I am a couple of days late with this month's check-in. The 6th was my 20th anniversary, and yesterday I was very tired. My reading has also slowed a bit due to the nature of some of the works, but you still make some progress even doing a minimal amount every day.

A List: George Eliot--Silas Marner............................................................106/134

B List: Hank James--The Awkward Age.....................................................130/393

C List: Knausgaard, Volume 4...................................................................164/502

It is my first time for all of these. Silas Marner is different from what I was expecting, and I am not entirely sure what I make of it yet. It is well-plotted and is a fairly good read to this point, except for the parts when she has rustics speaking in dialect. I still do not foresee the conclusions of the various threads of the plot. It is a moral work, and one that thus far seems to me to adhere pretty closely to standard 19th century Protestant attitudes, coming down against dishonesty, especially in one's dealings with the community, and profligacy, though the other extreme of profligacy, miserliness, is contrasted with as something of an overreaction, if not quite as utterly wicked.

I write a lot here about my need increasingly to be well-rested and fairly when reading certain authors, most of whom seem to be Victorians of one kind or another, though whether this is due to age, a continuous lack of good sleep, or the effects of the internet and other developments of modern life rotting my brain, I don't know. Henry James of course, especially in his later period (and while in the Awkward Age he has not fully arrived there, it is perhaps the key novel in the transition to it), is the king of writers who require a clear mind and an hour or two with no serious distractions to read with any comprehension. After the first couple of days I had to give up reading him at the end of the day entirely, because it was impossible. I have read a lot of Henry James over the years--eight or nine of the longer novels, a couple of stories, two novelettes (I'm counting Aspern Papers and Turn of the Screw in this category), The Art of Fiction--and I have developed a certain affection for him, though he can be very precious, especially in his much-loved (by very serious and mentally sophisticated people) later books. So far the entire novel of The Awkward Age consists of people sitting in drawing rooms testing each other with conversations and expressions refined to a microscopically fine subtlety. It doesn't look like any other setting or kind of action is going to be introduced any time soon, though the scene does shift every thirty pages or so to a different day and a different drawing room and different combinations of people. I want to like it, and depending on how receptive my mind is on a given day I generally do like it, but the truth, or more to the point, the higher truth and necessity of the later James continues to ultimately elude me I fear.

I started the Knausgaard in the interval between the B-List books while doing the Oliver Wendell Holmes write-up, but I've largely put it down for the past week in order to devote my limited energy to wrestling with the James. Thus far I feel largely the same about him as I have noted here in other postings, I like the books, the writing is personable and intelligent and it really does take me back to my own teen-age years, which, while I admit my prejudice, definitely strike me as a freer and more fun time to be a teenager than now, as well as more conducive to extended concentration and thinking, however unfavorably that period compared to epochs that had come before it. How much time did we used to spend listening to the same ten record albums over and over? This is certainly something people don't do any more.

I was going to put up an old picture commemorating my 20th anniversary, which would not be horribly out of place among these other pictures of beautiful young people, but I didn't get around to it.

Friday, December 8, 2017

Tuesday, November 28, 2017

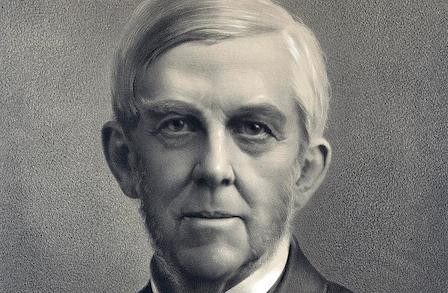

Oliver Wendell Holmes--The Autocrat of the Breakfast Table (1858)

While I liked it, I have to say this is an odd book to take up in 2017. I'm not sure that I will remember anything about it a week from now other than such things as have a direct resonance with me--in this instance the importance of breeding and the need in a young man to have a tireless ambition and drive. Much of the other incidental stuff was not terribly vivid to my mind. Writing in the 1960s, the IWE editor says of the book that it "is generally considered Holmes's masterpiece (which suggests the presence of other contenders. I have actually read his equally florid novel Elsie Venner, if that is one of the contenders the writer has in mind). The introduction goes on to say that "The humor, urbanity, iconoclasm and scholarship of the essays are almost unique for their times and are timeless, being as good reading today as then." As a indicator of how much times have changed, it is almost impossible for me to imagine anyone with credibility saying anything like this today. Once again one is reminded of the question I have often had occasion to ask here, where have all the old Yankee/WASPs gone, even in New England? There were still some around in my youth in the 80s, and in books and articles about the region even from that time the character is still highly prominent compared to now. Have those that are left gone way underground (or over-ground, as the case may be)?

The copy of the book that I bought (online) was a special boxed edition published in 1955 by the Heritage Press of Norwalk, Connecticut, with an introduction by Holmes' fellow super-Brahmin Van Wyck Brooks and nostalgia-inducing pen and ink illustrations by R. J. Holden. It is noted in the introduction that no less a figure than Henry James, Sr (father of the famous philosopher and novelist brothers) called Holmes "the most intellectually alive man I ever knew". Indeed, Holmes's mind was by all accounts the type which the higher sort of formal education once sought to cultivate, yet it is hard to imagine him being broadly admired in this way today, mainly because of his race/gender/caste/ethnicity combination, since his primary sins (social and intellectual snobbery, ethnic chauvinism) are not exactly absent among the classes correspondent to his today, though it seems to be a more intolerable trait when found in a person like Holmes. There is also the problem that however impressive his mind was to his contemporaries, it led him to hold a lot of social views that are not currently held to possess much intelligence, let alone any other value, which naturally throws the quality of the other facets of his mind under suspicion.

It is noted that the takedown of Holmes and the other old Yankee writers began at least as far back as Mencken and the rise of ethnic America, which I guess would include my people, a period now a century in the past.

After the Brooks introduction there are three prefaces written by Holmes himself for each of the three editions that came out in his lifetime, the original in 1858, the later ones in 1882 and 1891, at which latter dates Holmes was 82 years old. These prefaces are consistent in their emphases on technological and scientific progress, which were of course immense over the course of his career (1831-91, roughly, as well as social progress, which he hinted in 1891 of having expectations of great changes in that area in the 20th century, though he did not speculate on the specific forms they might take). He was progressive and elitist at the same time, his progressivism taking the form of believing in the possibility of uplifting the unenlightened peoples of the world to the Anglo-Saxon level, or some facsimile of it. I wrote "we'll see if he lists his views on the potential/proper role for women in the book proper." I don't recall anything worth noting on this matter coming on, but that is why I take notes, because I remember very little of what I read.

p. 1 "We are mere operatives, empirics, and egotists, until we learn to think in letters instead of figures." Of course I want to believe this. Whatever it is, something is missing from the data driven understanding of existence as concerns achieving some sense of wholeness as a human being

.

p. 4 On the virtue of mutual admiration societies of high achieving males: "Foolish people hate and dread and envy such an association of men of varied power and influence, because it is lofty, serene, impregnable, and, by the necessity of the case, exclusive." Do foolish people have a choice in the matter, so far as their essential foolishness can be effected?

I am already noting at this early stage that the book looks to be extremely quotable throughout. Then I wrote that the thinking people (illegible) who have (illegible) lost their taste for this sort of writing seem to think/live after a similar manner.

It's hard to get a cute girl picture to come up in a search for OWH Autocrat, etc, but this Boston duck boat driver will do.

I write my illegible notes in the book in pencil, in which I am hindered by the circumstance that my pencil sharpener does not evenly sharpen the pencils and makes them difficult to write with. I know that there are myriad easy ways to correct this situation, but nothing is really easy with me when it comes to trying to carry out some semblance of the life of the mind. I will never quite permanently solve my pencil problem, or my note taking problem, or my slow writing problem, or any other minor and irritating problem that besets me.

I forgot about when Holmes by way of establishing the mental climate out of which the book arose, introduced it as a world where most people listened to a hundred sermons a year.

Holmes likes a man of family. This hurts for me, since a lot of the more intelligent modern people seem to like that too, and the family that I came out of at least doesn't seem to excite anybody very much. He reverts to this theme several times in the course of the book, lamenting mésalliances in marriage between people whose backgrounds and breeding are not well matched. "No. my friends, I go (always, other things being equal) for the man who inherits family traditions and the cumulative humanities of at least four or five generations."

p. 43 "The woman who calc'lates is lost...Put not your trust in money, but put your money in trust." On matrimony. My poor wife trusted...So much so that she has said that if she were ever to remarry, it would only be for money.

p. 45 "Except in cases of necessity, which are rare, leave your friend to learn unpleasant truths from his enemies; they are ready enough to tell them."

p. 46 "Therefore conversation which is suggestive rather than argumentative, which lets out the most of each talker's results of thought, is commonly the pleasantest and the most profitable." Yes, but we must be convinced that our interlocutor is not an absolute dunce who is even capable of saying anything worth our listening to, which is rare in our time.

p. 54 "How many people live on the reputation of the reputation they might have made!" Not many anymore I wouldn't think. We've set ourselves with some dedication to snuffing out that kind of conceit.

p. 54 "When one of us who has been led by native vanity or senseless flattery to think himself or herself possessed of talent arrives at the full and final conclusion that he or she is really dull, it is one of the most tranquillizing and blessed convictions that can enter a mortal's mind." Yes and no. It may be liberating to an extent for the non-genius himself to realize his limitations, and it is certainly applauded by all the people who were annoyed by his ridiculous pretensions, but the people he has close relationships with who rely on him to some degree do not happily welcome the definitive proof that their fortunes are chained to a dullard with little prospect of improvement.

This is essentially the edition of the book I have, though instead of this teapot I have a red rectangle with a gold border and the initials O.W.H. imprinted on the field in gold letters.

p.58 There was a reference to news from India which was unclear to me, but a little research indicates that he must be referring to the Sepoy Rebellion of 1857. I am so conditioned to assume that insightful and adroit minds even in the past must have at some level been suspicious of the virtues of European colonialism (and certainly some were), that I thought that perhaps Holmes's references to unidentified women and children being outraged and babies being killed were oblique statements against British conduct, and that his referring to the Indians as the inferior race was ironic. But no, he was taking the pro-English position all the way.

Holmes ascribes powers to genuine (high) poetry and its relations/interactions with human souls that may contain some truth, but are largely foreign to the way almost everyone intelligent experiences life now.

He also makes an interesting mechanical comparison of the making of a poem to that of a fine violin, that time is necessary to dry out and fit together the many parts of which it is composed to produce the grand effect.

p. 146 I like the account of his morning rowing around Boston.

Holmes's own poems are interspersed throughout the book. They are for the most part not very good, difficult to read and scant on impressions and images. There are two poems that are moderately famous, or used to be, "The Chambered Nautilus", and "The Wonderful One-Hoss Shay", the latter a comic poem, that are markedly better than the rest.

p. 171 Holmes on people who smile stupidly for no good reason in social interactions: "...it is evident that the consciousness of some imbecility or other is at the bottom of this extraordinary expression. I don't think, however, that these persons are commonly fools. I have known a number, and all of them were intelligent. I think nothing conveys the idea of underbreeding more than this self-betraying smile." Underbreeding seems to me a useful concept that is not discussed nearly enough in our time.

He muses on how "there is no looking glass for the voice", such that people have no real sense of the sound of their own voices, and how pleasant it would be to be able to inhabit another form and be able to observe oneself speaking and moving. (Of course the technology to do this had not yet been developed in the 1850s).

There is a long and pleasant section about the trees of New England which is perhaps of greater interest if one happens to live here. Holmes notes many particular favorites and claims to "have as many tree-wives as Brigham Young has human ones." The loss of our elm trees was such a blow to New England's historical character. Holmes mentions them extensively, as does almost everyone who writes about the region prior to World War II.

Holmes sees the English and American varieties of elms as characteristic of the creative force of the respective countries. The English he describes as "compact, robust, holds its branches up, and carries its leaves for weeks longer than our own native tree", and the American as "tall, graceful, slender-sprayed, and drooping as if from languor." How this is related to the creative force of America especially I am hazy on.

pp. 261-2 "Qu'est-ce qu'il a fait? What has he done? That was Napoleon's test...Is a young man in the habit of writing verses? Then the presumption is that he is an inferior person. For...there are at least nine chances in ten that he writes poor verses." Common knowledge (sort of) now, but worth being reminded of and impressed on the young.

p. 279 "One's breeding shows itself nowhere more than in his religion."

If you have stuck out this post to this point, I thank you and consider you a true friend. I may not exactly be a tortured soul, but I do feel that I never quite made it as a fully accepted member of the educated classes, and I am lonely in my interests.

The Challenge

1. M. R. Carey--The Girl With All the Gifts.......................................................2,525

2. Haraki Murakami--1Q84................................................................................1,687

3. Tana French--The Secret Place.......................................................................1,663

4. Rachel Macy Stafford--Hands Free Mama.......................................................326

5. Jay Winik--1944: FDR & the Year That Changed History...............................301

6. Rachel Macy Stafford--Hands Free Life...........................................................222

7. D. H. Lawrence--Women In Love......................................................................147

8. John Whyte--Is This Normal? The Essential Guide to Middle Age & Beyond...35

9. Kathleen Ann Goonan--In War Times.................................................................28

10. Germany 1945: The Last Months of the War......................................................0

A small, but pretty strong field for our game, with seven 100+ scoring entrants and the top three seeds all north of 1,500!

1st Round

#7 Lawrence over #10 Germany

The Germany book appears to be a bilingual coffee table book of photographs that was published in Germany and has had no U.S. release. I read Women In Love, which does not appear on the IWE list and therefore qualifies for the Challenge, as the second book on my "A" list way back in December of 1994. It was not my favorite book at the time, though a few years later when I was about 28 I read The Rainbow, which preceded it and follows many of the same characters, and liked it very much, though I don't know if I would feel the same about that one if I read it now either.

#9 Goonan over #8 Whyte.

A close battle. The book about aging was not tempting enough to me to give it the edge here.

Final Eight

#9 Goonan over #1 Carey

Carey is a dreaded genre book. Also my library didn't have it.

#7 Lawrence over #2 Murakami

I was a little excited about the Murakami, which seems to have the status of a contemporary instant classic, but at 925 pages and with a tough matchup in its first game, it falls.

#6 Stafford over #3 French

French is a mega-genre writer, and her book is long. Plus Rachel Macy Stafford is a Generation X (b. 1972) supermom/superwife, Southern Christian variety, and what is not to like about that (if you're me)?

#4 Stafford over #5 Winik

While I acknowledge I have a crush on Rachel Macy Stafford, that is not the whole reason why she triumphs here over a major history. The 1,027 page length of the competitor's offering was what mainly killed it. Jay Winik has a demonstrated fondness for identifying years or even months that changed everything and writing books about them. Another title of his is April 1865: The Month That Saved America.

Final Four

#9 Goonan over #4 Stafford

#7 Lawrence over #6 Stafford

I was feeling guilty about passing over so much literature.

Championship

#9 Goonan over #7 Lawrence

Upset special. The Goonan is another science fiction book, which I have not have good experiences with so far (ed--apart from the Ray Bradbury book; I liked a lot of those stories), but I am willing to give it another try.

The copy of the book that I bought (online) was a special boxed edition published in 1955 by the Heritage Press of Norwalk, Connecticut, with an introduction by Holmes' fellow super-Brahmin Van Wyck Brooks and nostalgia-inducing pen and ink illustrations by R. J. Holden. It is noted in the introduction that no less a figure than Henry James, Sr (father of the famous philosopher and novelist brothers) called Holmes "the most intellectually alive man I ever knew". Indeed, Holmes's mind was by all accounts the type which the higher sort of formal education once sought to cultivate, yet it is hard to imagine him being broadly admired in this way today, mainly because of his race/gender/caste/ethnicity combination, since his primary sins (social and intellectual snobbery, ethnic chauvinism) are not exactly absent among the classes correspondent to his today, though it seems to be a more intolerable trait when found in a person like Holmes. There is also the problem that however impressive his mind was to his contemporaries, it led him to hold a lot of social views that are not currently held to possess much intelligence, let alone any other value, which naturally throws the quality of the other facets of his mind under suspicion.

It is noted that the takedown of Holmes and the other old Yankee writers began at least as far back as Mencken and the rise of ethnic America, which I guess would include my people, a period now a century in the past.

After the Brooks introduction there are three prefaces written by Holmes himself for each of the three editions that came out in his lifetime, the original in 1858, the later ones in 1882 and 1891, at which latter dates Holmes was 82 years old. These prefaces are consistent in their emphases on technological and scientific progress, which were of course immense over the course of his career (1831-91, roughly, as well as social progress, which he hinted in 1891 of having expectations of great changes in that area in the 20th century, though he did not speculate on the specific forms they might take). He was progressive and elitist at the same time, his progressivism taking the form of believing in the possibility of uplifting the unenlightened peoples of the world to the Anglo-Saxon level, or some facsimile of it. I wrote "we'll see if he lists his views on the potential/proper role for women in the book proper." I don't recall anything worth noting on this matter coming on, but that is why I take notes, because I remember very little of what I read.

p. 1 "We are mere operatives, empirics, and egotists, until we learn to think in letters instead of figures." Of course I want to believe this. Whatever it is, something is missing from the data driven understanding of existence as concerns achieving some sense of wholeness as a human being

.

p. 4 On the virtue of mutual admiration societies of high achieving males: "Foolish people hate and dread and envy such an association of men of varied power and influence, because it is lofty, serene, impregnable, and, by the necessity of the case, exclusive." Do foolish people have a choice in the matter, so far as their essential foolishness can be effected?

I am already noting at this early stage that the book looks to be extremely quotable throughout. Then I wrote that the thinking people (illegible) who have (illegible) lost their taste for this sort of writing seem to think/live after a similar manner.

It's hard to get a cute girl picture to come up in a search for OWH Autocrat, etc, but this Boston duck boat driver will do.

I write my illegible notes in the book in pencil, in which I am hindered by the circumstance that my pencil sharpener does not evenly sharpen the pencils and makes them difficult to write with. I know that there are myriad easy ways to correct this situation, but nothing is really easy with me when it comes to trying to carry out some semblance of the life of the mind. I will never quite permanently solve my pencil problem, or my note taking problem, or my slow writing problem, or any other minor and irritating problem that besets me.

I forgot about when Holmes by way of establishing the mental climate out of which the book arose, introduced it as a world where most people listened to a hundred sermons a year.

Holmes likes a man of family. This hurts for me, since a lot of the more intelligent modern people seem to like that too, and the family that I came out of at least doesn't seem to excite anybody very much. He reverts to this theme several times in the course of the book, lamenting mésalliances in marriage between people whose backgrounds and breeding are not well matched. "No. my friends, I go (always, other things being equal) for the man who inherits family traditions and the cumulative humanities of at least four or five generations."

p. 43 "The woman who calc'lates is lost...Put not your trust in money, but put your money in trust." On matrimony. My poor wife trusted...So much so that she has said that if she were ever to remarry, it would only be for money.

p. 45 "Except in cases of necessity, which are rare, leave your friend to learn unpleasant truths from his enemies; they are ready enough to tell them."

p. 46 "Therefore conversation which is suggestive rather than argumentative, which lets out the most of each talker's results of thought, is commonly the pleasantest and the most profitable." Yes, but we must be convinced that our interlocutor is not an absolute dunce who is even capable of saying anything worth our listening to, which is rare in our time.

p. 54 "How many people live on the reputation of the reputation they might have made!" Not many anymore I wouldn't think. We've set ourselves with some dedication to snuffing out that kind of conceit.

p. 54 "When one of us who has been led by native vanity or senseless flattery to think himself or herself possessed of talent arrives at the full and final conclusion that he or she is really dull, it is one of the most tranquillizing and blessed convictions that can enter a mortal's mind." Yes and no. It may be liberating to an extent for the non-genius himself to realize his limitations, and it is certainly applauded by all the people who were annoyed by his ridiculous pretensions, but the people he has close relationships with who rely on him to some degree do not happily welcome the definitive proof that their fortunes are chained to a dullard with little prospect of improvement.

This is essentially the edition of the book I have, though instead of this teapot I have a red rectangle with a gold border and the initials O.W.H. imprinted on the field in gold letters.

p.58 There was a reference to news from India which was unclear to me, but a little research indicates that he must be referring to the Sepoy Rebellion of 1857. I am so conditioned to assume that insightful and adroit minds even in the past must have at some level been suspicious of the virtues of European colonialism (and certainly some were), that I thought that perhaps Holmes's references to unidentified women and children being outraged and babies being killed were oblique statements against British conduct, and that his referring to the Indians as the inferior race was ironic. But no, he was taking the pro-English position all the way.

Holmes ascribes powers to genuine (high) poetry and its relations/interactions with human souls that may contain some truth, but are largely foreign to the way almost everyone intelligent experiences life now.

He also makes an interesting mechanical comparison of the making of a poem to that of a fine violin, that time is necessary to dry out and fit together the many parts of which it is composed to produce the grand effect.

p. 146 I like the account of his morning rowing around Boston.

Holmes's own poems are interspersed throughout the book. They are for the most part not very good, difficult to read and scant on impressions and images. There are two poems that are moderately famous, or used to be, "The Chambered Nautilus", and "The Wonderful One-Hoss Shay", the latter a comic poem, that are markedly better than the rest.

p. 171 Holmes on people who smile stupidly for no good reason in social interactions: "...it is evident that the consciousness of some imbecility or other is at the bottom of this extraordinary expression. I don't think, however, that these persons are commonly fools. I have known a number, and all of them were intelligent. I think nothing conveys the idea of underbreeding more than this self-betraying smile." Underbreeding seems to me a useful concept that is not discussed nearly enough in our time.

He muses on how "there is no looking glass for the voice", such that people have no real sense of the sound of their own voices, and how pleasant it would be to be able to inhabit another form and be able to observe oneself speaking and moving. (Of course the technology to do this had not yet been developed in the 1850s).

There is a long and pleasant section about the trees of New England which is perhaps of greater interest if one happens to live here. Holmes notes many particular favorites and claims to "have as many tree-wives as Brigham Young has human ones." The loss of our elm trees was such a blow to New England's historical character. Holmes mentions them extensively, as does almost everyone who writes about the region prior to World War II.

Holmes sees the English and American varieties of elms as characteristic of the creative force of the respective countries. The English he describes as "compact, robust, holds its branches up, and carries its leaves for weeks longer than our own native tree", and the American as "tall, graceful, slender-sprayed, and drooping as if from languor." How this is related to the creative force of America especially I am hazy on.

pp. 261-2 "Qu'est-ce qu'il a fait? What has he done? That was Napoleon's test...Is a young man in the habit of writing verses? Then the presumption is that he is an inferior person. For...there are at least nine chances in ten that he writes poor verses." Common knowledge (sort of) now, but worth being reminded of and impressed on the young.

p. 279 "One's breeding shows itself nowhere more than in his religion."

If you have stuck out this post to this point, I thank you and consider you a true friend. I may not exactly be a tortured soul, but I do feel that I never quite made it as a fully accepted member of the educated classes, and I am lonely in my interests.

The Challenge

1. M. R. Carey--The Girl With All the Gifts.......................................................2,525

2. Haraki Murakami--1Q84................................................................................1,687

3. Tana French--The Secret Place.......................................................................1,663

4. Rachel Macy Stafford--Hands Free Mama.......................................................326

5. Jay Winik--1944: FDR & the Year That Changed History...............................301

6. Rachel Macy Stafford--Hands Free Life...........................................................222

7. D. H. Lawrence--Women In Love......................................................................147

8. John Whyte--Is This Normal? The Essential Guide to Middle Age & Beyond...35

9. Kathleen Ann Goonan--In War Times.................................................................28

10. Germany 1945: The Last Months of the War......................................................0

A small, but pretty strong field for our game, with seven 100+ scoring entrants and the top three seeds all north of 1,500!

1st Round

#7 Lawrence over #10 Germany

The Germany book appears to be a bilingual coffee table book of photographs that was published in Germany and has had no U.S. release. I read Women In Love, which does not appear on the IWE list and therefore qualifies for the Challenge, as the second book on my "A" list way back in December of 1994. It was not my favorite book at the time, though a few years later when I was about 28 I read The Rainbow, which preceded it and follows many of the same characters, and liked it very much, though I don't know if I would feel the same about that one if I read it now either.

#9 Goonan over #8 Whyte.

A close battle. The book about aging was not tempting enough to me to give it the edge here.

Final Eight

#9 Goonan over #1 Carey

Carey is a dreaded genre book. Also my library didn't have it.

#7 Lawrence over #2 Murakami

I was a little excited about the Murakami, which seems to have the status of a contemporary instant classic, but at 925 pages and with a tough matchup in its first game, it falls.

#6 Stafford over #3 French

French is a mega-genre writer, and her book is long. Plus Rachel Macy Stafford is a Generation X (b. 1972) supermom/superwife, Southern Christian variety, and what is not to like about that (if you're me)?

#4 Stafford over #5 Winik

While I acknowledge I have a crush on Rachel Macy Stafford, that is not the whole reason why she triumphs here over a major history. The 1,027 page length of the competitor's offering was what mainly killed it. Jay Winik has a demonstrated fondness for identifying years or even months that changed everything and writing books about them. Another title of his is April 1865: The Month That Saved America.

Final Four

#9 Goonan over #4 Stafford

#7 Lawrence over #6 Stafford

I was feeling guilty about passing over so much literature.

Championship

#9 Goonan over #7 Lawrence

Upset special. The Goonan is another science fiction book, which I have not have good experiences with so far (ed--apart from the Ray Bradbury book; I liked a lot of those stories), but I am willing to give it another try.

Monday, November 6, 2017

November Check In

"A" List: Jules Verne--Journey to the Center of the Earth.....................................28/195

"B" List: Oliver Wendell Holmes (Sr)--The Autocrat of the Breakfast Table........80/281

"C" List: Sol Stein--Stein on Writing....................................................................253/308

Three white guys, though one at least wrote in a foreign language, and Stein is still alive, albeit at age 91 he would appear to be superannuated as far as the current literary scene is concerned.

Jules Verne's books (I wrote about Around the World in Eighty Days in these pages earlier this year) have a decidedly fun quality about them, in addition to being intelligent/depicting intelligent people. I had not especially looked forward to reading any of his books though I had known some were coming for a long time, but I will from now on.

I like the Holmes too, perhaps because there is truly nothing like him being published today (not that there needs to be) and I suspect there is a lot in him that tells about the kind of country and region that we used to have here. He is however another high Victorian writer with an elaborate, somewhat overblown style whom I need to be well rested to concentrate on.

I remarked in an earlier post that I didn't think I was going to like the Stein book, but that turned out not to be the case. I actually found it encouraging, when I was expecting the opposite. Most of the advice I have kind of absorbed intuitively over the years, which is encouraging in itself. I think I have gotten out of it what I needed to get out of it. While it does not exactly repeat itself after the first eighty pages or so, I feel like I've got the idea, which is, briefly, that there are things any intelligent person with a little instinct for language can do will help your writing, and by extension your overall thinking. The book was published in 1995, so even though the blurb notes that Stein works at a couple of How-to-Write type webpages the internet and its particular flavor of writing as we know it had not exploded yet. One indication to me of the pre-internet mindset that I to some extent cane of age in is that Stein is strongly biased towards the form of fiction as more conducive to effective writing than that of non-fiction, which is not a sentiment I see much of anywhere in the present.

"B" List: Oliver Wendell Holmes (Sr)--The Autocrat of the Breakfast Table........80/281

"C" List: Sol Stein--Stein on Writing....................................................................253/308

Three white guys, though one at least wrote in a foreign language, and Stein is still alive, albeit at age 91 he would appear to be superannuated as far as the current literary scene is concerned.

Jules Verne's books (I wrote about Around the World in Eighty Days in these pages earlier this year) have a decidedly fun quality about them, in addition to being intelligent/depicting intelligent people. I had not especially looked forward to reading any of his books though I had known some were coming for a long time, but I will from now on.

I like the Holmes too, perhaps because there is truly nothing like him being published today (not that there needs to be) and I suspect there is a lot in him that tells about the kind of country and region that we used to have here. He is however another high Victorian writer with an elaborate, somewhat overblown style whom I need to be well rested to concentrate on.

I remarked in an earlier post that I didn't think I was going to like the Stein book, but that turned out not to be the case. I actually found it encouraging, when I was expecting the opposite. Most of the advice I have kind of absorbed intuitively over the years, which is encouraging in itself. I think I have gotten out of it what I needed to get out of it. While it does not exactly repeat itself after the first eighty pages or so, I feel like I've got the idea, which is, briefly, that there are things any intelligent person with a little instinct for language can do will help your writing, and by extension your overall thinking. The book was published in 1995, so even though the blurb notes that Stein works at a couple of How-to-Write type webpages the internet and its particular flavor of writing as we know it had not exploded yet. One indication to me of the pre-internet mindset that I to some extent cane of age in is that Stein is strongly biased towards the form of fiction as more conducive to effective writing than that of non-fiction, which is not a sentiment I see much of anywhere in the present.

Friday, October 27, 2017

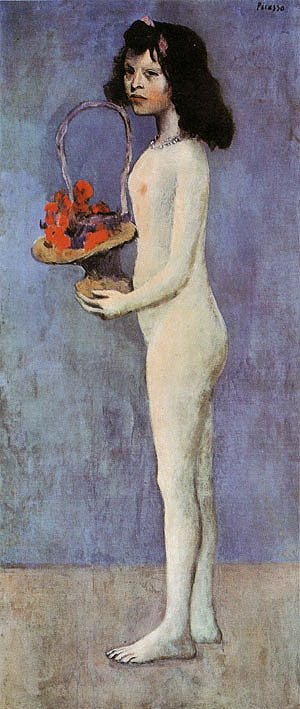

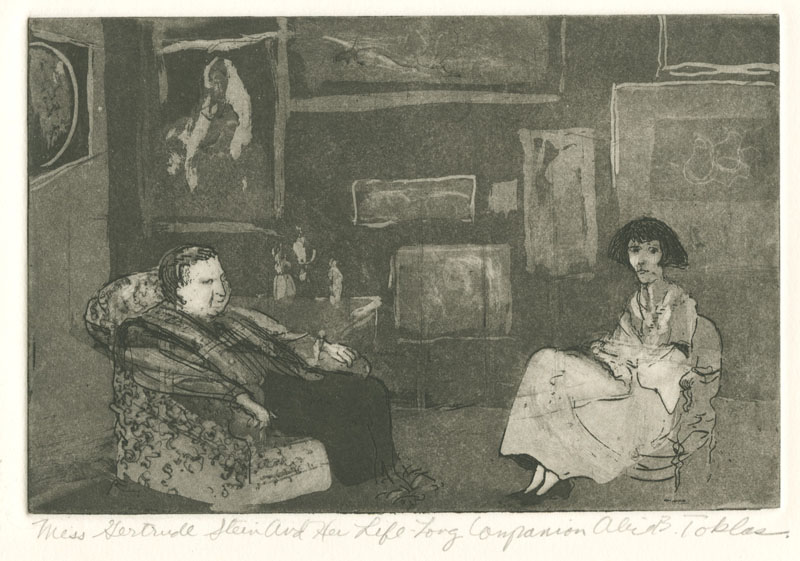

Gertrude Stein--The Autobiography of Alice B Toklas (1933)

Perhaps the most celebrated Americans in Paris book of them all, by the middle I was staying up late consuming baguettes and wine by the light of the stub of a candle babbling to my imaginary brilliant friends with even more fervency than usual. I enjoyed it very much, and was very into it. It is written as if it were a more or less true account of the lives of Gertrude Stein and Alice B Toklas. Evidently considerable portions of the book are not "true" or have been greatly embellished or whitewashed, though whether this is done to the point of being problematic I am not convinced. The point of literary and artistic production, which some people in our time seem to have forgotten, is to capture and fuse the all too fleeting highlights into an elevated sense of life, which is certainly accomplished here. Once I happened by accident to acquire an earlier draft of Boswell's Journey to the Hebrides that had been printed for the use of scholars and other curious parties. While it probably gave a more accurate sense of what the journey was really like on a day in, day out basis, it naturally lacked the high spirit and beauty of the published book that is what is of main interest to readers. Naturally a similar magic of time and place and character pervades this book as well.

I made a lot of notes on this book. Between the epigrammatic style and the characteristic anecdotes of many of the Notable and Great there is much material of the highest interest to me. So this will be a long posting.

As I moved through this I had occasion to do some internet searches about Gertrude Stein and other personages from the book, and I noted that a lot of the biographical sources pointedly identify her as a "Jewish-American writer". Once I saw that it struck me that of course she was, but I had had no conscience sense of it in reading the book because she never makes any reference to herself, or her parents or siblings or other relatives, as being Jewish or doing anything that might be considered explicitly characteristic of a Jewish identity. The only appearance of the word "Jew" in the book comes when Gertrude Stein remarks that a visitor to the house whose appearance she did not like "looks like a Jew", to which her interlocutor (Alfy Maurer, described as "an old habitué of the house") replies "he is worse than that," after which the matter is dropped.

The famous line(s) about Gertrude Stein conversing with the geniuses while Alice talked to the wives. There don't seem to have been any other women geniuses apart of course from Gertrude Stein.

p. 27 "Van Dongen (a painter) in these days was poor, he had a dutch wife who was a vegetarian and they lived on spinach. Van Dongen frequently escaped from the spinach to a joint in Montmartre

where the girls paid for his dinner and his drinks." I have to admit, I love the idea of this kind of life, absent the poverty. But if one has to be poor, Montmartre circa 1905 seems like the way to go.

p. 27 again, on a woman visitor to the house in these early years (Evelyn Thaw, "the heroine of the moment": "She was so blonde, so pale, so nothing, and Fernande (Picasso's live in companion at the time) would give a heavy sigh of admiration." I love that "so nothing" (!)

I had never heard the story about the infuriated public trying to scratch off the paint at one of Matisse's early exhibitions. That's insane.

p. 35 "In those days (we are still in the 1903-1907 chapter. I will note when we move on in time.) you were always going up stairs and down stairs."

I suppose I should say something about the techniques of a) writing another person's autobiography and/or b) writing your own autobiography in the guise of another person. It is done really well here and works beguilingly. As a class of reader who favors execution over novelty, I would love to read other books after the same pattern if they were done as well.

p. 49 My note--We can skip Picasso on Americans. We won't learn anything.

p. 50 Or maybe not. "There was a type of american art student, male, that used very much to afflict him, he used to say no it is not her who will make the future glory of America."

p. 52 "Baltimore is famous for the delicate sensibilities and conscientiousness of its inhabitants." I had never heard nor noticed this. One's instinct is to take it as dated information, but I am slowly coming around to the belief that if you dig deep enough there is no dated information.

p. 60 Still in the 1903-1907 chapter, but a good observation looking somewhat ahead, to the future death of the poet and bon vivant Guillaume Apollinaire: "It was the moment just after the war when many things had changed and people naturally fell apart." The breakup over time of this great prewar Montmartre-based circle of young artistic people with Picasso at the center is one of the more poignant partts of the book, though the twin (narrative) excitements of World War I followed by the emergence of a second group of youthful artists in the 20s mitigates some of the effect of contemplating the fleetingness of almost all really meaningful social intercourse.

p. 77 "Because Picasso is a spaniard and life is tragic and bitter and unhappy."

Now I am in the section "Gertrude Stein Before She Came to Paris". In the part where she talks about having been William James's favorite student in her college years I noted "real genius finds its like." Now I suspect this relationship may perhaps be one of the parts of the book that may been embellished, slightly or otherwise. A little embellishment of this sort does not really bother me if it improves the book.

That chapter was short, and I'm in the 1907-1914 chapter, which is probably the central one in the book.

p. 88 "Gertrude Stein insisted that no one could go to Assisi except on foot." I could still get to Assisi someday I suppose, though it isn't easy to see when that might happen, or what other options might pull me in a different direction if I ever do go anywhere again.

p. 91 "I always remember Picasso saying disgustedly apropos some germans who said they liked bull-fights, they would, he said angrily, they like bloodshed. To a spaniard it is not bloodshed, it is ritual." Ritual is deep and meaningful. People who don't have it are lacking in understanding.

p. 107 A very beautiful passage about the aftermath of a Montmartre party: "It was all very peaceful and about three o'clock in the morning we all went into the atelier where Salmon had been deposited and where we had left our hats and coats to get them to go home. There on the couch lay Salmon peacefully sleeping and surrounding him, half chewed, were a box of matches, a petit bleu and my yellow fantaisie. Imagine my feelings even at three o'clock in the morning. However, Salmon woke up very charming and very polite and we all went out into the street together. All of a sudden with a wild yell Salmon rushed down the hill." For some reason it was this particular memory that inspired me to write "I am dead inside" beside it in the margin.

Great photo of the celebrated duo at home.

p. 111 "I could perfectly understand Fernande's liking for Eve. As I said Fernande's great heroine was Evelyn Thaw, small and negative." I laughed.

p. 112 "And so Picasso left Montmartre never to return." Extremely poignant. The great spirit's time among this scene at least has passed.

p. 125 After the Italian futurists' big Paris show. "Jacques-Emile Blanche was terribly upset by it. We found him wandering tremblingly in the garden of the Tuileries and he said, it looks alright but is it. No it isn't, said Gertrude Stein. You do me good, said Jacques-Emile Blanche."

Now I've advanced to the chapter titled "The War." Whenever the opening scenes in the summer of 1914 appear in a novel written by someone with firsthand reminiscence of the time, whether in Russia, or France, or Austria, or anywhere else, it is always good, and always serves as a jolt to the book. The emotional upheaval of that initial embarking into war was obviously incredible, and one of the defining periods in the lives of everyone who lived through it.

p. 172 More name-dropping, as Picasso is hanging with the young Jean Cocteau! with whom he was heading to Italy. "One day Picasso came in and with him and leaning on his shoulder was a slim elegant youth." Oh yes. "Everybody was at the war, life in Montparnasse was not very gay...he too (Picasso) needed a change." Picasso and Cocteau would spend a lot of time together over the next 50 years, even appearing on celluloid together in Cocteau's 1960 film Orpheus Descending, which I was immediately recalled to when I came on this paragraph.

p. 187 (Driving through the north of France at the end of the war in the service of the American Fund For French Wounded) "Soon we came to the battle-fields and the lines of trenches for both sides. To anyone who did not see it as it was then it is impossible to imagine it. It was not terrifying it was strange." For what it's worth. Stein and Toklas, who lived until 1946 and 1967 respectively, also waited out World War II in France, though they moved out of Paris to the Auvergne-Rhone-Alpes region for the duration. Their friend Bernard Fay, who appears in the latter part of this book, became a high ranking official in the Vichy regime and seems to have arranged for the safety both of their persons and of Stein's art collection. In both written works and interviews that it doesn't seem to have been necessary to have made (she could have returned to America, at least before the occupation set in, for example) Stein made some incredibly naïve, tone-deaf, obtuse statements in praise of the collaborationist government. Considering all of this, her reputation doesn't seem to have taken that much of a hit, in that I think it's still considered O.K. to read about her and her scene in the happier times. Perhaps because she was a woman, and Jewish as well, her conduct during this period has been to some extent excused (on account of) her (being) comparatively powerless and not really understanding what was going on? Though given the resources she had access to, her American citizenship, and her fame in international high culture circles, I can't consider her to be that powerless. Maybe people feel that it doesn't matter, or that she really was a unique sort of genius and cannot be expected to experience moral crises and the like the same way that other people do. Picasso stayed in Paris during the occupation, which I had not realized, though he seems to have lain low and not exhibited any paintings during those years. Anecdotes on Wikipedia indicate that there was antagonism between him and the Germans. Of course everyone is in a different position relative to danger/power, etc in such times of turmoil, yet if we would be good we are expected to hold and behave with more or less the same attitude.

p. 189 "We once more returned to a changed Paris." After the war. I always in books and other art like the theme of how times change, the charm (? I can't read my note) if you are in it, and it is stimulating (and you are thinking?)

Now we are in the postwar (1919-1932) period. Hemingway has shown up. While Hemingway may have been an unbearable jerk later in life when he became famous and was surrounded by sycophants if he was hanging out with anybody at all, he seems to been a very attractive person as a young man, with a charming, life of the party type of energy. I found in this part that I missed him when he wasn't there, and he seems to have been generally popular with the older as well as the younger writers. I even thought he made a pretty good joke (p.200): "(Hemingway) said, when you matriculate at the University of Chicago you write down just what accent you will have and they give it to you when you graduate."

p. 212 Stein on the Hemingway era: "It became the period of being twenty-six. During the next two or three years all the young men were twenty-six years old. It was the right age apparently for that time and place."

p. 213 "Hemingway had then and has always (had) a very good instinct for finding apartments in strange but pleasing localities and good femmes de ménage and good food."

p. 238 "Gertrude Stein did not like hearing him (Paul Robeson, who was brought to the house) sing spirituals. They do not belong to you any more than anything else, so why claim them, she said. he did not answer...Gertrude Stein concluded that negroes were not suffering from persecution, they were suffering from nothingness. She always contends that the african is not primitive, he has a very ancient but a very narrow culture and there it remains. Consequently nothing does or can happen." I assume these statements were based on some thought process which is not however explored or elaborated on further. So I can't really understand what is meant by them.

p. 246 "(our finnish servant) finds it difficult to understand why we are not more modern (with regard to modern conveniences, electricity, radiators, etc). Gertrude Stein says that if you are way ahead with your head you naturally are old fashioned and regular in your daily life." Of course I am comparatively old fashioned and regular in my daily life, so this appealed to me.

p. 251 "Bowles told Gertrude Stein and it pleased her that Copland said threateningly to him when as usual in the winter he was neither delightful nor sensible, if you do not work now when you are twenty when you are thirty. nobody will love you." I have lived that. It is true. I try very hard to impress the fact upon my children.

I did love this book but seeing as it has taken me almost three weeks to do this report I also am missing the old warhorse books that make up this list and I am looking forward to getting back to it.

The Challenge

1. Edith Hamilton--Mythology................................................................647

2. Vampyr (movie-1932).........................................................................127

3. Harry Dolan--Very Bad Men...............................................................117

4. The Disappearance of Eleanor Rigby: Him (movie)............................91

5. Laurie R. King--Mary Russell's War....................................................84

6. Gay Talese--The Voyeurs' Motel..........................................................75

7. Stephanie Powell Watts--No One is Coming to Save Us.....................62

8. Robert Sussman--The Myth of Race.....................................................60

9. Luke Timothy Johnson--The New Testamant: A Very Short Introduc.17

10. T. A. Belshaw--Out of Control...........................................................12

11. Glass Animals--Zaba (record)..............................................................5

12. The Good Immigrant (ed. Nikesh Shukla)...........................................5

13. Merry A. Foresta--Artists Unframed....................................................3

14. Al Jolson--"California Here I Come" (record).....................................2

15. The World of Matisse 1869-1954.........................................................2

16. History of Gambling in America..........................................................1

1st Round

#1 Hamilton over #16 History of Gambling

Hamilton is a past champion of the challenge, and I enjoyed her book very much and found it useful. There is no rule banning past champions from competing again if they qualify (only books from the IWE list itself are ineligible), though in general I will probably prevent them from winning unless there is no desirable competition.

#15 Matisse over #2 Vampyr

#3 Dolan over #14 Jolson

#4 Rigby over #13 Foresta

One of those dreaded allotted upsets.

#5 King over #12 Good Immigrant

The Good Immigrant appears to be a British anthology. There aren't any copies of it in any of my libraries.

#11 Glass Animals over #6 Talese

I was actually excited to see Talese qualify for the Challenge. Unfortunately the Glass Animals had a designated upset to burn, and they burned it here.

#7 Watts over #10 Belshaw

#8 Sussman over #9 Johnson

2nd Round

#1 Hamilton over #15 Matisse

I was inclined to choose the Matisse here, but Hamilton comes in with all kinds of backup advantages to push through the early rounds.

#3 Dolan over #11 Glass Animals

#8 Sussman over #4 Rigby

#5 King over #7 Watts

This was a real battle, as these books are similar both in length and date of publication. King has a slight edge in all of the distinguishing categories however--1 year older, 22 more reviews, 71 pages shorter, etc.

Final Four

#1 Hamilton over #8 Sussman

If Hamilton had not already won the championship she would have easily carried off the title here. The Sussman looked interesting, though for some reason I thought it dated from the 50s, which would have made it more interesting. It actually was published in 2014, which causes me to be a little distrustful of it, as it would to be making an argument for a position that all respectable people, and most scientists as well, already seem to accept as fact.

#3 Dolan over #5 King

Dolan seems to be another murder book. I want to minimize those as much as possible since they quickly become repetitive, to me. The King, however, is a similar kind of book, and Dolan comes in with an upset card that he hasn't needed in the first two rounds against musical acts.

Championship

#3 Dolan over #1 Hamilton

I decided to see how the tournament played out and to have Hamilton drop the final unless the opponent was impossible. Dolan is not quite impossible and he is the survivor from the other side of the draw, so he gets an improbable victory.

The Winner. Born: Rome, N.Y. Colgate University. Age uncertain.

Friday, October 6, 2017

October Report

A List: Carroll, Alice in Wonderland.................................................................101/120

B List: Gertrude Stein, Autobiography of Alice B.Toklas..................................214/252

C List: Charlaine Harris, A Bone to Pick...........................................................131/262

Two books with "Alice" in the title is an interesting coincidence.

I know it hasn't been that long since I read about Alice for the IWE list and wrote about it here. However it had never come up on the A list before and sometimes it happens that certain books will have their turn come up on both lists fairly close in time--this occurred with The Age of Reason. The repetition does not bother me, in fact I find it helpful, since I don't actually have a very thorough familiarity with most of the central books in this line I have been following.

The Charlaine Harris book is one of a series of light, perhaps even mildly goofy, mysteries in which the sleuth is a librarian in a small town in Texas. There is some humor in it however, and a good pace, and I am enjoying it as a change from what I usually read. It was published in 1992, so it takes place in that pre-internet world of my young adulthood that I miss sometimes, though mostly I think because I don't travel or go to parties or fun social events anymore and I associate all of these fun things with that particular period of my life the end of which happened to coincide with the rise of ubiquitous technology and the increasingly sour national preoccupation with politics. But still, characters within the period of my own experience reading newspapers and looking up information in books, how can I resist?

Due to an extra block of words that did not properly belong to any particular book on the IWE list that I did not know what to do with, I decided to have a Bonus Mini-Challenge. Needless to say, one of the words used to generate results was "Stein".

1. Sol Stein--Stein on Writing....................................................................288

2. Sol Stein--How to Grow a Novel..............................................................61

3. Sol Stein--Reference Book for Writers.................................................... 10

For the record, I had #2 beat #3 and #1 beat #2 and I have already secured my copy of #1. It looks like it's going to make me feel bad about myself, since it is about serious professional level writing as practiced in the latter part of the 20th century, which must remind me in some way of everything that bothers me about my life. Well, tough, right. Take your medicine, boy.

B List: Gertrude Stein, Autobiography of Alice B.Toklas..................................214/252

C List: Charlaine Harris, A Bone to Pick...........................................................131/262

Two books with "Alice" in the title is an interesting coincidence.

I know it hasn't been that long since I read about Alice for the IWE list and wrote about it here. However it had never come up on the A list before and sometimes it happens that certain books will have their turn come up on both lists fairly close in time--this occurred with The Age of Reason. The repetition does not bother me, in fact I find it helpful, since I don't actually have a very thorough familiarity with most of the central books in this line I have been following.

The Charlaine Harris book is one of a series of light, perhaps even mildly goofy, mysteries in which the sleuth is a librarian in a small town in Texas. There is some humor in it however, and a good pace, and I am enjoying it as a change from what I usually read. It was published in 1992, so it takes place in that pre-internet world of my young adulthood that I miss sometimes, though mostly I think because I don't travel or go to parties or fun social events anymore and I associate all of these fun things with that particular period of my life the end of which happened to coincide with the rise of ubiquitous technology and the increasingly sour national preoccupation with politics. But still, characters within the period of my own experience reading newspapers and looking up information in books, how can I resist?

Due to an extra block of words that did not properly belong to any particular book on the IWE list that I did not know what to do with, I decided to have a Bonus Mini-Challenge. Needless to say, one of the words used to generate results was "Stein".

1. Sol Stein--Stein on Writing....................................................................288

2. Sol Stein--How to Grow a Novel..............................................................61

3. Sol Stein--Reference Book for Writers.................................................... 10

For the record, I had #2 beat #3 and #1 beat #2 and I have already secured my copy of #1. It looks like it's going to make me feel bad about myself, since it is about serious professional level writing as practiced in the latter part of the 20th century, which must remind me in some way of everything that bothers me about my life. Well, tough, right. Take your medicine, boy.

Thursday, September 28, 2017

Ireland

1. Dublin..............................................17

2. Galway.............................................11

3. Mayo.................................................5

4. Cork...................................................2

5. Kerry..................................................1

Longford............................................1

Roscommon.......................................1

Sligo...................................................1

Tipperary……………………………1

2. Galway.............................................11

3. Mayo.................................................5

4. Cork...................................................2

5. Kerry..................................................1

Longford............................................1

Roscommon.......................................1

Sligo...................................................1

Tipperary……………………………1

Thursday, September 21, 2017

Elizabeth Barrett Browning--Aurora Leigh (1856)

A week ago, as I began to try to organize this report, I was overcome, as I frequently am, for several days with one of the stronger instances I have yet had of the futility of all of these pursuits (i.e. reading, though this could be expanded to any area of study or investigation usually thought of as requiring intellect), seeing as, as I have frequently noted, they have long ceased to lead to any noticeable improvement in either my thinking or personality. This aside however, I think the real problem is that I am no longer in regular contact with anyone who lives any kind of intellectual-artistic life even semi-professionally, which turns all of it into something remote and unreal, a sort of play-acting. I was brought somewhat out of this mood by watching several of the extra features on the Criterion Collection DVD of Robert Bresson's 1983 movie, L'Argent, which happened to be his last film. As a side note I had somehow never heard of Bresson until I was out of college, even though I later found out that he was well-loved there and one of the professors gave a lecture or published something serious on the subject of his films. Anyway the special features included a half-hour Q & A session featuring the aged director at the 1983 Cannes Film Festival, as well as a very well done video essay of about 45 minutes titled "Bresson A to Z" which explores some of the recurrent themes in his work, such as "doors", "hands", "ellipsis", etc, in an illuminating manner. The Q & A (with a nearly entirely French audience; the moderator translated all of the questions into English but none of the participants appears to be an English speaker) is notable mainly because Bresson is largely dismissive of the pedestrian questions that are posed to him, either by returning with a question of his own as to what the other person means as if he had said nothing at all, or if a supposition is included in the question ("There is no hope at the end of the film...") he will counter that of course the exact opposite is true. The French audience is comfortable with this sort of thing, indeed they seem to expect and enjoy it, they don't have the expectation that the great man is going to engage with them on their own everyday level, and indeed in the presence of someone like Bresson the great artists, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Bach, Mozart, various 18th century painters, etc, come alive and are important again as they were when I was a student, the way they could always be I sense if I had found the right working or social path. But I rarely have the kind of encounters anymore that bring me back to that state of mind.

Despite including the book among its "Library of Literary Treasures" the IWE introduction is fairly lukewarm. "It has been criticized as much too long," they say, "and it is very long; and also the good poetry is often lost between unadorned narrative that should be in prose and is forced into metrical verses." I felt something of this, though given that I am largely out of the practice of reading long stretches of blank verse and often found myself getting tired quickly unless I had just awakened from a nap, I thought it might just be me. The versification and poetic sensibility are legitimately strong for the most part, and easily justify the use of the form. The story is both slight and implausible, and while it is not what one would specifically read the poem for, it does put an unnecessary strain on the verses at times.

I am going to try not to copy too many verses here since they don't make for exciting blog posts, but I always want to note a couple of samples to remember the books by. There were several passages of a feminist nature, decrying the expectations for a woman's life in Victorian England, the regard in which their intellectual and artistic abilities were generally held, etc, but there wasn't any brief set of lines on those topics that I especially liked. I do like her descriptions of the English landscape, indeed I admired these in several places.

(Book I, ll. 1079-84)

"And view the ground's most gentle dimplement,

(As if God's finger did not touch but press

In making England) such an up and down

Of verdure,--nothing too much up or down,

A ripple of land; such little hills, the sky

Can stoop to tenderly and the wheatfields climb;"

(II, 109-114) Aurora, defending her desire to write poetry to a skeptical man (and her eventual husband)

"...I perceive

The headache is too noble for my sex.

You think the heartache would sound decenter,

Since that's the woman's special, proper ache,

And altogether tolerable, except

To a woman."

(II, 218-25) The men in this time were of course pretty scornful of women's claims to any kind of cerebral equality or even pretension. In any event they would always have their say.

"Therefore this same world

Uncomprehended by you, must remain

Uninfluenced by you.--Women as you are,

Mere women, personal and passionate,

You give us doating mothers, and perfect wives,

Sublime Madonnas, and enduring saints!

We get no Christ from you,--and verily

We shall not get a poet, in my mind."

(II, 901-7) Back to some more sublime nature poetry

"The hidden farms among the hills breathed straight

Their smoke toward heaven, the lime-tree scarcely stirred

Beneath the blue weight of the cloudless sky,

Though still the July air came floating through

The woodbine at my window, in and out,

With touches of the outdoor country-news

for a bending forehead."

(II, 991)

"Dear Romney, need we chronicle the pence?"

I regarded this as a humorous example of the author's poetic sensibility.

(III, 161-2)

"Three years I lived and worked. Get leave to work

In this world--'tis the best you get at all."

Evidence of the Carlyle influence. I should note that the poem does engage at some length with the horrible conditions of the working poor and the outright indigent, and with socialistic ideas.

(IV, 434-6)

"How strange his good-night sounded,--like good-night

Beside a deathbed, where the morrow's sun

Is sure to come too late for more good-days:"

I like these three little lines. Only a few more to go.

(VII, 224-7)

"The world's male chivalry has perished out,

But women are knights-errant to the last:

And if Cervantes had been Shakspeare too,

He had made his Don a Donna."

(VII, 1211-14) Sadly this applies all too fittingly to me

"...I marvel, people choose

To stand stock-still like fakirs, till the moss

Grows on them, and they cry out, self-admired,

`How verdant, and how virtuous!'"

I read this modern Norton Critical Edition of the book, since the only older hardback copies of it I could find were from the actual 1800s, which don't make for good reading copies. I do like the layout and the notes in the Norton Books, I have owned both their English and American literature anthologies for 20 years and always go to them first for poems especially if they have what I need. I must confess though when I got to the end I didn't have it in me to read through any of the 200 plus pages of critical essays.

(VIII, 677-79)

"Because the First has proved inadequate,

However we talk bigly of His work,

And piously of His person."

Is the president vindicated by the appearance of a word he was ridiculed for using in the work of a fairly major poet?

(VIII, 829-32) The perception of women having a "talking versus doing" problem when it comes to achieving great accomplishments. Some are insistent that this remains the case today, though I cannot claim to hold this opinion with any confidence.

"By speaking we prove only we can speak,

Which he, the man here, never doubted. What

He doubts is, whether we can do the thing

With decent grace we've not yet done at all."

That is enough, I think.

The Challenge

After a string of lackluster challenges, the recap of this poem produced a large and varied field of contenders, with the qualifying cutoff at a fairly high 45. Among the interesting and notable books that failed to even make the tournament were Flush by Virginia Woolf (36), Eve's Hollywood by Eve Babitz (23), and Gigi by Colette (a mere 10).

1, Erin Morgenstern--The Night Circus.......................................................................6,120

2. Jim Butcher--Skin Game..........................................................................................3,610

3. Jim Butcher--The Aeronaut's Windlass....................................................................1,604

4. Tan Twan Eng--The Gift of Rain.................................................................................751

5. Jim Butcher--Furies of Calderon.................................................................................659

6. Sinclair Lewis--It Can't Happen Here.........................................................................620

7. Lisa Jacobsen--100 Ways to Love Your Husband........................................................340

8. Karl Rove--Courage and Consequence.......................................................................256

9. Willard (movie--2003).................................................................................................193

10. Charlaine Harris--Bone to Pick..................................................................................174

11. Matthew L. Jacobsen--100 Ways to Love Your Wife...................................................155

12. Charlaine Harris--Last Scene Alive............................................................................119

13. T. S. Eliot--The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock..........................................................83

14. Elizabeth Barrett Browning--Sonnets From the Portuguese........................................53

15. James Robert Parish--It's Good to be the King.............................................................50

16. Casese Quien Pueda (movie)........................................................................................45

Round of 16

#16 Casese Quien Pueda over #1 Morgenstern

I had missed the publication and apparent success of this runaway #1 seed, which dates to 2010. Normally such a book would easily be able to put away a movie, even a sexy-looking foreign one like Casese Quien Pueda appears to be, but the film had an upset allotted to it, which it takes here.

#15 Parish over #2 Butcher

The Parish book is a biography of Mel Brooks. I don't know who Jim Butcher is, but he appears to be some kind of science fiction/adventure writer, which sort of thing I have not found to my taste.

#14 Barrett Browning over #3 Butcher

While I am not sure I am ready for more Elizabeth Barrett Browning right away, she has to get the win here.

#4 Eng over #13 Eliot

Not that I don't love Prufrock, which I have of course read several times, and even recall a few classic lines from, but the Eng looks something like a worthy book and the challenge is supposed to be to some extent a departure from my comfort zone (though the classics are still allowed to win over books I really don't want to read).

#12 Harris over #5 Butcher

Both genre books. Harris is 200 pages shorter.

#6 Lewis over #11 M. Jacobsen

It Can't Happen Here seems to be the Lewis book that it most read nowadays, due to its popular subject matter, though my impression is that it was not considered one of his major works in his lifetime. I wrote admiringly about Arrowsmith here a few months back. Jacobsen, in addition to tallying less than half as many points as his wife for his mushy self-help book, is not acknowledged as a legitimate author by the library community, as not one of these institutions carries a copy of his book.

#10 Harris over #7 L. Jacobsen

Same story for the other Jacobsen.

#8 Rove over #9 Willard

I know, giving a win to Karl Rove is difficult, but I must try to set personal feelings of a non-literary nature aside in running this competition. Willard is a strange-looking movie starring the famous eccentric Crispin Glover, who since his famous turn as McFly in the original Back to the Future movie, has sworn off taking roles in anything that would be appealing to normal people.

Elite 8

#4 Eng over #16 Casese Quien Pueda

#15 Parish over #6 Lewis

The Lewis book is rather long for a Challenge book (458 pages).

#14 Barrett Browning over #8 Rove

#10 Harris (Bone to Pick) over #12 Harris (Last Scene Alive)

Final Four

#15 Parish over #4 Eng

Eng is also a little longer than is ideal for this competition (435 pages).

#10 Harris over #14 Barrett Browning

While it's another matchup EBB should have handled easily, she falls victim to the upset curse.

Championship

#10 Harris over #15 Parish

Controversial, and a mystery about a female librarian is not my usual fare. However it has a lot of momentum in the tournament, it is pretty short, and I think I am at a spot in the program where it wouldn't hurt to stick in a lighter reading for a couple of weeks to sharpen my concentration on the literature I am still taking on elsewhere.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)