemies of the people it owes nothing but death."

Palmer theorizes that Europe became afflicted with revolutionary fervor at the end of the 1700s rather than at an earlier time because too many people of some degree of capability had come to feel personally humiliated by existing political and social arrangements. I do believe that something like that is occurring now throughout the Western World, where the middle classes, at least, are not suffering from material deprivation or physical insecurity, yet there is a great amount of anxiety and dissatisfaction that I think is rooted in greater-than-ordinary (compared to, for example, 1964 when this book was published) feelings of humiliation, inferiority and powerlessness among the populace. Of course if I continue to believe this to be the case I will eventually have to make a stronger argument for it...

Picture Gallery

B List: Anna and the King of Siam--Margaret Landon 360/391

C List: The Age of the Democratic Revolution: The Struggle--R. R. Palmer 136/578

The last thing I read for the "A" list was the poem, or collection of poems, known as "The Passionate Pilgrim", attributed on the original title page to Shakespeare, but which is in fact a compilation of a number of poets of the time, including Shakespeare, and also including some unknown authors. It has the famous lines "Were kisses all the joys of bed/one woman would another wed" which it seems cannot be positively attributed to Shakespeare, but still usually is by the general public. I read it in my clunky Rockwell Kent-illustrated complete Shakespeare, which is the only book I own that contains it. It is printed there as if it were a regular part of the Shakespeare canon, though without any introduction or notes. I was a little confused in reading it by the incoherence between various parts of the poem and the lack of continuation of various characters and motifs throughout the work, as well as the inclusion of some lines that were obviously from Marlowe's "Passionate Shepard to his Love", so I was glad to have some explanation for this.

The Landon book I am almost finished with and will be doing a full report on soon.

The Palmer, subtitled A Political History of Europe and America, 1760-1800, is the second, and last, volume of the Challenge-winning book I was reading last month. So far I am actually liking this second volume more than the first, in part I suspect because I am used to the style now, and also because the second volume deals directly with the events of the French Revolution and the general European war that accompanied it, which is of course a very dramatic episode of history that I have somewhat shamefully never read even a general history of. Robespierre is best remembered now for overseeing the reign of terror, but he was a compelling political animal, perhaps a genius of that art in some ways, who made some great and memorable speeches. More than a few of his bons mots have a startling resonance today, not least because they are more lucid and succinctly expressed than most prominent contemporary thinkers have been able to manage on similar topics. "Equality of wealth is a chimera...necessary neither to private happiness nor to the public welfare". But "the world hardly needed a revolution to learn that extreme disproportion of wealth is the source of many evils." More: "We want an order of things...in which the arts are an adornment to the liberty that ennobles them, and commerce the source of wealth for the public and not of monstrous opulence for a few families...In our country we desire morality instead of selfishness...the sway of reason rather than the tyranny of fashion, a scorn for vice and not a contempt for the unfortunate...good men instead of good company, merit in place of intrigue, talent in place of mere cleverness...the charm of happiness and not the boredom of pleasure...in short the virtues and miracles of a republic and not the vices and absurdities of a monarchy."

He rather humorously dismissed the spectacle of the Worship of Reason held in the desacralized Notre-Dame Cathedral in 1793 as "a philosophical masquerade".

He also famously said that "Revolutionary government owes good citizens the whole protection of the nation. To enemies of the people it owes nothing but death."

Palmer theorizes that Europe became afflicted with revolutionary fervor at the end of the 1700s rather than at an earlier time because too many people of some degree of capability had come to feel personally humiliated by existing political and social arrangements. I do believe that something like that is occurring now throughout the Western World, where the middle classes, at least, are not suffering from material deprivation or physical insecurity, yet there is a great amount of anxiety and dissatisfaction that I think is rooted in greater-than-ordinary (compared to, for example, 1964 when this book was published) feelings of humiliation, inferiority and powerlessness among the populace. Of course if I continue to believe this to be the case I will eventually have to make a stronger argument for it...

Picture Gallery

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)