It is frequently observed (and almost as frequently disputed) that men in our time are something quite different from what they were formerly. I tend to be in the camp that believes some fairly drastic changes have occurred, due both to alterations in mode of life as well as biochemical influences. While a fantastical and somewhat out-of-date fiction even by the standards of its own day, Beau Geste, the huge best-seller of the 1920s, is animated nonetheless by infectious qualities of male spiritedness, camaraderie, acceptance of the possibility of death and craving for adventure, and a general attitude of celebration of the possibilities of upper class European manhood. The IWE felt compelled to note that "Wren was by no means a good writer" even as they were championing his book, and it is true that he lacks a smooth style or incisive insights or other literary qualities of that sort, but I found the book to be unique and interesting in many places. Even the construction of it is rather bizarre in that the first 80 pages involve a stereotypically suave and jaunty French officer relating a mysterious escapade in the desert to an old English chum of equal social and military rank, at which point the narrative finally shifts to the Geste brothers, the protagonists of the book, with the two characters who opened the book not seen again except for a few cameo appearances. And even within the brothers' story, the title character Beau, while the leader of the group and possessed of the most heroic qualities, is not really the central figure around whom most of the narrative is centered, that being John, the younger brother, who narrates the entire second portion of the book and whose movements we always remain with even during lengthy periods when Michael, or Beau, is offstage.

But as I said, there is much that is attractively lively in the book, and compared to most of the works on this program, it was a very fast read: it took me about 2 weeks to get through 418 pages, which is a pace I have not approached since before I had children.

At one point I thought I was going to get through this one with very sparse notes but I ended up filling a page with them.

From page 9, a sample sentence:

"And then as I wearily light a wretched cigarette babbling I know not what of a wretched Arab goum--they are always dying of fatigue, these fellows, if they have hurried a few miles--on a dying camel, who cries at the gate that he is from Zinferneuf, and that there is siege and massacre, battle, murder, and sudden death."

I assure you, I would have thought this just as wretched as everyone else does fifteen or twenty years ago.

p. 40 "Duty to my country came before my duty to these fellows, and I must not allow any pity for their probable fate to come between my and my duty as a French officer."

Do we argue so viciously now because we are all strangers pitted one against the other? The camaraderie of class/school/profession, when it takes hold, seems stronger in old books than anything of the sort that we know now.

p. 125 "'I've let Augustus take the blame all this time', she sobbed" "'Didn't notice him taking any,' observed Digby. 'Must be a secret blame-taker, I suppose.'"

When running away to join the French Foreign Legion the narrator raises money for the adventure by going to a Jewish pawnbroker, the portrait of whom is predictably unflattering. The IWE summarizer observed that "among other things" Wren's "effort to render American conversation was ludicrous even for an Englishman" though this was pointedly the only ludicrous rendition of conversation that was pointed out.

p. 155 "'I gotter live, ain't I?' he replied, in a piteous voice, to my cruel look." "Forbearing to observe 'Je ne vois pas la necessite', I laid my stick and gloves on the counter..."

p. 157 "Personally, I would always rather travel first class and miss my meals, than travel third and enjoy three good ones, on a day's journey. Nor is this in the least due to paltry exclusiveness and despicable snobbishness. It is merely that I would rather spend the money on a comfortable seat, a pleasant compartment, and freedom from crowding, than on food with cramped circumstances."

p. 175 "He was of a type of Frenchman that I do not like (there are several of them)..."

This drew an LOL from me.

p. 193 "I liked him less and less as the evening wore on, and I liked him least when he climbed on the zinc-covered counter and sang an absolutely vile song, wholly devoid of humour or of anything else but offence. I am bound to admit, however, that it was very well-received by the audience."

Another chuckle.

p. 197 " A huge greasy creature, grossly fat, filthily dirty in clothes and person, and with a face that was his misfortune, emerged from the cooking-house. he eyed us with sourest contempt."

Wren allows the reader to indulge his natural dislike of ugly, stupid people with terrible personalities.

To put the life of the no longer very well known Wren into some context, he was born in South London in 1875 and lived until 1941. His father was a schoolmaster, and he received a Master's degree from St Catherine's Society, described by Wikipedia as a non-collegiate institution for poorer students. He worked for the Indian Education Service from 1903 to 1917. He was appointed a reserve officer in East Africa for less than a year during the First World War. His supposed service in the French Foreign Legion, out of which experience this book and many of his other top-selling literary productions were thought to have sprung, appears never to have been confirmed. He appears to have begun publishing his adventure novels around 1914. He cut a preternaturally dashing figure in the few photographs of him that are known.

p. 208 "It struck me that community of habits, tastes, customs, and outlook form a stronger bond of sympathy than community of race; and that men of the same social caste and different nationality were much more attracted to each other than men of the same nationality and different caste..." The proto-globalism of the French Foreign Legion.

p.213 "'But why bother about the Americans? They are uncultivated people.' 'We're going to cultivate them,' punned Michael."

p. 234 "We made rapid progress and, after a time, made a point of talking Arabic to each other. It is an easy language to learn, especially in a country where it is spoken." I have no idea whether this is true or not. In my life I don't know any Anglophones who have learned to speak it. It is of course necessary to the plot that the Geste brothers learn it.

p. 250 Another sample passage of the rip-roaring, swashbuckling variety: "Possibly we were going to take part in some complicated scheme of conquest, extending French dominion to Lake Tchad or Timbuktu. Possibly we were about to invade and conquer Morocco once and for all...We were keen, we were picked men, and nobody went sick or fell out. Had he done so, he would have died an unpleasant death, in which thirst, Arabs, and hyenas would have been involved."

p. 253 "I should have liked to admire him as much as I admired his military skill, and ability as a commander, and I began to understand how soldiers love a good leader when it is possible to do so." Well put, and an important idea to remember.

p. 289 "'Do you swear it by the name of God? By your faith in Christ? By your love of the Blessed Virgin? And by your hope for the intercession of the Holy Saints?' asked Bolidar." "'Not in the least,' replied Michael. 'I merely say it. I have not got a diamond--'Word of an Englishman.'" We had to have something like this get in at some point. It is humorous but not ironic or arch or any of that. I appreciate it.

p. 337 John to Beau when they are the last two men in the fortress alive as it is being besieged. "...it's been a great lark." Beau is an attractive character, but as noted above, not fleshed out or very deep, or even particularly prominent on a page by page basis in the story.

p. 364 "I did my best to make it a real 'Viking's Funeral' for him, just like we used to have at home. Just like he used to want it. My chief regret was that I had no Union Jack to drape over him."

I did make a note around this point asking What is this book about? but I am sure I was overthinking the question because it is about the romance of young male blossoming, adventure, daring, and death, a subject which, in this kind of treatment anyway, does not seem to be of much positive interest to the contemporary gatekeepers of the culture. It is of interest to me, however!

p. 368 "I greatly feared that our deeds of homicide and arson had raised us higher in the estimation of these good men than any number of pious acts and gentle words could ever have done."

I thought it was also noteworthy that it was not treated as terribly important that the high-spirited and eminently sharp and capable Beau should survive the adventure and return home to found a family line and take up a leading role in the affairs of his country. This is the role of his less immediately dynamic brothers, though the whole family was plenty resourceful and insouciant on their own.

Beau Geste has been adapted for numerous major movie and T.V. productions. The first was a silent version in 1926 starring Ronald Colman. My copy of the book was a companion to the release of this film and includes several still photographs from it among its pages. Another major Hollywood version came out in 1939, starring Gary Cooper, Ray Milland, and Robert Preston, with direction by William Wellman. Hollywood did another remake in 1966 without big stars, although future TV legend Telly Savalas appeared as the sadistic commander. It then received an 8-episode BBC treatment in 1982, which appears to be the last attempt at bringing these characters and their times and adventures to the screen. There was also a spoof released in 1977 called The Last Remake of Beau Geste which included Peter Ustinov, James Earl Jones, and Ann-Margret among the cast, which indicates to me that the story was still well-known at that time.

My edition of the book ends with six pages of hype about the 1926 film. One note of interest to me was that a comparison of this production was made to "probably the finest picture ever produced, 'The Big Parade.'" (King Vidor-1925). This was a World War I drama that was a huge hit and is still highly regarded, and while I may have heard of the title, anything else about it has eluded my awareness up to now.

The Challenge

A rather strange and mostly obscure selection of contenders for this book.

1. Nora Roberts--Of Blood and Bone..........................................................................................658

2. Coughlin, Kuhlman & Davis--Shooter: Autobiography of the Top-Ranked Marine Sniper...246

3. Paul Theroux--The Great Railway Bazaar..............................................................................153

4. Frederic S. Durbin--A Green and Ancient Light........................................................................52

5. Alison Green--Ask a Manager...................................................................................................45

6. Rachel Manija Brown & Sherwood Smith--Stranger................................................................32

7. Russell Sullivan--Rocky Marciano: The Rock of His Times......................................................28

8. Allan Abbass--Reaching Through Resistance: Advanced Psychotherapy Techniques.............27

9. Letters Never Meant to be Read, Volume I.................................................................................19

10. Services and Prayers for the Church of England......................................................................4

11. Tia Lee--Vermilion Whispers.....................................................................................................4

12. Calameo--The History of Rome, Part I......................................................................................0

13. Alberto Vasquez-Figueroa--Tuareg...........................................................................................0

14. Joseph Jordania--Tigers, Lions and Humans.............................................................................0

15. Fiona Price--Re-Inventing Liberty..............................................................................................0

16. Samuel W. Duffield--The Latin Hymn-Writers and Their Hymns.............................................0

1st Round

#1 Roberts over #16 Duffield

No library presence for Duffield.

#2 Shooter over #15 Price

Same fate for Price

#3 Theroux over #14 Jordania

I have actually read the Theroux book some years back and even written about it on my home blog. There was a period back in the pre-Challenge days when I would read one of Theroux's travel books every summer, usually while sitting at my children's swimming lessons. I read this one, the sequel trip across Asia 30 years later in which some countries from the earlier trip had to be avoided due to political changes (while others closed off in 1974 were now open), the one going around the perimeter of England, the one about riding the train from Boston straight through to Argentina, the one making a full circuit of the Mediterranean Sea...I enjoyed all of these books.

#4 Durbin over #13 Vasquez-Figueroa

#5 Green over #12 Calameo

There is no point in advancing books that have no evident existence either in libraries or even on Amazon.

#6 Brown/Smith over #11 Lee

#7 Sullivan over #10 Services and Prayers

#8 Abbass over #9 Letters

Neither of the books in the 8-9 game are available in libraries.

Round of 8

#8 Abbass over #1 Roberts

Technically an upset, but I wouldn't have wanted to read the Roberts book anyway.

#2 Shooter over #7 Sullivan

Another upset, albeit a mild one. I don't think a sports-themed book has prevailed in the Challenge yet.

#3 Theroux over #6 Brown/Smith

#4 Durbin over #5 Green

This one was a toss-up, very little to differentiate the two contestants. I was not fired up to read either of these books.

Final Four

#2 Shooter over #8 Abbass

#3 Theroux over #4 Durbin

Championship

#2 Shooter over #3 Theroux

I would have gone with Theroux if I hadn't read it already. I probably should read something about the modern American military anyway.

Thursday, January 31, 2019

Tuesday, January 15, 2019

Author List Volume XVI

John Milton (1608-1674) Paradise Lost (1667) Born: Bread Street, City, London, England (*****9-6-96*****) Buried: St Giles Cripplegate, Fore Street, City, London, England (*****9-8-96*****) Milton's Cottage, 21 Deanway, Chalfont St Giles, Buckinghamshire, England. College: Christ's (Cambridge)

E. M. Forster (1879-1970) A Passage to India (1924) Born: 6 Melcombe Place, Dorset Square, Bloomsbury, England (*****9-1-1996*****) Buried: Ashes Scattered in rose garden, Canley Garden Cemetery and Crematorium, Coventry, Warwickshire, England. College: King's (Cambridge)

Alfred Dreyfus (1859-1935) Born: 25 Rue du Sauvage, Mulhouse, Alsace, France. Buried: Cimitiere du Montparnasse, 14eme, Paris, France. College: Ecole Polytechnique

Mary Martin (1913-1990) Born: Weatherford, Texas. Buried: Greenwood Cemetery, Weatherford, Texas.

Maude Adams (1872-1953) Born: Salt Lake City, Utah. Buried: Cemetery of the Sisters of the Cenacle, Lake Ronkonkoma, Suffolk, New York. Mountain Top Arboretum, 4 Maude Adams Road, Tannersville, Greene, New York.

John Bunyan (1628-1688) Pilgrim's Progress (1678) Born: Bunyan's End, Elstow, Bedfordshire, England. Buried: Bunhill Fields, Finsbury, London, England (*****9-8-1996*****) John Bunyan Museum, Mill Street, Bedford, Bedfordshire, England. John Bunyan Statue, The Broadway, Bedford, Bedfordshire, England. Moot Hall. Elstow, Bedfordshire, England.

Frank Norris (1870-1902) The Pit (1903) Born: Chicago, Illinois. Buried: Mountain View Cemetery, Oakland, Alameda, California. McTeague's Saloon, 1237 Polk Street, San Francisco, California. College: California (Berkeley)

Albert Camus (1913-1960) The Plague (1947) Born: Drean, Algeria. Buried: Cemetery, Lourmarin, Provence-Alpes-Cote d'Azur, France. College: Algiers

John Millington Synge (1871-1909) The Playboy of the Western World (1907) Born: 2 Newtown Villas, Rathfarnham, Dublin, Ireland. Buried: Mount Jerome Cemetery, Harold's Cross, Dublin, Ireland. Teach Synge, Inishmann, Aran Islands, Galway, Ireland. College: Trinity (Dublin)

Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) Poe's Stories (1839-45) Born: 176 Boylston Street, Boston, Massachusetts (*****8-25-2007?*****) Buried: Westminster Burial Ground, 515 West Fayette Street, Baltimore, Maryland. Edgar Allan Poe Museum, 1914 East Main Street, Richmond, Virginia. Edgar Allan Poe National Historic Site, 532 North 7th Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (*****4-25-2001?*****). Edgar Allan Poe House and Museum, 203 North Amity Street, Baltimore, Maryland. Edgar Allan Poe Cottage, 2640 Grand Concourse, Fordham, Bronx, New York. College: Virginia; Army.

Dubose Heyward (1885-1940) Porgy (1925) Born: Charleston, South Carolina. Buried: St Philip's Episcopal Church Cemetery, Charleston, South Carolina. Cabbage Row, 89-91 Church Street, Charleston, South Carolina.

George Gershwin (1898-1937) Born: 242 Snediker Avenue, Brooklyn, Kings, New York. Buried: Westchester Hills Cemetery, Hastings-on-Hudson, Westchester, New York.

Robert Nathan (1894-1985) Portrait of Jenny (1940) Born: New York, New York. Buried: Westwood Memorial Park, Los Angeles, California. College: Harvard.

James Joyce (1882-1941) A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916), Ulysses (1922) Born: 41 Brighton Square, Rathgar, Dublin, Ireland (*****9-3-1996*****) Buried: Fluntern Cemetery, Zurich, Switzerland. James Joyce Tower & Museum, Sandycove Point, Dun Laoghaire, Dublin, Ireland. (*****9-4-1996*****) James Joyce Center, 35 North Great George's Street, Rotunda, Dublin, Ireland. James Joyce Statue, North Earl Street, Dublin, Ireland (*****9-4-1996*****) James Joyce Pub, Pelikanstrasse 8, Zurich, Switzerland. College: University (Dublin).

Leon Feuchtwanger (1884-1958) Power (1926) Born: Munich, Bavaria, Germany. Buried: Woodlawn Cemetery, Santa Monica, Los Angeles, California. College: Munich; Berlin.

Josephus (37-100) Born: Jerusalem, Israel.

Niccolo Machiavelli (1469-1527) The Prince (1532) Born: Florence, Tuscany, Italy. Buried: Basilica di Santa Croce, Florence, Tuscany, Italy. Casa di Machiavelli, via Scopeti, San Casciano in Val di Pesa, Tuscany, Italy.

W. K.Barrett (1847-1927) Born: Colston Bassett, Nottinghamshire, England.

Edward VI (1537-1553) Born: Hampton Court Palace, Richmond, Middlesex, London, England. Buried: Westminster Abbey, Westminster, London, England.

Anthony Hope (1863-1933) The Prisoner of Zenda (1894) Born: Clapton, Hackney, London, England. Buried: St Mary and St Nicholas Churchyard, Leatherhead, Surrey, England.

College: Balliol (Oxford)

Thursday, January 10, 2019

January 2019

A List: Cardinal Newman--Apologia Pro Vita Sua......................................198/430

B List: Percival Christopher Wren--Beau Geste..........................................248/418

C List: Toni Morrison--The Bluest Eye..........................................................56/216

This is my second Cardinal Newman book. I think that, other than Carlyle, he is the celebrated Victorian writer whose work translates least well to the mentality of our present age. The problem is no doubt as much with me as it is with him. I was expecting a "spiritual biography" in either the ancient or more modern sense of the writer struggling with his sinful or unbelieving nature and encountering God and his Works at a very intense and intimate level. I was not expecting rather in-depth accounts of theological disputes among once prominent but now largely obscure clergymen and scholars stretched out over the course of decades, which is what constitutes the bulk the Apologia to this point. Foolish me. Newman was a serious man, or at least he took his avocation deadly seriously. However the questions that were all-consuming to him are not ones that I care very much about.

One wonders what Newman would think if he could see his old Oxford today.

I will do a longer report on Beau Geste of course when it is finished. I will say that, whatever its defects as literary art, it has a quality of fun and high-spiritedness about it that I like a great deal, and one that is pretty rare. One of the reasons I like the IWE list is that it does seem to have a higher percentage of books of this character than other good-for-you kinds of lists do.

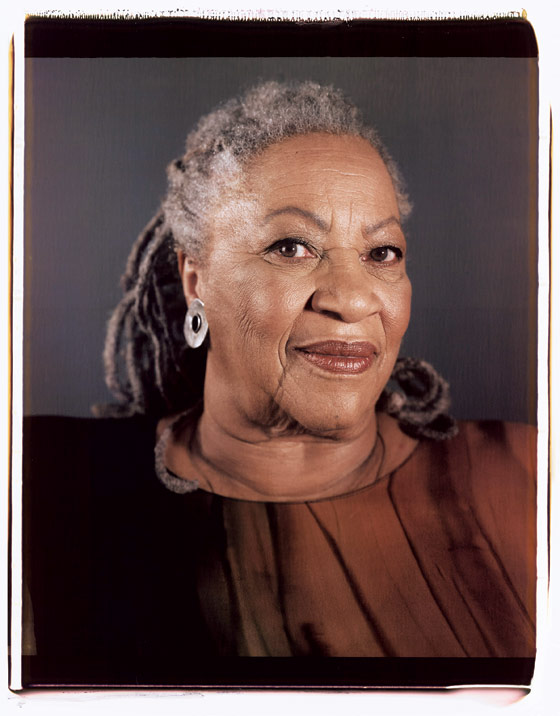

Toni Morrison, whom I have not read before, is one of those writers who seems to have both more extreme supporters and detractors, and to come with more restrictive critical boundaries as far as what is considered acceptable to say about her, and even the tone in which to say it, depending on who you are, or who you think you are, than is usual, which is somewhat unfortunate. This is her first book, and my impression is that it is the most conventional and least disturbing of her works. The style is (to me) not far off from the careful, tight minimalism that was in vogue around that time, and is a good example of it. It is perhaps inevitably to someone from my perspective a sad book, because the lives in it are largely unrelieved by anything that I would find appealing, but I will say that every sentence in it thus far has a certain weight and holds my interest and attention, which is a noteworthy occurrence.

B List: Percival Christopher Wren--Beau Geste..........................................248/418

C List: Toni Morrison--The Bluest Eye..........................................................56/216

This is my second Cardinal Newman book. I think that, other than Carlyle, he is the celebrated Victorian writer whose work translates least well to the mentality of our present age. The problem is no doubt as much with me as it is with him. I was expecting a "spiritual biography" in either the ancient or more modern sense of the writer struggling with his sinful or unbelieving nature and encountering God and his Works at a very intense and intimate level. I was not expecting rather in-depth accounts of theological disputes among once prominent but now largely obscure clergymen and scholars stretched out over the course of decades, which is what constitutes the bulk the Apologia to this point. Foolish me. Newman was a serious man, or at least he took his avocation deadly seriously. However the questions that were all-consuming to him are not ones that I care very much about.

One wonders what Newman would think if he could see his old Oxford today.

I will do a longer report on Beau Geste of course when it is finished. I will say that, whatever its defects as literary art, it has a quality of fun and high-spiritedness about it that I like a great deal, and one that is pretty rare. One of the reasons I like the IWE list is that it does seem to have a higher percentage of books of this character than other good-for-you kinds of lists do.

Toni Morrison, whom I have not read before, is one of those writers who seems to have both more extreme supporters and detractors, and to come with more restrictive critical boundaries as far as what is considered acceptable to say about her, and even the tone in which to say it, depending on who you are, or who you think you are, than is usual, which is somewhat unfortunate. This is her first book, and my impression is that it is the most conventional and least disturbing of her works. The style is (to me) not far off from the careful, tight minimalism that was in vogue around that time, and is a good example of it. It is perhaps inevitably to someone from my perspective a sad book, because the lives in it are largely unrelieved by anything that I would find appealing, but I will say that every sentence in it thus far has a certain weight and holds my interest and attention, which is a noteworthy occurrence.

Tuesday, January 1, 2019

Anthony Trollope--Barsetshire Chronicles: The Warden (1855) and Barchester Towers (1857)

Somehow in the course of my more than three decade reading career I had never happened to read anything by Trollope, the favorite Victorian novelist of mildly sardonic middle-aged men throughout the English-speaking world, until now. Of these first two entries in the Barsetshire series, the IWE introduction states that "together they are considered the best work Trollope did." Conventional wisdom seems to further consider Barchester Towers to be the superior of the two, and it is more than twice as long and has naturally many of the same agreeable qualities as its predecessor. However I found that it ran out of steam somewhat in the last one hundred pages, something Trollope himself took two pages out of the narrative to lament at the beginning of Chapter LI:

"These leave-takings in novels are as disagreeable as they are in real life...Promises of two children and superhuman happiness are of no avail, nor assurance of extreme respectability carried to an age far exceeding that usually allotted to mortals...Do I not myself know that I am at this moment in want of a dozen pages, and that I am sick with cudgeling my brains to find them?"

The Warden, in contrast, coming in at just under 200 pages, struck me as a nearly perfectly executed novel. It is humorous and has numerous contrasting and interesting characters, an unusual plot full of constant unexpected twists and ironic turns right up to the very last page. Barchester Towers continues in the same vein for at least its first half, after which it falters somewhat in inventiveness and energy, and becomes on the whole a much more conventional book.

The IWE somewhat oddly singled out Mr. Harding, the 'warden' of the first volume, as "an excellent creation." While a more prominent and rounded character in The Warden than it its sequel, this character's role is really that of the ordinary retiring sort of man who wants to be comfortable and avoid conflict in his life contrasted against a gallery of much more strident and combative personalities. The imperious Dr. Grantly was my personal favorite character, and numerous of the other personages with highly developed egos possessed qualities that contributed to the general merriment of the books (as will be seen in the extensive excerpts below) in a way that Mr. Harding did not.

From the introduction to the Modern Library edition, written by A. Edward Newton of 501 N 19th Street in Philadelphia, the founder of the Trollope Society, on March 1, 1936:

"Men of my age do not laugh much or heartily...they have seen and known too much of the world."

I cannot find now, if it is to be found, the exact age of Mr. A. Edward Newton when he wrote this essay. He does not appear to be less than fifty years of age at least, however. As noted elsewhere the claim made in the quote above is not infrequent among Trollope's contemporary admirers. I myself do not laugh so much, though comparatively I have not seen so much of the world, and seem to know even less. I still like the books, however.

The Warden, Chap. III:

"The bishop did not whistle: we believe that they lose the power of doing so on being consecrated; and that in these days one might as easily meet a corrupt judge as a whistling bishop..."

Looks like Mr. Harding and Eleanor

Chap. V

"Many a man can fight his battle with good courage, but with a doubting conscience. Such was not the case with Dr. Grantly. He did not believe in the Gospel with more assurance than he did in the sacred justice of all ecclesiastical revenues."

Examples of the strain of humor to be found throughout this book.

Chap. VI

"...and Mrs. Goodenough, the red-faced rector's wife, pressing the warden's hand, declared she had never enjoyed herself better; which showed how little pleasure she allowed herself in this world, as she had sat the whole evening through in the same chair without occupation, not speaking, and unspoken to."

Chap. VII

"They say that faint heart never won fair lady; and it is amazing to me how fair ladies are won, so faint are often men's hearts!"

This is England (a romantic country).

Article in the influential newspaper The Jupiter:

"We must express an opinion that nowhere but in the Church of England, and only there among its priests, could such a state of moral indifference be found."

This prompted me to note at this point that "This book is too funny."

Chap. XVIII

"A clergyman generally dislikes to be met in argument by any scriptural quotation; he feels as affronted as a doctor does, when recommended by an old woman to take some favourite dose, or as a lawyer when an unprofessional man attempts to put him down by a quibble."

Mr. Popular Sentiment is a pretty good spoof on Dickens.

Chap. XIX

"If you owe me nothing', and the archdeacon looked as though he thought a great deal were due to him, 'at least you owe so much to my father."

Chap. XX

"And here we must take leave of Archdeacon Grantly. We fear that he is represented in these pages as being worse than he is; but we have had to do with his foibles, and not with his virtues."

Now into the Barchester Towers Chapter II:

"Some few years since, even within the memory of many who are not yet willing to call themselves old, a liberal clergymen was a person not frequently to be met. Sydney Smith was such, and was looked on as little better than an infidel."

Chap. III

"Mrs. Proudie determined that her husband's equipage should not shame her, and things on which Mrs. Proudie resolved, were generally accomplished."

This is the first hit in a search for "anthony trollope sexy"

"It is not my intention to breathe a word against the character of Mrs. Proudie, but still I cannot think that with all her virtues she adds much to her husband's happiness...All hope of defending himself has passed from him; indeed he rarely even attempts self-justification; and is aware that submission produces the nearest approach to peace which his own house can ever attain."

Chap. VI

"There is, perhaps, no greater hardship at present inflicted on mankind in civilised and free countries, than the necessity of listening to sermons...Let a professor of law or physic find his place in a lecture-room and there pour forth jejune words and useless empty phrases and he will pour them forth to empty benches...A member of Parliament can be coughed down or counted out...But no one can rid himself of the preaching clergyman."

Chap. VII

"Doubting himself was Mr. Harding's weakness. It is not, however, the usual fault of his order."

All of these snippets are things I laughed at within the context of the story. I found this book entertaining and a welcome addition to the universe of the Victorian English novel such as it is constructed in my mind, but I do not have very much to say about it.

"Among these Mr. Quiverful, the rector of Puddingdale, whose wife still continued to present him from year to year with fresh pledges of her love, and so to increase his cares and, it is to be hoped, his happiness equally."

Mr. Quiverful had fourteen children. He belonged to that category of men who was overwhelmed by the results of his fecundity rather than a forceful director of it.

Chap. IX

"The Stanhopes would visit you in your sickness (provided it were not contagious), would bring you oranges, French novels, and the last new bit of scandal, and then hear of your death or your recovery with an equally indifferent composure."

I sometimes wonder whether my own children aren't going the way of the Stanhopes in some areas.

Chap. X

"He felt that if he intended to disapprove, it must be now or never; but he also felt that it could not be now."

Chap. XI

"German professors!' groaned out the chancellor, as though his nervous system had received a shock which nothing but a week of Oxford air could cure."

"I was a Jew once myself', began Bertie."

I laughed for five minutes at this line.

Chap. XIII Too fitting for me to let pass by.

"A man is sufficiently condemned if it can only be shown that either in politics or religion he does not belong to some new school established within the last score of years. He may then regard himself as rubbish and expect to be carted away. A man is nothing now unless he has within him a full appreciation of the new era; an era in which it would seem that neither honesty nor truth is very desirable, but in which success is the only touchstone of merit. We must laugh at everything that is established."

"It is very easy to talk of repentance; but a man has to walk over hot ploughshares before he can complete it; to be skinned alive as was St. Bartholomew; to be stuck full of arrows as was St. Sebastian; to lie broiling on a gridiron like St. Lorenzo!"

Chap XIV This is my favorite passage/quote in the whole book.

"Mr. Harding did not like being called lily-livered, and was rather inclined to resent it. 'I doubt there is any true courage,' said he, 'in squabbling for money." "If honest men did not squabble for money, in this wicked world of ours, the dishonest men would get it all; and I do not see that the cause of virtue would be much improved."

Chap. XIX

"They habitually looked on the sunny side of the wall, if there was a gleam on either side for them to look at; and, if there was none, they endured the shade with an indifference which, if not stoical, answered the end at which the Stoics aimed."

Chap. XXX (trying to move things along a little)

"How easily would she have forgiven and forgotten the archdeacon's suspicions had she but heard the whole truth from Mr. Arabin. But then where would have been my novel?"

Chap. XXXIII

"In truth, Mrs. Proudie was all but invincible; had she married Petruchio, it may be doubted whether that arch wife-tamer would have been able to keep her legs out of those garments which are presumed by men to be peculiarly unfitted for feminine use."

Chap. XXXV

"The quality, as the upper classes in rural districts are designated by the lower with so much true discrimination, were to eat a breakfast, and the non-quality were to eat a dinner...a subsidiary board was to be spread sub dio for the accommodation of the lower class of yokels..."

Chap. XXXVII

"Wise people, when they are in the wrong, always put themselves right by finding fault with the people against whom they have sinned. Lady De Courcy was a wise woman; and therefore, having treated Miss Thorne very badly by staying away till three o'clock, she assumed the offensive and attacked Mr. Thorne's roads."

Chap. XLIII

"People when they get their income doubled usually think that those through whose instrumentality this little ceremony is performed are right at bottom."

All right, that is enough. Thanks for the memories, Trollope. You don't appear again on the IWE list and the GRE test book seems to ignore you altogether, so it is possible our paths will never cross again, though I hope that by some mechanism they shall.

The Bourgeois Surrender Challenge

Some very weird entries in this Challenge.

1. Jennifer Nielsen--A Night Divided...........................................................245

2. Daniel Pool--What Jane Austen Ate and Charles Dickens Knew............163

3. Robert Gates--A Passion For Leadership................................................136

4. F. Scott Fitzgerald--Short Stories...............................................................68

5. Fyodor Dostoevsky--The Possessed...........................................................56

6. Anthony Trollope--The Last Chronicle of Dorset......................................39

7. Eugene Pogany--In My Brother's Image....................................................30

8. Mary Elizabeth Braddon--Run to Earth......................................................14

9. Will Self--Shark..........................................................................................11

10. The Whole Family: A Novel by Twelve Authors.........................................7

11. Ireland & the British Empire (ed. Kenny)..................................................2

12. The Trollope Critics (ed. Hall)....................................................................1

13. Dr Heinrich Graetze--Influence of Judaism on the Protestant Reformation.0

14. Walter Besant--London...............................................................................0

15. James Peebles--Compulsory Vaccination: A Menace to Personal Liberty..0

16. John Keefe--Exploring Careers in the Sun Belt...........................................0

17. R. D. McMaster--Trollope & the Law..........................................................0

18. Harold Bloom--The Victorian Novel............................................................0

Qualifying Round

#18 Bloom over #15 Peebles

The Peebles book, though doubtless spectacular, is not in wide circulation.

#16 Keefe over #17 McMaster

The unavailability of either book and the lackluster interest I have in McMaster's subject matter allows the higher seed to advance here. \

Round of 16

#1 Nielsen over #18 Bloom

Nielsen is a children's book about the Berlin Wall. I changed my mind after initially giving Bloom a close victory.

#2 Pool over #16 Keefe

#3 Gates over #14 Besant

No library representation for Besant.

#4 Fitzgerald over #13 Graetze

#5 Dostoevsky over #12 The Trollope Critics

#6 Trollope over #11 Ireland and the British Empire

#7 Pogany over #10 The Whole Family

#9 Self over #8 Braddon

Final 8

#9 Self over #1 Nielsen

#2 Pool over #7 Pogany

Pogany is a lot shorter, but it isn't available at my library and it's a Holocaust-themed book. I wimped out on it at the last minute.

#6 Trollope over #3 Gates

#4 Fitzgerald over #5 Dostoevsky

My particular mood at the time of the match, nothing more. Fitzgerald has appeared several times in the tournament without winning.

Final 4

#9 Self over #2 Pool

While the Pool deserves a run, it doesn't deserve a run all the way to the final.

#4 Fitzgerald over #6 Trollope

I didn't want to read the 6th and final book of the Barsetshire Chronicles without having read #s 3, 4 and 5 if I can help it.

Championship

#9 Self over #4 Fitzgerald

Self is a contemporary writer of some repute. A specific edition of Fitzgerald's stories was not denoted for the competition, a complete collection runs upwards of 700 pages, and I often have occasion to read some of his stories in my other systems, so I am going to give the Self book a try.

Thursday, December 6, 2018

December 2018

A List: Shakespeare--Richard II............................................................5/32

B List: Trollope--Barsetshire Chronicles: Barchester Towers.......597/746

C List: Bill Bryson--I'm a Stranger Here Myself..............................14/288

Richard II is the 3rd of a run of Shakespeare plays--the other 2 being Henry VI Part 1 and Troilus and Cressida--that had not managed to come up on the A list yet. I have recorded somewhere how many of the Shakespeare plays I have read at one time or another--some of the lesser known ones that I have only read once I have trouble remembering whether I have or not--but I got very busy this week, one of my cars had to go into the shop, etc, so I didn't get around to looking up how many of them I have marked down. I think around 2/3rds of the 37, or is it 38? As with most things, even great ones, I have periods in my life where the greatness of Shakespeare reveals itself more readily and is more important to my daily life and the firing of my imaginative faculties than it is at other times. I am not in one of those special times currently. I hope I have a couple more such epochs left in me.

I am probably in close to the ideal frame of mind for taking on Trollope, but I will expand on this in the big essay that I'll do when I finish the book.

Obviously I have just started the Bryson book, which was published in 1999 and seems to be a series of humorous vignettes around his return to the United States (actually Hanover, New Hampshire, which is a fine town but about as unrepresentative of the real United States as you can get) after 20 years abroad. Some of my impressions 14 pages in are as follows:

1. Though the book is less than 20 years old the world depicted in it is so dated as to be almost comical. We've already been treated to five pages on the wonders of the postal service, and a letter from England that made it to his house despite being addressed merely "New Hampshire, somewhere in America". Then there was a reminiscence about coming home from the pub in England and watching 90 minute science programs on television before going to bed. Basically this looks like it is going to be chock full of activities, jobs, cultural habits, that died within about five years of this book's publication.

2. It is unbelievable that within living memory--heck, my own early adulthood--people could apparently make upper middle class incomes writing, well, I don't know, stuff like what I've just described, and have fabulous overall careers. This guy Bryson in his heyday sold voluminous numbers of books (5.9 million in the 2000s alone!), made many TV appearances, gave lecture tours, was the chancellor of Durham University. I know people will say a person like me has no idea how difficult it is to be a professional writer who has to turn out regular work on a deadline and how serious this is and all right, fine. Even so, this guy has to get up every day and think, whew, I lucked out in the timing of my career. But maybe he doesn't.

3. I feel like this "I left America for x number of years and boy did things change a lot" theme was a popular one in the late 90s that has kind of gone away. Does anybody at the educated level of society really leave anywhere and not return for years on end anymore? Is it really possible to "get away" the way it used to be in the modern overconnected world?

...I too am on a deadline for this one monthly post and my time is up now.

This guy will not be stopped.

B List: Trollope--Barsetshire Chronicles: Barchester Towers.......597/746

C List: Bill Bryson--I'm a Stranger Here Myself..............................14/288

Richard II is the 3rd of a run of Shakespeare plays--the other 2 being Henry VI Part 1 and Troilus and Cressida--that had not managed to come up on the A list yet. I have recorded somewhere how many of the Shakespeare plays I have read at one time or another--some of the lesser known ones that I have only read once I have trouble remembering whether I have or not--but I got very busy this week, one of my cars had to go into the shop, etc, so I didn't get around to looking up how many of them I have marked down. I think around 2/3rds of the 37, or is it 38? As with most things, even great ones, I have periods in my life where the greatness of Shakespeare reveals itself more readily and is more important to my daily life and the firing of my imaginative faculties than it is at other times. I am not in one of those special times currently. I hope I have a couple more such epochs left in me.

I am probably in close to the ideal frame of mind for taking on Trollope, but I will expand on this in the big essay that I'll do when I finish the book.

Obviously I have just started the Bryson book, which was published in 1999 and seems to be a series of humorous vignettes around his return to the United States (actually Hanover, New Hampshire, which is a fine town but about as unrepresentative of the real United States as you can get) after 20 years abroad. Some of my impressions 14 pages in are as follows:

1. Though the book is less than 20 years old the world depicted in it is so dated as to be almost comical. We've already been treated to five pages on the wonders of the postal service, and a letter from England that made it to his house despite being addressed merely "New Hampshire, somewhere in America". Then there was a reminiscence about coming home from the pub in England and watching 90 minute science programs on television before going to bed. Basically this looks like it is going to be chock full of activities, jobs, cultural habits, that died within about five years of this book's publication.

2. It is unbelievable that within living memory--heck, my own early adulthood--people could apparently make upper middle class incomes writing, well, I don't know, stuff like what I've just described, and have fabulous overall careers. This guy Bryson in his heyday sold voluminous numbers of books (5.9 million in the 2000s alone!), made many TV appearances, gave lecture tours, was the chancellor of Durham University. I know people will say a person like me has no idea how difficult it is to be a professional writer who has to turn out regular work on a deadline and how serious this is and all right, fine. Even so, this guy has to get up every day and think, whew, I lucked out in the timing of my career. But maybe he doesn't.

3. I feel like this "I left America for x number of years and boy did things change a lot" theme was a popular one in the late 90s that has kind of gone away. Does anybody at the educated level of society really leave anywhere and not return for years on end anymore? Is it really possible to "get away" the way it used to be in the modern overconnected world?

...I too am on a deadline for this one monthly post and my time is up now.

This guy will not be stopped.

Wednesday, November 7, 2018

November 2018

A List: James Russell Lowell--A Fable For Critics..........................................66/95

B List: Anthony Trollope--Barsetshire Chronicles (Barchester Towers)......273/746

C List: Lucy Lethbridge--Servants: A Downstairs View of 20th Cent, etc....216/325

The weather turned chilly early this year. My last real day of reading on the porch was October 10th, when it was 80 degrees. The next day it dropped down to the low 60s and poured rain. I tried to go out but gave it up after about 10 minutes and came back in. After that it dropped into the lower 50s and 40s and has stayed there ever since. I'll probably be inside now until May.

The James Russell Lowell work here is a bit of 19th century doggerel verse that I am reading online, because even the state library doesn't have a printed copy of it that circulates. It is something of a humorous overview of the American--really the New England literary and cultural scene, with a few New Yorkers such as Cooper included, circa 1850. I am reading it because some of the lines on Emerson were excerpted for one of the exam questions in the GRE book I get this list from.

Barchester Towers is the second volume of the Barsetshire Chronicles. I have already dusted off The Warden, which clocks in at a trim 199 pages. There are six novels in the series altogether, but the IWE list only features and summarizes the first two. These first two novels were also published together in a single Modern Library edition, with no accompanying books containing any of the other four. So I think I am only going to read the first two as well, especially seeing as these make for a long enough book anyway. They are very good though. I find myself often regretting that I have to stop for the day and can't go on because I want to see what happens next, which is something that rarely occurs with me anymore, even when I generally like what I'm reading. But this is my first time ever reading Trollope, so he is both new to me and the kind of writer I am inclined to like, which I guess is a combination I don't encounter that often anymore.

The Lucy Lethbridge book, a survey of the British servant experience and the decline of that way of life over the past century, feels a little padded at times but contains some matters of interest to me. I always like it when the time for some activity or social arrangement has passed, but there are still people trying to carry on the old forms onto the point of ridiculousness, such as the dowager in the late 1930s who requires a staff of 8 people to pull together a glass of Benger's (Ovaltine-like drink) and two slices of toast and bring it to her room on a silver tray. I had not been aware that many of the great country houses of England did not get electricity or in some cases even modern bathrooms until well into the 30s (the chamberpot long remained the outlet of choice, it seems). I also had not known about the extreme preference for height when footmen, serving maids and other visible help. There was one lord who required all the women on his staff to be at least five foot ten, and he employed around thirty of them. I would not have thought there would be so much height to go around.

The author, Lucy Lethbridge, indicates in the dedication that one of her grandmothers at least was in service. I've been digging around the internet for pictures of her when she was younger, even at age 40. The only ones I can find are from when her book came out, at which time she was around fifty, but she gives one the idea that she was probably a looker, to somebody like me anyway, in her younger years. The combination of lingering working class earthy sensuality with such evidences of a decent education as can be presumed would decidedly hit my sweet spots. But I suppose we'll never know.

Near the head of my long, long list of romantic regrets is never having had any kind of relations with a real English girl. I mean even a few words over a drink. I don't know that I've ever even talked to one. That's how elusive they are to the likes of me.

This is the actress who plays one of the Stanhope daughters in the BBC Adaptation of 'Barchester Towers'. I just left off today at the chapter where the Reverend Stanhope was recalled to his parish by the new bishop after spending 13 years in Italy so I have not encountered these characters yet. Apparently their role is not a minor one.

B List: Anthony Trollope--Barsetshire Chronicles (Barchester Towers)......273/746

C List: Lucy Lethbridge--Servants: A Downstairs View of 20th Cent, etc....216/325

The weather turned chilly early this year. My last real day of reading on the porch was October 10th, when it was 80 degrees. The next day it dropped down to the low 60s and poured rain. I tried to go out but gave it up after about 10 minutes and came back in. After that it dropped into the lower 50s and 40s and has stayed there ever since. I'll probably be inside now until May.

The James Russell Lowell work here is a bit of 19th century doggerel verse that I am reading online, because even the state library doesn't have a printed copy of it that circulates. It is something of a humorous overview of the American--really the New England literary and cultural scene, with a few New Yorkers such as Cooper included, circa 1850. I am reading it because some of the lines on Emerson were excerpted for one of the exam questions in the GRE book I get this list from.

Barchester Towers is the second volume of the Barsetshire Chronicles. I have already dusted off The Warden, which clocks in at a trim 199 pages. There are six novels in the series altogether, but the IWE list only features and summarizes the first two. These first two novels were also published together in a single Modern Library edition, with no accompanying books containing any of the other four. So I think I am only going to read the first two as well, especially seeing as these make for a long enough book anyway. They are very good though. I find myself often regretting that I have to stop for the day and can't go on because I want to see what happens next, which is something that rarely occurs with me anymore, even when I generally like what I'm reading. But this is my first time ever reading Trollope, so he is both new to me and the kind of writer I am inclined to like, which I guess is a combination I don't encounter that often anymore.

The Lucy Lethbridge book, a survey of the British servant experience and the decline of that way of life over the past century, feels a little padded at times but contains some matters of interest to me. I always like it when the time for some activity or social arrangement has passed, but there are still people trying to carry on the old forms onto the point of ridiculousness, such as the dowager in the late 1930s who requires a staff of 8 people to pull together a glass of Benger's (Ovaltine-like drink) and two slices of toast and bring it to her room on a silver tray. I had not been aware that many of the great country houses of England did not get electricity or in some cases even modern bathrooms until well into the 30s (the chamberpot long remained the outlet of choice, it seems). I also had not known about the extreme preference for height when footmen, serving maids and other visible help. There was one lord who required all the women on his staff to be at least five foot ten, and he employed around thirty of them. I would not have thought there would be so much height to go around.

The author, Lucy Lethbridge, indicates in the dedication that one of her grandmothers at least was in service. I've been digging around the internet for pictures of her when she was younger, even at age 40. The only ones I can find are from when her book came out, at which time she was around fifty, but she gives one the idea that she was probably a looker, to somebody like me anyway, in her younger years. The combination of lingering working class earthy sensuality with such evidences of a decent education as can be presumed would decidedly hit my sweet spots. But I suppose we'll never know.

Near the head of my long, long list of romantic regrets is never having had any kind of relations with a real English girl. I mean even a few words over a drink. I don't know that I've ever even talked to one. That's how elusive they are to the likes of me.

This is the actress who plays one of the Stanhope daughters in the BBC Adaptation of 'Barchester Towers'. I just left off today at the chapter where the Reverend Stanhope was recalled to his parish by the new bishop after spending 13 years in Italy so I have not encountered these characters yet. Apparently their role is not a minor one.

Monday, October 15, 2018

Ellen Glasgow--Barren Ground (1925)

"Ellen Glasgow's reputation" says the IWE introduction, "was already good and her novels many, but the publication of Barren Ground in 1926 (?) was what chiefly made it clear that she was a major novelist. Mrs Glasgow wrote not about her own upper-class circles--though later she proved she could do so with equal success--but about the rural people of the countryside near her native Richmond, Virginia. Like fine poetry or music Barren Ground in its writing reflects the temperament of the action depicted, dull or emotional or brisk as the case may be." The "Note on the Author" in the circa 1936 Modern Library edition I had is somewhat more pointed and colorful:

"The proud South at first resented and then acclaimed one of its aristocratic daughters for her revolt against the sentimental tradition of her environment. Born in Richmond, Virginia, Ellen Glasgow had all the advantages of education and leisure of the privileged. After taking her degree and winning a Phi Beta Kappa key at the University of Virginia, Miss Glasgow began her career as an author with the publication of an anonymous novel in 1897. In open defiance of the genteel prejudice against women expressing themselves on such controversial subjects as politics, Miss Glasgow staked her reputation and social position on a novel published under her own name. The Voice of the People was an instantaneous success. Since its appearance one novel has followed another and Miss Glasgow's reputation has grown steadily. Today she ranks as one of the leading women novelists of the country..."

I don't know why the IWE refers to her as "Mrs" while the Modern Library uses "Miss".

Taking into consideration her former status, what I perceive to be the general desire for female writers of the past to be more appreciated, and the circumstance that Barren Ground at least is a book of considerable literary quality that even apart from having a quite empowered heroine for its time offers much of value to the national literary landscape, it is perhaps surprising that Ellen Glasgow is not more remembered. I suspect her handling of race, while not overtly mean-spirited or to me obtrusively offensive given her generation and the atmosphere in which she lived, is not adequate to the requirements of our era. Her overall attitude in this area struck me as having some similarity to Faulkner's (which I hear criticized as well), but of course without his subtlety and force to mitigate some of the more obvious objections to be made. This subject will inevitably come up several times during this report.

Remarkably, I cannot recall ever having read a novel set in Virginia before this, which especially stands out to me because I have lived in that state (though it is my least favorite place that I have lived). I suppose I have read some D.C.-set books where one of the characters lived in Arlington or worked at the Pentagon or a Civil War book where some of the camp or battle scenes took place there, but this is the first I can think of with a domestic setting, extensive description of nature and seasons and local society over a period of many years and so forth. I took a lot of notes on it.

p.5 "...the greater number arrived, as they remained, 'good people,' a comprehensive term, which implies, to Virginians, the exact opposite of the phrase, 'a good family.' The good families of the state have preserved, among other things, custom, history, tradition, romantic fiction, and the Episcopal Church. The good people, according to the records of clergymen, which are the only surviving records, have preserved nothing except themselves."

(Early on) This book is part "The Waltons", part As the Earth Turns, with a hint of Faulkner.

Sexuality in old books is (generally speaking) normal. Conventional love affairs, etc, of a brief duration in which the intensity is even more vanishingly fleeting. Instances of women being highly promiscuous, incest, etc, are understood, or at least presumed, to be unusual. Less anxiety for bourgeois readers, which perhaps they need once in a while.

p.43 "Mrs Oakley looked down on the 'poor white' class, though she had married into it...He had made her a good husband; it was not his fault that he could never get on; everything from the start had been against him; and he had always done the best that he could." I hope my wife doesn't read this passage, lest some truths hit too close to home.

p. 81 "Until yesterday Dorinda had regarded the monotonous routine of the store as one of the dreary, though doubtless beneficial, designs of an inscrutable Providence." That "though doubtless beneficial" is a good piece of characterization.

The use of black dialect throughout here is probably such as to be offensive. Glasgow is not a comic writer, so she is going for realism, not humor. I have seen it done worse, but perhaps we don't need quite so much of it to make the point. On the other hand, is there no value in her having made some record of it? Assuming it is accurate. One presumes that she lived among people like these characters, and that their speech was distinct from that common among the whites, and also she was a conscientious writer of well above average literary skill, so "accuracy" insofar as she is presenting her own interpretation of what she heard, does not seem to me to be problematic and would certainly be in accord with literary custom.

Like many older books, this took around 100 pages to get going. My sense is that consensus opinion today holds that that is too long even for supposedly great books and demands way too much of a person's time to be worthwhile in the modern world. I would dispute that of course, because I like what I take to be the expansive effects of leisurely book-reading on my own mind mostly, though I don't think the trend of even smarter younger people moving away from this practice is really benefiting their cognitive development. Such knowledge as they acquire seems to me to be confined with narrower channels into which more reading perhaps would have allowed more air and a more comprehensive vision.

Old books have two main kinds of pregnancy dilemmas. Either the boy is too low status to avoid a forced marriage/have the problem taken care of, or he is too high status to be forced into marriage (from the girl's point of view). We have the second type of that sad story here.

p. 274 "She wished he wouldn't say 'ni**ers.' That scornful label was already archaic, except among the poorest of the 'poor white class' at Pedlar's Mill." This is somewhat progressive, I suppose, but then a few pages later (281-2) there is the somewhat ubiquitous white author denial/avoidance/whitewashing passage that has become mostly inexcusable in our days:

"Like her mother, she was endowed with an intuitive understanding of the negroes; she would always know how to keep on friendly terms with that immature but not ungenerous race. Slavery in Queen Elizabeth County had rested more lightly than elsewhere...It was true that the coloured people about Pedlar's Mill were as industrious and as prosperous as any in the South, and that, within what their white neighbours called reasonable bounds, there was, at the end of the nineteenth century, little prejudice against them...As for the negroes themselves, they lived contentedly enough as inferiors though not dependents."

My copy, alas, did not have this groovy dust jacket.

p. 324 "Mrs. Oakley was a pious and God-fearing woman, whose daily life was lived beneath the ominous shadow of the wrath to come; yet she had deliberately perjured herself in order that a worthless boy might escape the punishment which she knew he deserved." It is my observation that women authors are much more likely, if not to directly refer to certain male characters in such withering terms as "worthless", "inferior", "cowardly", etc, to develop them at greater length and detail before passing down these oracular judgments, which I find gives them a certain sting whose impression lasts longer than the introduction of such characters in male authors, whose purpose more frequently is merely to give the hero someone to defeat or otherwise display his own overwhelming superiority in contrast with, and whose existence or behavior is otherwise of little significance.

p. 326 "The Lord helps good sleepers." I hope so.

p. 365 "She had seen enough of the world to know that you took your husband...where you found him, and she was troubled by few illusions about marriage."

p. 371 "That, she had learned, was the hidden sting of success; it rubbed old sores with the salt of regret until they were raw again."

p. 372 "Yes, that's the trouble about getting comforts. We always remember that other people went without them. I've got the carpets now that Rose Emily wanted." I like this last quote, there seems to me to be something in it. The two previous I am not as convinced of, but in the context of the book I thought what it revealed about its character's point of view was interesting.

p. 443 "It had never seemed possible to her that Nathan could die. He had not mattered enough for that." This is the main character's husband, whom she married at a rather mature age, 38 or so. It is implied in the book that sexual consummation in this marriage was never achieved. The character, Dorinda, had given herself to a lover at age 20 and been jilted, and the plot of the book is essentially the long grind through the rest of her life to renounce passion and love overcome this setback and the exhausted, narrow life of her rural community to become successful and gain a measure of revenge on her onetime lover, who eventually descends into alcoholism and poverty. This aspect of a woman who determines to get along without dependence on or emotional connection to males or to be weighed down by children was actually rather timely given the recent outpouring of female anger and disgust with much of masculine society that has become so prominent in the culture.

p. 511 "I've seen so many people die," she thought, and then, "In fifty years many people must die." I only note this because this is the point of life that I am at now.

p. 521 "Youth can never know the worst, she understood, because the worst that one can know is the end of expectancy."

Dorinda's struggle with love, both getting over the jilting of her early life and her refusal to engage with it at all in the remainder of the book, I thought was too much. Several times the reader is assured that she has overcome any bitterness or desire for it that she may have had once and for all, but the supposedly suppressed feelings seem to be aroused too easily and too often for this to be wholly credible.

The Bourgeois Surrender Challenge

1. Toni Morrison--The Bluest Eye......................................................1,234

2. William James--The Varieties of Religious Experience....................311

3. Taxi (movie--2004)............................................................................289

4. Winston Graham--Poldark: The Black Moon....................................279

5. D. C. Cab (movie)..............................................................................165

6. Eric Weiner--The Geography of Genius............................................158

7. A.P.J. Abdul Kalam--Wings of Fire..................................................114

8. J.L. Langley--The Tin Star.................................................................109

9. Nathaniel Hawthorne--The Blithedale Romance.................................58

10. Rebecca Morris--A Murder in My Hometown...................................38

11. The Thundermans: Adventures in Supersitting (Vol. 1, Ep. 1)(TV)..30

12. Dara Berger--How to Prevent Autism................................................26

13. 1,001 Wines You Must Try Before You Die (ed. Beckett)..................21

14. Taxicab Confessions (TV Series).........................................................6

15. Reynolds Price--Clear Pictures: First Loves, First Guides.................5

16. Marco Polo New York Guide...............................................................3

First Round

#1 Morrison over #16 Marco Polo New York

Not that I don't love travel guides.

#2 James over #15 Price

I don't know what is supposed to be going on with the Price book.

#14 Taxicab Confessions over #3 Taxi

One of the magic words that was used to call up contestants for this tournament was "cab". Taxicab Confessions, while I don't think it is supposed to be particularly good, sounds more interesting than Taxi, which is rated as dreadful despite the appearance of Gisele Bundchen, the wife of Tom Brady of Ted movies fame.

#4 Graham over #13 1,001 Wines

The Poldark books are evidently popular reading, and literarily respectable enough to get the BBC adaptation treatment. I believe my wife has seen the TV series.

#12 Berger over #5 D. C. Cab

This book sounds like a crock, but even that isn't enough to lose to a legendarily bad movie.

#6 Weiner over #11 The Thundermans

#10 Morris over #7 Kalam

Neither of these books is carried by a single library in my state, and neither of them has a title that excites me.

#9 Hawthorne over #8 Langley

Elite Eight

#1 Morrison over #14 Taxicab Confessions

#2 James over #12 Berger

#4 Graham over #10 Morris

#9 Hawthorne over #6 Weiner

This one was a decent contest following three routs.

Final Four

#1 Morrison over #9 Hawthorne

The game of the tournament. I figure it is time I read something by Toni Morrison, and her first book would seem to be a logical starting point for that.

#2 James over #4 Graham

I have mixed feelings about whether I would like the Poldark books or not. Maybe it could win in a different field.

Championship

#1 Morrison over #2 James

"The proud South at first resented and then acclaimed one of its aristocratic daughters for her revolt against the sentimental tradition of her environment. Born in Richmond, Virginia, Ellen Glasgow had all the advantages of education and leisure of the privileged. After taking her degree and winning a Phi Beta Kappa key at the University of Virginia, Miss Glasgow began her career as an author with the publication of an anonymous novel in 1897. In open defiance of the genteel prejudice against women expressing themselves on such controversial subjects as politics, Miss Glasgow staked her reputation and social position on a novel published under her own name. The Voice of the People was an instantaneous success. Since its appearance one novel has followed another and Miss Glasgow's reputation has grown steadily. Today she ranks as one of the leading women novelists of the country..."

I don't know why the IWE refers to her as "Mrs" while the Modern Library uses "Miss".

Taking into consideration her former status, what I perceive to be the general desire for female writers of the past to be more appreciated, and the circumstance that Barren Ground at least is a book of considerable literary quality that even apart from having a quite empowered heroine for its time offers much of value to the national literary landscape, it is perhaps surprising that Ellen Glasgow is not more remembered. I suspect her handling of race, while not overtly mean-spirited or to me obtrusively offensive given her generation and the atmosphere in which she lived, is not adequate to the requirements of our era. Her overall attitude in this area struck me as having some similarity to Faulkner's (which I hear criticized as well), but of course without his subtlety and force to mitigate some of the more obvious objections to be made. This subject will inevitably come up several times during this report.

Remarkably, I cannot recall ever having read a novel set in Virginia before this, which especially stands out to me because I have lived in that state (though it is my least favorite place that I have lived). I suppose I have read some D.C.-set books where one of the characters lived in Arlington or worked at the Pentagon or a Civil War book where some of the camp or battle scenes took place there, but this is the first I can think of with a domestic setting, extensive description of nature and seasons and local society over a period of many years and so forth. I took a lot of notes on it.

p.5 "...the greater number arrived, as they remained, 'good people,' a comprehensive term, which implies, to Virginians, the exact opposite of the phrase, 'a good family.' The good families of the state have preserved, among other things, custom, history, tradition, romantic fiction, and the Episcopal Church. The good people, according to the records of clergymen, which are the only surviving records, have preserved nothing except themselves."

(Early on) This book is part "The Waltons", part As the Earth Turns, with a hint of Faulkner.

Sexuality in old books is (generally speaking) normal. Conventional love affairs, etc, of a brief duration in which the intensity is even more vanishingly fleeting. Instances of women being highly promiscuous, incest, etc, are understood, or at least presumed, to be unusual. Less anxiety for bourgeois readers, which perhaps they need once in a while.

p.43 "Mrs Oakley looked down on the 'poor white' class, though she had married into it...He had made her a good husband; it was not his fault that he could never get on; everything from the start had been against him; and he had always done the best that he could." I hope my wife doesn't read this passage, lest some truths hit too close to home.

p. 81 "Until yesterday Dorinda had regarded the monotonous routine of the store as one of the dreary, though doubtless beneficial, designs of an inscrutable Providence." That "though doubtless beneficial" is a good piece of characterization.

The use of black dialect throughout here is probably such as to be offensive. Glasgow is not a comic writer, so she is going for realism, not humor. I have seen it done worse, but perhaps we don't need quite so much of it to make the point. On the other hand, is there no value in her having made some record of it? Assuming it is accurate. One presumes that she lived among people like these characters, and that their speech was distinct from that common among the whites, and also she was a conscientious writer of well above average literary skill, so "accuracy" insofar as she is presenting her own interpretation of what she heard, does not seem to me to be problematic and would certainly be in accord with literary custom.

Like many older books, this took around 100 pages to get going. My sense is that consensus opinion today holds that that is too long even for supposedly great books and demands way too much of a person's time to be worthwhile in the modern world. I would dispute that of course, because I like what I take to be the expansive effects of leisurely book-reading on my own mind mostly, though I don't think the trend of even smarter younger people moving away from this practice is really benefiting their cognitive development. Such knowledge as they acquire seems to me to be confined with narrower channels into which more reading perhaps would have allowed more air and a more comprehensive vision.

Old books have two main kinds of pregnancy dilemmas. Either the boy is too low status to avoid a forced marriage/have the problem taken care of, or he is too high status to be forced into marriage (from the girl's point of view). We have the second type of that sad story here.

p. 274 "She wished he wouldn't say 'ni**ers.' That scornful label was already archaic, except among the poorest of the 'poor white class' at Pedlar's Mill." This is somewhat progressive, I suppose, but then a few pages later (281-2) there is the somewhat ubiquitous white author denial/avoidance/whitewashing passage that has become mostly inexcusable in our days:

"Like her mother, she was endowed with an intuitive understanding of the negroes; she would always know how to keep on friendly terms with that immature but not ungenerous race. Slavery in Queen Elizabeth County had rested more lightly than elsewhere...It was true that the coloured people about Pedlar's Mill were as industrious and as prosperous as any in the South, and that, within what their white neighbours called reasonable bounds, there was, at the end of the nineteenth century, little prejudice against them...As for the negroes themselves, they lived contentedly enough as inferiors though not dependents."

My copy, alas, did not have this groovy dust jacket.

p. 324 "Mrs. Oakley was a pious and God-fearing woman, whose daily life was lived beneath the ominous shadow of the wrath to come; yet she had deliberately perjured herself in order that a worthless boy might escape the punishment which she knew he deserved." It is my observation that women authors are much more likely, if not to directly refer to certain male characters in such withering terms as "worthless", "inferior", "cowardly", etc, to develop them at greater length and detail before passing down these oracular judgments, which I find gives them a certain sting whose impression lasts longer than the introduction of such characters in male authors, whose purpose more frequently is merely to give the hero someone to defeat or otherwise display his own overwhelming superiority in contrast with, and whose existence or behavior is otherwise of little significance.

p. 326 "The Lord helps good sleepers." I hope so.

p. 365 "She had seen enough of the world to know that you took your husband...where you found him, and she was troubled by few illusions about marriage."

p. 371 "That, she had learned, was the hidden sting of success; it rubbed old sores with the salt of regret until they were raw again."

p. 372 "Yes, that's the trouble about getting comforts. We always remember that other people went without them. I've got the carpets now that Rose Emily wanted." I like this last quote, there seems to me to be something in it. The two previous I am not as convinced of, but in the context of the book I thought what it revealed about its character's point of view was interesting.

p. 443 "It had never seemed possible to her that Nathan could die. He had not mattered enough for that." This is the main character's husband, whom she married at a rather mature age, 38 or so. It is implied in the book that sexual consummation in this marriage was never achieved. The character, Dorinda, had given herself to a lover at age 20 and been jilted, and the plot of the book is essentially the long grind through the rest of her life to renounce passion and love overcome this setback and the exhausted, narrow life of her rural community to become successful and gain a measure of revenge on her onetime lover, who eventually descends into alcoholism and poverty. This aspect of a woman who determines to get along without dependence on or emotional connection to males or to be weighed down by children was actually rather timely given the recent outpouring of female anger and disgust with much of masculine society that has become so prominent in the culture.

p. 511 "I've seen so many people die," she thought, and then, "In fifty years many people must die." I only note this because this is the point of life that I am at now.

p. 521 "Youth can never know the worst, she understood, because the worst that one can know is the end of expectancy."