A few months back, a prominent culture blogger (whose work I generally like) wrote a little piece, which has remained with me, breaking down some of the differences between that element of society which is creative and that which is not. While obviously the main premise could be argued against on the grounds that many highly creative and prolific people have managed to reproduce and a few have even forged fairly close relationships with their offspring, it is on the whole accurate as far as the masses of would-be artistic types who did not have what it took to avoid falling into the snares of conventional bourgeois life, myself sadly included among these. This demographic makes for a fat target in most areas where delusions of cultural dynamism or meaningful personal achievement are concerned, but its absurdities are not usually delineated so incisively, and with a clarity that even it can understand, as in the above article.

While of course the underlying theme of this article is my sense of my own personal failure, or at least my innate non-artisticness, which while little more than a vague death-feeling that has descended upon my consciousness, is the only one of these feelings I can confidently identify, it is my (probably vain) hope that I will not dwell on myself too much. Suffice it to say, I have not done anything remotely artistic in years--not so much as redecorating a room (or even envisioning doing so), or designing a bulletin board, or displaying the slightest hint of flair either in dress, conversation or movement. My mental life has been completely aimless for years, and I have not felt an energy or passion or any sensation apart from worry about money in so long that I am nearly at a loss to speculate on what the source of any former interest I ever had in any area of life ever was. I am an absolute vegetable. I am dead to everything that might bring flair or spice into my life.

I was reading the other day about the expat American theater scene in Amsterdam--their shows mostly center around the issues of tourists, culture clash, progressive politics, etc. However the shows are well enough attended that one of these particular troupes has been there since the 90s, apparently able to support themselves and lead the bohemian life in this city of art and bars and coffee houses and adventure (read: sex)--seeking tourists from all over the world. They have at the very least averted one of the great soul-killing dilemmas which faces modern man, that of having to live within the corporate system and culture while being at the same time temperamentally and intellectually estranged from it--this latter ensuring that you will not even attain to the consolations of status, superior income and advancement in that system.

I don't believe that marriage and children in themselves are the problem, in my case especially. I was not married until I was 27 and I did not have my first child until I was 32. If I was ever going to do anything substantial, creatively or otherwise, it ought to have been long underway by that second date especially. The problem is my brain and my enthusiasm for day to day life and what has happened to them. Perhaps I am starting to get worn down with having very young children. There has been at least one person in my household in diapers constantly since 2002 (and this will continue to be so probably until early in 2014). The last child won't be in all day school until 2017, at which time I will be 47 years old! My two oldest are currently in 4th and 5th grade. If I had stopped there, like most people do, their pre-school years would seem a mere blip of time, years in the past now. They would be halfway to college age--of course they still are, but as things stand now, we will probably be desperate for them to go because we'll need the space. But everything would be so quiet and empty without all of the little ones, and I'm sure I would not be any smarter or more creative, or even richer. There has been a small spate of articles lately (this week, actually) about the travails of 'older' parents--most of the writers are about my age--a few of which offer laments that perhaps they should have had children earlier. I take some consolation from the fact that I seem to be holding up pretty well physically in comparison to some of the other parents. While my energy for literature is diminished I have much more of it for taking care of children than I would have had at twenty-five, at which time I would really have felt imposed upon. 'Chasing them around' causes me little trouble. It is true I am always tired, and I never get enough sleep, but not much more than I was ten years ago. One of the main problems of having many children is that nearly every day you are roused out of bed not merely before you are ready but by someone screaming or jumping on you or demanding something, which is quite disorienting and stressful. I did really notice the effect this had on my mood until one day last week, doubtless as a result of the days being short and the sun rising fairly late, I actually woke up to silence, and was able to collect my thoughts for a few minutes before I sat up and started pulling my clothes, and it was remarkable how this calm awakening effected my mood the rest of the morning. But literally, I have woken up in this kind of quiet state without any kind of outside prompting maybe five times in the last ten years.

But I am supposed to be writing about the life of the real artist here.

It is not what I have just written, or at least that is not its essence.

I gather from the article that for the urban creative type, sex, and especially new sexual adventures, remain very real aspects of life until the brink of old age. I still think about having sex the overwhelming majority of every day but over time it ceases to be real or to seem possible, for the likes of you anyway, in the mainstream world.

I would be most happy in any of my children grew up to have legitimate bohemian artist souls and live accordingly; I still imagine it as the highest kind of life, the great illusion, because real artistic skills and thought processes, and access to a society of people of similar qualities, make you the most alive, the most engaged with life, that you can be. Nearly all that is worthwhile in experience, social, sexual, intellectual, is open to you...

I cannot expand further at this time. I am too exhausted, and my concentration is absolutely shot.

It all comes back to the American in Paris thing though, the fantasy, and how the fantasy is real to those who understand it, and in most important ways is more real than whatever it is he is supposed at any given time to understand as real.

Wednesday, December 12, 2012

Monday, November 12, 2012

Anne Bronte

"Anne was the least-read and -admired of the remarkable Bronte sisters, but the fact remains that she was one of the remarkable Bronte sisters and her novels are brilliant in spots, competent elsewhere. Agnes Grey...published in 1847 (ed: author age--27)...has a large autobiographical background of course: Anne, like her heroine Agnes, was a poor clergyman's daughter, was docile to a fault, and worked as a governess. But unlike the novel, Anne's life had no happy ending--not even in a literary sense, for Agnes Grey was never well received during her lifetime...Agnes Grey is quite a short novel, under 150,000 words."--I.W.E.

The other novel of Anne Bronte (who died at age 29), The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, was not chosen for the I.W.E. Hall of Fame, though currently it appears to be regarded with at least equal esteem to Agnes Grey.

This is not my copy of the book--I haven't read it--but I have a lot of these 1995-2003 or so era Penguin Classics with which it would be at home.

The Brontes are such central and beloved figures in the popular history of English literature that I feel I have little enough to contribute to the general understanding where they are concerned, and as I also prefer to wait to write about Emily and Charlotte, whom I have read and am thus at least somewhat familiar with, when their turns on the list come up, there seems little to say about Anne. I checked Winnifred Gerin's dusty 1959 biography of her out the State Library (the first person to do so since 1984) looking for any of the interesting anecdotes that are sometimes found in such works, but the book tends to be both idolatrous towards the whole family and completely pre-60s middlebrow in outlook (i.e., no discernible humor or even speculation regarding sensualism) that I could find nothing in it worth using. I don't believe the family could really have been that boring, though maybe Anne was.

One does wonder what possessed these creatures in their isolation and apparently innocent--especially sexually so--youth to set for themselves the task of 'instructing' the nation through the writing of novels; not to mention largely succeeding in doing so. Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights are both secure among the top 100 most read and probably most esteemed English novels, perhaps among the top 50. Our current society of 300 million people, with its thousand universities and hundreds of graduate level creative writing programs and publishing houses turning out 6,000 novels a year and constant mass traveling to every corner of the earth has little hope of ever producing two such books, which was the work of a single fairly poor and informally educated household in rural Yorkshire in the 1840s. They also of course doubtless encourage the idea that anybody can become an author, however provincial their background or paltry their connections to the literary world, which I guess is bad for society, since most people who aspire to a literary career seem to be very poor at assessing their literary talents, as well as figuring out anything they might actually be able to perform usefully and competently and earn an income from. But let us not forget that mediocrity and failure, the common lot, are dreary and neverending, and achievement and success, even posthumous, are inspiring to those who come after. So I hope the Brontes do not fade into oblivion as irrelevant to the new age of man yet.

Anne Bronte was born in 1820, the youngest of a family of six and the fifth daughter, in the same house as her famous sisters, 74 High Street in Thornton, West Yorkshire. Anne only lived here for a few months before the family moved to nearby Haworth. The building still stands, though altered over the years, and is commemorated by a plaque. The house was actually acquired by devotees of the Brontes and turned into a museum from the late 1990s until 2007, but they were unable to keep it open and it has reverted back to a private residence again. The train station in Thornton closed in 1955. If you are traveling by rail you will have to take the bus the last few miles from Bradford.

The Bronte Parsonage Museum in Haworth, according to the 1996 edition of Lonely Planet Britain (I don't care for their guidebooks since about 2000, but I fear that is because the world has changed and I have not been able to change enough with it), 'rivals Stratford-upon-Avon as the most important literary shrine in England'. They were enthusiastic about the museum and indeed the whole town, which was far from a sure thing with their hip young travelers at the time--this was still kind of back in the young Justine Shapiro era, I believe. Among other things you could, and presumably still can, see "one of (Charlotte's) dresses and a pair of her tiny shoes." I always had something of a crush on Charlotte, among all the Victorian lady writers.

The nearest real train station to Haworth is in Keighley, from which during the week you would have to take the bus. However on the weekends there is a tourist line running trips via steam engine on the hour between the two towns which is at least an option for the non-driver.

While most of the family, including the two more famous sisters, are buried in the churchyard adjacent to Haworth Parsonage, Anne died at the formerly fashionable and now faded North Yorkshire seaside resort of Scarborough, and was buried in the churchyard of St Mary's Church there, near both the ruins of the ancient castle and the sea. The town is the terminus of several train lines and has regular direct service to York, Leeds, Manchester and Liverpool.

Monday, October 15, 2012

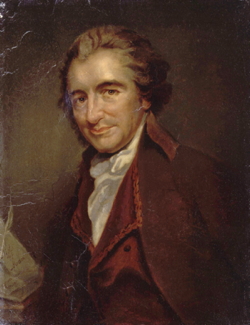

Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine is a fun guy to have on the list. Not only does he remain very dear to Americans of a certain imperfectly balanced tilt, but the tourist sites associated with him are in good locations, and have in themselves been the source of considerable wildness. These are welcome qualities in the ordinarily dry world of literary tourism.

Just one of Thomas Paine's celebrated works got officially tapped for this roll call of immortals--in my memory I thought two or three had made the cut--the 1795 tour de force The Age of Reason (author age at publication: 58):

"Thomas Paine wrote Age of Reason in 1793 and 1794, when he was France participating in the French Revolution (and considered himself a citizen of France). The book is of historical importance because it created such a furor, especially in the United States, where it was published. Even today there will be those who disapprove its being summarized here. At the time, Age of Reason was called 'atheistic'; but this was a misuse of the word, because in the book Paine affirms belief in one God and in human immortality. Rather than being an attack on religion, the book is an attack on literal interpretation of the Bible, specifically the Authorized ('King James') version."

This seems to have been the standard mid-century opinion. The introduction to Age of Reason in the volume pictured below also makes the argument that Paine was completely misunderstood and was in fact a deeply religious man. I have not read this particular work, so I cannot comment on it specifically, however I have read the Rights of Man and my impression, and the one I would imagine most modern readers would get from that book is not of a deeply religious man, if they even had a conception of what that means. He was doubtless a man possessed of extraordinary animal spirits and a tireless capacity for outrage and antagonizing those in authority who were offensive to him, which temperament, as William James for one observed so lucidly in his Varieties of Religious Experience, is frequently more conducive to an intense spiritual life than that of what he refers to as the 'ordinary sluggard'. Paine's spirituality, I think it is safe to say, was not characteristic of the school known as Moralistic Therapeutic Deism, the squishy, inoffensive, nondemanding spiritual-but-not-religious creed which is viewed as the predominant (and false) understanding of the spiritual life among our modern day educated population.

My Thomas Paine book. Another author, another Modern Library edition--it won't be like this all the way through, though the series does match up pretty well with the list we are currently working on. This edition, from 1945, is a rather odd one, in that in addition to the man's own famous works--Common Sense, The Crisis Papers, Rights of Man, The Age of Reason, and two letters to George Washington--there is a two-page wrap-up entitled "Tom Paine: an Estimate" which is written in an ebullient, boosterish, unmeasured tone, and a 300-page novel of what looks to be uncertain literary merit about Thomas Paine's life by the heretofore unknown to me Howard Fast.

My hastily written summary of The Rights of Man, dated March 7 of this very year, 2012, is enthusiastic. 'Invigorating stuff. Man had a genius for contrariety, though perhaps overly optimistic re. democracy. Love reading him though. Makes one feel vital, alive.' You get the idea. I have often thought, if there is any epoch of history from which I wish there were more literary works, it would be the early years of the American republic, around 1780 to 1810/1820 or so. The optimism and energy and general personality of the free portion at least of the population of the new nation at that time seem to have been extreme, unique, and remarkably effective by historical standards in that period. For writings from the time which capture this spirit you have Paine, you have the Federalist Papers, which can be an exciting read in the right frame of mind, Jefferson's various writings, such speeches and anecdotes of George Washington that were recorded, the Constitution, Benjamin Franklin's Autobiography, which I know was written before the revolution but I think still fits in with this theme, Lewis & Clark's Journal: I want more stuff in this mode, or at least a greater sense of its carrying weight in the culture, because those years are essential to whatever this country is now, and in many instances and aspects in a more positive sense than any comparable period of time.

His prediction regarding the potential imminent abolition of war in Europe when the intrigue of royal courts should be replaced by democratic government was somewhat premature (especially as the book was published in 1791).

Paine is against taxes.

He swats his philosophical enemy Edmund Burke around so much that at first you wonder why Burke is still relatively respected today, and at second how much Paine is willfully misinterpreting and misrepresenting the crux of Burke's arguments.

'Man has no authority over posterity in matters of personal right; and, therefore, no man or body of men had, or can have, a right to set up hereditary Government.' This point is hammered home a lot. Paine loathed hereditary privilege with a righteous fervor that at least as far as its effective expression goes, seems to be absent from our current political discourse.

His book over-romanticizes the representative system. He is blind to its defects.

"...the routine of office is always regulated to such a general standard of abilities as to be within the compass of numbers in every country to perform, and therefore cannot merit very extraordinary recompence." Evidently this is no longer the case.

"We already see an alteration in the the national disposition of England and France towards each other..." Maybe not. "That spirit of jealousy and ferocity, which the Governments of the two countries inspired, and which they rendered subservient to the purpose of taxation, is now yielding to the dictates of reason, interest, and humanity." International strife is just a masquerade to bolster taxation? Paine wasn't much of an economist either, at least of the type that is in fashion nowadays. He considered domestic trade preferable to foreign because only half of the benefits rested with the Nation. Ha!

"Yet from such a beginning, and with all the inconvenience of early life against me, I am proud to say that with a perseverence undismayed by difficulties, a disinterestedness that compelled respect, I have not only contributed to raise a new empire in the world, founded on a new system of Government, but I have arrived at an eminence in political literature, the most difficult of all lines to succeed and excel in, which Aristocracy with all its aids has not been able to reach or to rival." This is an excellent distillation of the revolutionary mentality, which I admire by the way, even though I am nitpicking at some of his arguments. Multitudes of eminently qualified people in his own day took apart his arguments much more harshly that I have and Thomas Paine came back firing with twice as much venom in every instance, absolutely convinced of his righteousness and the evil of his enemies. That is the revolutionary spirit.

Illustration of how the world has changed since the 1790s: "To form some judgment of the number of those above fifty years of age, I have several times counted the persons I met in the streets of London, men, women, and children, and have generally found that the average is about one in sixteen or seventeen." This is probably not a precise calculation, but I do often think that we don't realize how skewed towards the middle-aged and elderly the population of our current society is compared to almost all of human history and the kinds of odd effects this dynamic is producing on us.

Paine does seem to be in favor of taxation/redistribution as long as it is on his terms. Defunding the Duke of Richmond's pension and slapping a tax on 'luxuries' as defined by himself, such as idle land on the estate of an aristocrat that is potentially a common good. We have been unsure of both the desirability and justness of this type of action over the last 30 years, but I'm pretty sure this sentiment is going to come back, in the United States anyway, especially when the generation that is now under 35 or so begins to come into power. The timing of this for me will probably work out that the day after I finally attain the raise and other assets to plausibly be able to call myself prosperous, be able to pay for my children's school, and so on, the tax rate will be raised to 75% or something, kind of like in the Bohumil Hrabal book I Served the King of England in which the day after the main character, after decades of struggle, becomes an official millionaire, the communists overthrow the government and declare all millionaires criminals. But I actually do want to live in the best possible society, and I don't think the current economic structure is very conducive to that at all, so I probably wouldn't be all that upset if it happened anyway.

The 'estimate' of our author in my book makes a lot of claims about the man that I am not entirely convinced of as yet, but this paragraph strikes as hitting somewhat close to the truth:

"Paine has that rare historical distinction of being unique; there are no comparisons, because there has been no one, before him or since, quite like him. He had the fortune to arrive in the right place at the right time, and once there, he accepted history instead of attempting to avoid it."

Paine was born at Thetford in Norfolk in England. My 1970s era reference book gives the site of the birth as the garden of Grey Gables in White Hart Street. The site is evidently now occupied, conveniently, by the Thomas Paine Hotel, and the address is 6 Thomas Paine Avenue. This indicates to me that our guy is not forgotten. Thetford has a train station, and is on several lines originating in Norwich, and connects with Cambridge, Sheffield, Manchester and Liverpool, though there appears to be no direct service with London (change at Cambridge).

Paine lived briefly at Sandwich, in Kent, when he was 22. He was married there and set up in business as a staymaker, which seems to be an old term for a corset-maker. His business failed and shortly afterwards his wife died, at which time he was still just 23. His residence at 20 New Street still stands and is preserved as a rental cottage. Sandwich appears to be an extremely well-preserved and hopelessly quaint medieval town. Sandwich God bless them has rail service from Ramsgate and London (mainly Charing Cross, but also 3 trains a day to St Pancras).

The main Thomas Paine attraction in the United States is his cottage and adjoining museum in New Rochelle, New York, which is turning out to be quite a literary place (see Robert E Sherwood). I am thrilled to see that this complex appears to be back in operation as it was shut down for a time in 2009 as a result of, among other things, the selling off of 'priceless artifacts and documents' by the former president of the board--who had originally been hired as a janitor and lived rent-free in an apartment above the museum. I bet this kind of stuff does not go on at the Jane Austen museum. I would be keen to go to that Swing Dance Party that is being held at the museum on the evening of December 7, though I am not sure what swing dancing has to do exactly with Thomas Paine. The point is, it doesn't matter.

I have always liked the Westchester suburbs of New York City, and I pass through there several times a year on various journeys south. I frequently stop to eat in this area. It still retains a lot of that old New York atmosphere.

Here is a little video of the site:

Thomas Paine is also too cool to have his remains deposited in an identifiable place. He did once, on the grounds of the farm where his museum now is, and the spot is marked by a nice plaque. However:

"When William Cobbett returned in November 1819 from his second visit to America he caused great excitement at the Custom House by having the bones of Tom Paine in his luggage. He had exhumed these from a patch of unconsecrated ground near New York, where Paine had been buried (1809), with the intention, advertised in the Political Register, of raising money to build a mausoleum to house them in England as an object of pilgrimage, but instead of subscriptions he received only ridicule, as in Byron's lines:

'In digging up your bones, Tom Paine,/Will Cobbett has done well;/You visit him on earth again,/He'll visit you in hell.'"--The Oxford Literary Guide to the British Isles.

No one seems to know definitively what became of the bones after that.

Besides the enormous quantity of literary scholarship and commentary devoted to the works of this most fascinating founding father, there are many videos discussing his work on Youtube by well-known and little-known commentators alike--there appear to be several hours worth of Christopher Hitchens interviews alone which are solely devoted to talking about Paine. I have decided not to put any of them on here because they are all quite long and I don't have time to listen to them at the moment. Doubtless anyone who wants to find them can easily do so.

Thomas Paine's current-day fans seem to be on the whole as angry and impetuous as he was, perhaps especially towards each other. Here is a former trustee of the now-closed Thomas Paine museum (not to be confused with the cottage above, though it sits, shuttered, a couple of hundred yards down the street from it) breaking down the myriad reasons why he won't be attending this year's scholarly conference on our author in New Rochelle. Here, a no-nonsense visitor from Seattle concisely lays out all that is lacking at the mess that is the New Rochelle memorial from both the historical and the touristic point of view. Pretty damning review, though I still think it would be worth stopping by sometime if I were in the area. For me, even just a half hour walking around the abandoned grounds and reading the uninspired monuments would be a happy respite from the monotony and moment to moment insignificance of ordinary life.

Wednesday, October 3, 2012

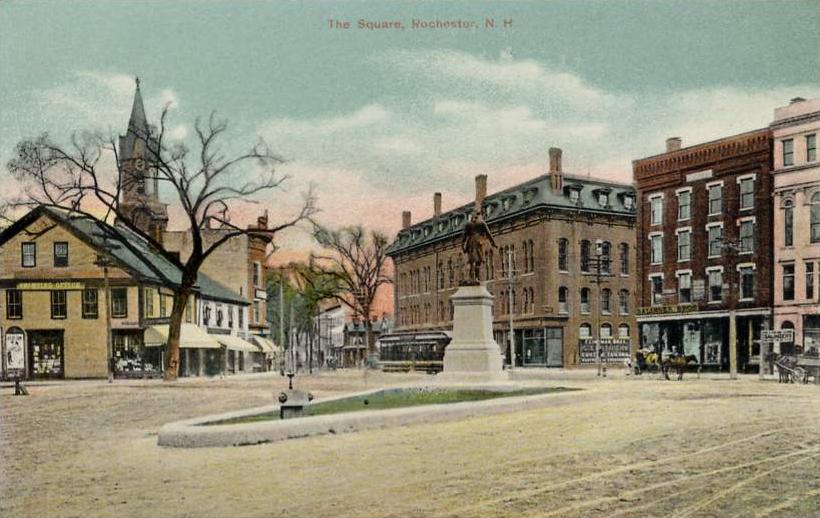

Walking Distance to Towns Containing Unseen Literary Sights From My House (Within 250 Miles)

1. Rochester, New Hampshire...................38

2. Methuen, Massachusetts........................45

3. South Berwick, Maine...........................47

4. Andover, Massachusetts...…………….50.5

5. Plainfield, New Hampshire...................51

6. Windsor, Vermont.................................52

7. Portsmouth, New Hampshire...………..53

8. Newburyport, Massachusetts.................54

9. Concord, Massachusetts.......................63

10. Kennebunk, Maine...............................65

11. Clinton, Massachusetts........................70

Kennebunkport, Maine..........................70

13. Cambridge, Massachusetts..................71

14. Newtonville, Massachusetts...……….72

15. Boston, Massachusetts.........................73

Newton, Massachusetts.......................73

17. Brookline, Massachusetts....................74

18. Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts..............75

19. Quincy, Massachusetts........................ 81

20. Worcester, Massachusetts....................82

21. Portland, Maine....................................88

22. Halifax, Massachusetts......................103

23. Duxbury, Massachusetts....................106

24. Plymouth, Massachusetts...................110

25. Chicopee, Massachusetts....................112

Providence, Rhode Island...................112

27. Brunswick, Maine...…………………113

28. Williamstown, Massachusetts............114

29. Fort Edward, New York.....................127

30. Lenox, Massachusetts.........................133

31. Lake George, New York.....................135

Waterford, New York.........................135

33. Hartford, Connecticut...……………..138

Troy, New York..................................138

35. Menands, New York...........................141

36. Austerlitz, New York..........................144

37. Matunuck, Rhode Island.....................148

38. Vineyard Haven, Massachusetts.........149

39. Mystic, Connecticut............................151

Stonington, Connecticut.....................151

41. Fairfield, Vermont..............................152

42. New London, Connecticut..................153

Tisbury, Massachusetts.......................153

Torrington, Connecticut......................153

45. Litchfield, Connecticut...…………….158

46. Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts......160

47. Rockland, Maine.................................164

48. Hamden, Connecticut..........................170

49. North Elba, New York.........................174

50. New Haven, Connecticut.....................175

Truro, Massachusetts............................175

52. Saranac Lake, New York.....................182

53. Tannersville, New York......................184

54. Bridgehampton, New York.................191

55. Hyde Park, New York.........................193

56. East Hampton, New York...................194

57. Southampton, New York.....................196

58. Weston, Connecticut...........................201

59. Cooperstown, New York.....................206

60. New Canaan, Connecticut...................210

61. Montreal, Quebec................................216

62. Lake Ronkonkoma, New York............219

63. Montgomery, New York...…………...222

64. Valhalla, New York.............................224

65. Sleepy Hollow, New York..................226

66. Haverstraw, New York........................228

67. Hartsdale, NY......................................230

Tarrytown, NY....................................230

69. Hastings-on-Hudson, New York.........232

New Rochelle, New York...................232

Rockland, New York.......................... 232

72. Huntington Station, New York............233

73. Nyack, New York...............................236

74. East Farmingdale, New York..............237

75. Bronx, NY...........................................238

76. Greenvale, New York..........................244

77. New York, NY....................................248

78. Maspeth, New York............................249

79. Ridgewood, New York........................250

2. Methuen, Massachusetts........................45

3. South Berwick, Maine...........................47

4. Andover, Massachusetts...…………….50.5

5. Plainfield, New Hampshire...................51

6. Windsor, Vermont.................................52

7. Portsmouth, New Hampshire...………..53

8. Newburyport, Massachusetts.................54

9. Concord, Massachusetts.......................63

10. Kennebunk, Maine...............................65

11. Clinton, Massachusetts........................70

Kennebunkport, Maine..........................70

13. Cambridge, Massachusetts..................71

14. Newtonville, Massachusetts...……….72

15. Boston, Massachusetts.........................73

Newton, Massachusetts.......................73

17. Brookline, Massachusetts....................74

18. Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts..............75

19. Quincy, Massachusetts........................ 81

20. Worcester, Massachusetts....................82

21. Portland, Maine....................................88

22. Halifax, Massachusetts......................103

23. Duxbury, Massachusetts....................106

24. Plymouth, Massachusetts...................110

25. Chicopee, Massachusetts....................112

Providence, Rhode Island...................112

27. Brunswick, Maine...…………………113

28. Williamstown, Massachusetts............114

29. Fort Edward, New York.....................127

30. Lenox, Massachusetts.........................133

31. Lake George, New York.....................135

Waterford, New York.........................135

33. Hartford, Connecticut...……………..138

Troy, New York..................................138

35. Menands, New York...........................141

36. Austerlitz, New York..........................144

37. Matunuck, Rhode Island.....................148

38. Vineyard Haven, Massachusetts.........149

39. Mystic, Connecticut............................151

Stonington, Connecticut.....................151

41. Fairfield, Vermont..............................152

42. New London, Connecticut..................153

Tisbury, Massachusetts.......................153

Torrington, Connecticut......................153

45. Litchfield, Connecticut...…………….158

46. Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts......160

47. Rockland, Maine.................................164

48. Hamden, Connecticut..........................170

49. North Elba, New York.........................174

50. New Haven, Connecticut.....................175

Truro, Massachusetts............................175

52. Saranac Lake, New York.....................182

53. Tannersville, New York......................184

54. Bridgehampton, New York.................191

55. Hyde Park, New York.........................193

56. East Hampton, New York...................194

57. Southampton, New York.....................196

58. Weston, Connecticut...........................201

59. Cooperstown, New York.....................206

60. New Canaan, Connecticut...................210

61. Montreal, Quebec................................216

62. Lake Ronkonkoma, New York............219

63. Montgomery, New York...…………...222

64. Valhalla, New York.............................224

65. Sleepy Hollow, New York..................226

66. Haverstraw, New York........................228

67. Hartsdale, NY......................................230

Tarrytown, NY....................................230

69. Hastings-on-Hudson, New York.........232

New Rochelle, New York...................232

Rockland, New York.......................... 232

72. Huntington Station, New York............233

73. Nyack, New York...............................236

74. East Farmingdale, New York..............237

75. Bronx, NY...........................................238

76. Greenvale, New York..........................244

77. New York, NY....................................248

78. Maspeth, New York............................249

79. Ridgewood, New York........................250

Sunday, September 30, 2012

Edith Wharton

Edith Wharton in 1880, aged 18 years.

Edith Wharton made the list twice, for Ethan Frome (1911) and The Age of Innocence (1920). The author's ages at the publications of these books were 49 and 58, which is a late age for a famous writer to turn out her most celebrated works. The IWE blurb on Frome is not one of their better-written efforts:

"It may have been only surprise that Edith Wharton, whose life was one of wealth in New York's excessively formal society, could write so well about poverty and simplicity on a New England farm where only poverty and simplicity were known; but for whatever reason, critics acclaimed this novel when it was published and have generally rated it her best work. That is a high rating, Edith Wharton was one of the most important American novelists of her times."

The introduction to Innocence appears to take its inspiration from the popular image of Wharton as an unsmiling, frigidly correct Henry James-like snob, which persona was not at the height of its esteem in the middle of the last century:

"Edith Wharton wrote of life as she knew it personally--the life of rich and socially prominent families in New York City at the turn of the 20th century. Her depiction of the manners and mores of the times is accurate, revealing, and often exasperating to those whose lives began later than the lives of the characters in her books...(Innocence) is not a light novel and demands a modicum of understanding and sympathy from the reader--but it is an excellent portrait of life and persons in its time."

The copy of The Age of Innocence pictured above is the only stand alone Edith Wharton book I own. I have not yet read it, which is unusual with me in that I usually only buy books I intend to read right away. However the library in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, which is where most of my family lived, and still lives, and where I lived on and off myself for several years earlier in my life, used to have great book sales in its basement, lots of Modern Library editions for a quarter or 50 cents, which on the particular day I got this must have seemed too good to pass up. This is going to come up on my current reading list, which in November I will have been following for 18 years, at some point--I have seen it--though it does not look like that point is going to be anytime in the next five years, at least. I did read Ethan Frome sometime in late 2010. I do not own a separate copy of it because being quite short it is included in its entirety in The Norton Anthology of American Literature, where it only takes up about 60 pages, and I read it there. I thought it was a good book, well worth reading, especially perhaps if you are familiar with the part of the world where it is set, in which the landscape and basic village geography are in many places even today not much different from what is depicted in the novel (Western Massachusetts specifically, but much of Vermont and Northwestern Connecticut also fit this profile). The toll that the climate and isolation, especially in the years when you get a traditional New England winter (i.e., not so much this past year), takes subtly on your ability to project any warmth or sensuality towards other people over the course of several decades, which is still a real phenomenon, is illustrated as starkly and economically in Ethan Frome as I have found it anywhere, at least since I have been able to note the same process happening to myself. I only made a few little notations in the book while I was reading it, but I will reproduce a few of them here to provide a fuller impression of my feelings about the book (because after spending twenty fruitless years attempting to understand the world by means of thinking, this blog is going to be about the only thing that ever existed for me, my feelings).

The description of the vicissitudes of the male lover's (Ethan's) inarticulate romantic feelings are quite good. From Chapter V:

"Her tone was so sweet that he took the pipe from his mouth and drew his chair up to the table. Leaning forward, he touched the farther end of the strip of brown stuff that she was hemming. 'Say Matt,' he began with a smile, 'what do you think I saw under the Varnum spruces, coming along home just now? I saw a friend of yours getting kissed.'

The words had been on his tongue all the evening, but now that he had spoken them they struck him as inexpressibly vulgar and out of place."

This is pretty much my life story.

Some more description hitting painfully close to home, from Chapter VIII:

"Here he had nailed up shelves for his books...hung on the rough plaster wall an engraving of Abraham Lincoln and a calendar with 'Thoughts From the Poets,' and tried, with these meagre properties, to produce some likeness to the study of a 'minister' who had been kind to him and lent him books when he was at Worcester."

Ouch. Almost as deflating as the time my picture got a 3.41 rating on Hotornot.com. The aspirations of people like me to books and other cultural things are so humorous/absurd to people for whom the knowledge and understanding of these things is second nature. The heavy emphasis on the inarticulateness of country, or common, people in Ethan Frome is not a mere matter of the book's being 100 years old. If you ever peek into some contemporary fiction from the Ivy League/Manhattan based crowd (not that there is any great necessity to do so), the gap in literary and artistic sensibility and intelligence between people in or connected to Manhattan who care about such things and those outside that world who imagine they care about such things is still perceived to be enormous (and not, incidentally, to the denigration of the Manhattan people). How huge are these gaps, especially at the level of people who are not widely famous, and why are they thus huge? It is obviously the constant reinforcement one gets from the positive identification of oneself with the life and culture of the city and its all-conquering institutions--if one can swing the identification part in one's favor once and for all. When you are wholly outside of this, and especially outside of any scene at all reasonably approximate you can read and write and think and drink cocktails and maybe even occasionally try to hit on arty-looking girls in dingy alt-rock bars, you just can't get the reinforcement that any of it is getting you anymore, and everybody can see it in your confused and overeager demeanor.

Edith Wharton was born at 14 West 23rd Street in Manhattan in 1862. Most biographical accounts note that she was born into "Old New York"--the WASP/Dutch high society whose power and influence and numbers were diminished I guess by the floods of immigration from Eastern and Southern Europe in the latter 19th and early 20th centuries, though I thought there were a few of them still around (Aren't they the characters populating Whit Stillman movies?) The building she lived in appears to still be standing, though it has been renovated so many times that most accounts of the site describe the Wharton house as hiding within the shell of the current facade. As of 2011 a Starbucks was installed on the ground floor. This address is near 5th Avenue and Madison Square Park. The Flatiron Building, which is a favorite of mine, can't be more than a few doors away. That whole neighborhood is one of my favorite (as in top 15) in town. According to another article from 2011 a commemorative plaque is supposed to be placed on the building in honor of Edith Wharton, who was known by the delightful sobriquet of Pussy Jones (Jones was her maiden name) when she lived in the house. Subway: 23rd Street at Broadway (N & R Lines)

The great Edith Wharton-themed tourist attraction is her opulent Berkshire house The Mount, physical address 2 Plunkett Street in Lenox, Massachusetts, 5 minutes from Exit 2 off the Mass Turnpike. I am delighted to see that The Mount appears to be open again, as I remember reading a few years back that they had had to close for a time due to financial problems. I should really try to get down there and see it, though Western Mass can be surprisingly far from anywhere. The Mount is 3 hours and 15 minutes drive from my house in New Hampshire. It is even an hour and 45 minutes from our camp in Brattleboro, though that would be doable as a day trip.

Here is a 12 minute video introduction to the Mount which it looks like the stewards of the property have put out themselves. I put it up here as a resource for anybody whose interest has been roused by the tone of this or any other of my modest articles

Edith Wharton was a 1% type from birth, so it is hardly surprising that the desirable geography where she was concerned would be extended onto the grave, her interment being at the Cimitiere des Gonsards in Versailles. Actually I could be wrong about the desirability of the location, but it sounds desirable. Besides the palace, which looks to be within strolling distance of the cemetery, my impression of the modern town is that it is a prosperous, haute bourgeois locale. One could make a decent day of the visit, I should think. The cemetery is very near the Versailles-Chantiers RER station. I can already picture myself trying to buy a ticket for this station and having the attendant assure me that I really want to go to Versailles-Rive Gauche, because that is right outside the gates of the palace and is where all the tourists want to go (the line appears to split right before it comes to these stations, so getting off a station early to satisfy one's petty desire to do things the way one wants to do them is not an option). The palace is only an 18-minute walk from the Chantiers station according to Google maps anyway.

Trailer for the rarely-seen 1934 film of The Age of Innocence starring Irene Dunne. Wharton herself was still alive at this time--she died in 1937--which I thought of interest because though one always associates her with a seemingly much earlier and more remote time than the 1930s, she of course was not.

I have never much warmed to serious literary adaptations featuring A-list Hollywood stars post-1980 or so, and I have never seen the 1993 Martin Scorcese version of Innocence, but I will put a clip from it on here because it is supposed to fairly good. Also I find I miss Winona Ryder now that she isn't around much anymore. She was never much of an actress, but she was ubiquitous, or seemed to be, for a while, and she was attractive in an earnest way that being soft of heart I always found rather endearing.

There is a pretty recent movie of Ethan Frome starring another favorite Generation-X era starlet, Patricia Arquette--who didn't like her?--but I cannot find anything snippet-sized from that production that I would want to put on here. I have not seen this movie either.

My French tutor in college, the late Douglas Allanbrook, who was a composer of some renown, wrote an opera based on Ethan Frome. Excerpts here. I have not listened to much of it--the time required for even a one hour and 48 minute recording somehow seems daunting to me nowadays--but I thought I ought to include it in the catalog, for Mr Allanbrook was one of the few serious adult men who didn't openly hate me that I have had the opportunity to engage with on a day to day basis, and I am pretty confident that his work contains some merit.

Sunday, September 16, 2012

Aesop

"For so many years all fables were called 'Aesop's Fables' that none can be definitely attributed to Aesop himself, who lived early in the 6th century B.C. For literary purposes Aesopian is a better word than Aesop's and two criteria should be applied to the fables: Each must have sentient animals as characters and must lead to a 'moral' as a conclusion; and each must have been included in the collection made by Phaedrus, first-century Latin poet. This is not to say that all or even any of the fables in Phaedrus's collection were necessarily written by Aesop."--IWE World's Greatest Literature Supplement, 1958.

Main encyclopedia article on subject from the same source:

"Aesop was a writer (1) who lived 2,600 years ago in ancient Greece. His stories, called fables, were so clever and amusing that they are still read today...

...Aesop lived on Samos (2), a Greek Island in the Aegean Sea. He is said to have been a slave (2) who was freed by his master (3). The exact time or reason for his death is not known (4), but some writers of history say that he angered a mob of people in the Greek city of Delphi and they threw him over a cliff."

Here, a more up-to-date quotation from the English classical scholar Martin Litchfield West:

"The name of Aesop is as widely known as any that has come down from Graeco-Roman antiquity [yet] it is far from certain whether a historical Aesop ever existed...in the latter part of the fifth century [BC] something like a coherent Aesop legend appears, and Samos seems to be its home."

(Not my personal copy of the book. I don't have one.)

Some additional notes on the second passage above:

1. Seeing as there is considerable uncertainty as to whether "Aesop" refers to an actual person, stating that he was a writer of some kind when neither original writings attributed to him nor specific, creditable references to the existence of such writings in literary, or book, form survive, is obviously taking a bit of a liberty.

2. Most ancient sources appear to agree that the supposed Aesop lived in Samos and was a slave at some point. His place of birth on the other hand was much disputed among these same sources: claims were made more Mesembria in Thrace, the city of Sardis in Lydia (Western Asia Minor), and the country of Phrygia, which was east of Lydia, in present-day west-central Anatolia. None of these places appear to have a stronger claim than any of the others. There does seem to be some consensus, tentatively approved by modern scholarship as at least the most likely dates if there are to any at all, that Aesop would have been born around 620 B.C. and died around 564. More on this in a later note.

3. Plutarch, supposedly in the Life of Solon (I don't remember this), relates the story of Aesop's death in Delphi (more below), in which he states that Aesop was in Delphi on a diplomatic mission from King Croesus in Lydia. This is the primary source of the speculation that Aesop was at one point freed from slavery.

4. I am going to quote from the Wikipedia article re this one: "[Aesop scholar Ben Edwin] Perry...dismissed Aesop's death in Delphi as legendary; but subsequent research has established that a possible diplomatic mission for Croesus and a visit to Periander are consistent with the year of Aesop's death."

There is also a long tradition of speculation that Aesop may have been of black African origin or descent, based on descriptions and depictions of him as swarthy and of otherwise unusual appearance.

So I have never read through one of the serious compilations of Aesop's Fables. Aesop may also be the only ancient Greek content originator on this new list that was not read, and maybe even not talked about, at SJC Annapolis, though it is possible sentences or fragments from him were used as exercises in our Greek manual/textbook Still, now that we have our first ancient Greek on board the site, as well as an Italy-based ancient Roman, it is starting to really feel like the monument to lost ambitions and lost possibilities I have hoped to build up here. We still need to get some of the French in here especially, and the Germans and Russians as well, for the mausoleum of my mind to attain something like its full form, but I am beginning to see it coming into shape.

I am going to include Samos and Delphi, as the places most associated with the life and death of Aesop, on the travel list. They are places one would want to see anyway, and the excuse for giving them the official imprimatur of being on the List and therefore priority destinations, is too convenient.

1947 short film of "The Tortoise and the Hare". The matter of interest to me in this is that the movie is a Encyclopedia Britannica/University of Chicago production. I did not know that they dabbled in filmmaking at this time, and of course this is right during the period when they were cranking up all the Great Books stuff. The film has its charm, though I am surprised at how gratingly Middle American the voice of the narrator was. I was anticipating maybe one of the myriad genius European professors that were on campus at the time, or at least a top-shelf graduate student.

Main encyclopedia article on subject from the same source:

"Aesop was a writer (1) who lived 2,600 years ago in ancient Greece. His stories, called fables, were so clever and amusing that they are still read today...

...Aesop lived on Samos (2), a Greek Island in the Aegean Sea. He is said to have been a slave (2) who was freed by his master (3). The exact time or reason for his death is not known (4), but some writers of history say that he angered a mob of people in the Greek city of Delphi and they threw him over a cliff."

Here, a more up-to-date quotation from the English classical scholar Martin Litchfield West:

"The name of Aesop is as widely known as any that has come down from Graeco-Roman antiquity [yet] it is far from certain whether a historical Aesop ever existed...in the latter part of the fifth century [BC] something like a coherent Aesop legend appears, and Samos seems to be its home."

(Not my personal copy of the book. I don't have one.)

Some additional notes on the second passage above:

1. Seeing as there is considerable uncertainty as to whether "Aesop" refers to an actual person, stating that he was a writer of some kind when neither original writings attributed to him nor specific, creditable references to the existence of such writings in literary, or book, form survive, is obviously taking a bit of a liberty.

2. Most ancient sources appear to agree that the supposed Aesop lived in Samos and was a slave at some point. His place of birth on the other hand was much disputed among these same sources: claims were made more Mesembria in Thrace, the city of Sardis in Lydia (Western Asia Minor), and the country of Phrygia, which was east of Lydia, in present-day west-central Anatolia. None of these places appear to have a stronger claim than any of the others. There does seem to be some consensus, tentatively approved by modern scholarship as at least the most likely dates if there are to any at all, that Aesop would have been born around 620 B.C. and died around 564. More on this in a later note.

3. Plutarch, supposedly in the Life of Solon (I don't remember this), relates the story of Aesop's death in Delphi (more below), in which he states that Aesop was in Delphi on a diplomatic mission from King Croesus in Lydia. This is the primary source of the speculation that Aesop was at one point freed from slavery.

4. I am going to quote from the Wikipedia article re this one: "[Aesop scholar Ben Edwin] Perry...dismissed Aesop's death in Delphi as legendary; but subsequent research has established that a possible diplomatic mission for Croesus and a visit to Periander are consistent with the year of Aesop's death."

There is also a long tradition of speculation that Aesop may have been of black African origin or descent, based on descriptions and depictions of him as swarthy and of otherwise unusual appearance.

So I have never read through one of the serious compilations of Aesop's Fables. Aesop may also be the only ancient Greek content originator on this new list that was not read, and maybe even not talked about, at SJC Annapolis, though it is possible sentences or fragments from him were used as exercises in our Greek manual/textbook Still, now that we have our first ancient Greek on board the site, as well as an Italy-based ancient Roman, it is starting to really feel like the monument to lost ambitions and lost possibilities I have hoped to build up here. We still need to get some of the French in here especially, and the Germans and Russians as well, for the mausoleum of my mind to attain something like its full form, but I am beginning to see it coming into shape.

I am going to include Samos and Delphi, as the places most associated with the life and death of Aesop, on the travel list. They are places one would want to see anyway, and the excuse for giving them the official imprimatur of being on the List and therefore priority destinations, is too convenient.

1947 short film of "The Tortoise and the Hare". The matter of interest to me in this is that the movie is a Encyclopedia Britannica/University of Chicago production. I did not know that they dabbled in filmmaking at this time, and of course this is right during the period when they were cranking up all the Great Books stuff. The film has its charm, though I am surprised at how gratingly Middle American the voice of the narrator was. I was anticipating maybe one of the myriad genius European professors that were on campus at the time, or at least a top-shelf graduate student.

Monday, September 3, 2012

Publius Vergilius Maro

"Virgil has by many scholars been considered the greatest of all poets and the Aeneid was his greatest work...Virgil wrote in the classical Latin of the Golden Age." (IWE)

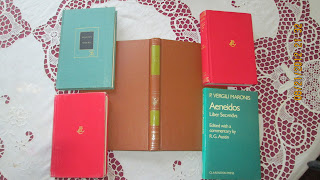

The Aeneid was the only work of the great poet's to be chosen for the 1958 reading list, however. It is also the only one of his that I have read as yet, though I am convinced that there is considerable greatness in the Eclogues and the Georgics, though like the Aeneid, the better part of this greatness is probably lost on anyone who is not very much at home in the Latin language. It is my impression that hardly anyone, at least who has a prominent public presence, knows Latin this intimately anymore, and even most among the super-educated do not seem to consider it a pressing issue. One result of this is that Virgil, one of the pillars of the Western intellectual tradition for two millenia, is rapidly becoming lost to the Culture (in an old post on the other blog relating to this same issue I used the phrase "any communal, non-specialist human consciousness" in place of Culture, to describe what he had been lost to), along with other Roman poets, Horace perhaps most prominent among these. I of course do not know enough Latin to read its literature without a translation myself. At this point I suspect most people hold some variation of the opinion that this kind of reading does not in most cases provide tangible value to a person's development--it is true I think that the amount of immersion and mastery that is necessary with regard to these studies to attain such tangible values as may be found therein is far greater than is generally appreciated even by people who would earnestly be interested in seeking them. Still, we are speaking of the widely acknowledged pinnacle of the literature of the language of the Roman Empire, the central language of Western thought for over a millenium after that empire's demise, one of the five great epic poems, traditionally considered to be the highest of all literary achievements, of Western/European history, a source of episodes and myths that recur throughout art and thought down through the ages. Surely all this would be of interest to some class of serious person...

My collection of Virgil books. The first time I read The Aeneid, which was at the beginning of my sophomore year of college, I used the old Scribner's edition with the Rolfe Humphries translation, which I do not appear to have anymore. I have no idea when I jettisoned it. Maybe I didn't like it, although in my memory I had a fondness for it at the time, and the fairly clear memory I have of the physical book anyway would seem to confirm the truth of this. I also remember my wife, who would also have had to read this stuff, has having a copy of the Robert Fitzgerald translation, but we don't have this anymore either. Perhaps at one point a determination was made that one household only needs so many copies of Virgil, though this is not a usual position for us to take. The Brittanica Great Books set was part of another collection that someone (someone apparently quite wealthy, as I found a pay stub for $34,000 wedged into the pages of the first volume of Gibbon) had set out by the side of a rural road around where we live, and which we took up of course, because for us it is so reminiscent of school. On getting the books home though, we did discover that the Rabelais and Pascal volumes were missing; so the set is not complete. The Modern Library edition I think I bought at a library sale in Pennsylvania--I've had it for a very long time. I collect these, especially the ones from the 30s, 40s and 50s, not obsessively, but if I find a stray one in a box for a dollar, I'll pick it up. The translator of the Great Books edition is Rhoades, and that of the Modern Library is Mackail. I have not read either of these, though my impression from such contact with scholars and translation snobs as I have had is that they are not especially well-regarded.

The two red books obviously are from the Loeb Classical Library. In the summer of 1993, having a lot of idle time on my hands as I did not understand that I should be organizing my plans for after college, I came upon the harebrained scheme of trying to teach myself Latin by working line by line through the Aeneid. As I am very slow to catch on when things are not working, I did keep at it for a fairly long time--I did not finally abandon the effort until around the middle of Book Seven--but neither my knowledge of Latin nor understanding of Virgil progressed very far beyond dim child stage. The green book on the lower right is an Oxford University Press publication intended for the more advanced student. It is the Latin text of Book 2 only, with extensive notes on the grammar, word choices, disparities between manuscripts, comparisons with similar passages in other poets, and the like. I suppose I thought it would be some help to me.

This is a view of the train station in Mantua (Mantova), in Lombardy, taken from the window of a room on one of the upper floors of the ABC Albergo Hotel across the street, on March 2, 1997. Our poet was born in the village of Andes, which no longer exists and has for all intents and purposes long been absorbed into the city of Mantua, which is well established in the popular mind as the hometown of Virgil. At this time I was resident, I suppose it could be said, in Prague and had taken, during the winter break there, a trip to Italy, the prelude and beginning of which I wrote about here. After Venice we moved onto Florence for about four nights, after which it was Saturday, and sometime after lunch we finally made our departure from that city to start back towards Verona, where the bus that had brought us from Prague was awaiting to take us back there Sunday around 3 p.m. I generally like to take my time when visiting places and not try to cram too much in, but I noted that Mantua was only about thirty miles from Verona so as we had walked around the center of Verona on the first day I thought it would be a great idea to spend the last night in Mantua, look around on Sunday morning and zip over on the train in time to catch the bus in the afternoon. This was before one arranged everything on the internet beforehand, or at least before I did, but it seemed easy enough...

The above is supposed to be a likeness of Virgil. The building, which is the Palazzo Broletto, according to my book, or the Palazzo del Podesta, according to the internet, dates from the 1200s, which impresses me, though it is nothing in this part of the world.

We arrived in Mantua sometime in the evening, probably seven or eight. We wandered around for quite a while searching for what was to me an acceptably cheap hotel, but there weren't any, for Mantova is one of the richest cities in the richest region in Italy. Thus we ended up at the hotel across from the train station, which was 95,000 lira, or less than $50 as it was, but that was a veritable fortune to me at the time. There was a freaking telephone in the room! In truth we were running low on funds at this point, but we were able to get a pizza and some cheap wine in a place equal parts pleasant and raucous adjoining the train stations. I love train station restaurants; of course everything--the station, the surrounding district of the town, and the restaurant--has to be old, the way it would have been before 1965, where they frequently serve as settings in movies and novels. Many of the old cities in Italy have happily not had their ancient plans, at least in their central parts, as much improved upon in recent decades as those elsewhere have.

Picture of me back when I was at least thin underneath Virgil's niche, and a slightly expanded view of the palazzo. I am still favoring the shapelessly fitted earth tones that were the fashion among some people in the early 90s. Spring of '97 was about the time all of that really began coming to an end, though those kinds of shifts are way too subtle for me to pick up on in real time. When seeing youthful pictures of myself like this, I am happy that I at least had the opportunity to go to some of these places when I was still young, and I have some good memories of them, but they are always accompanied by the knowledge that I did not begin to make the most of those opportunities in any way. This is off-topic, but I was watching the movie Chariots of Fire recently, and wondering why it had such a powerful effect on people of middling intelligence and accomplishment, myself included, but induced diffidence at best in most people who operate at a world-class level, and it struck me that the appeal of the movie to middlebrows was that it shows people who appear to be maximizing their potential, in various areas of life, at every instance of those lives that is shown on the screen, which is actually quite rare in movies, but are at the same time not doing anything in a way that seems completely inaccessible to bourgeois audience members. Holding one's own with the toffs at Cambridge seems (in this movie anyway) like a skill one could learn if one was exposed to them enough and had the right kind of instruction at the necessary stages of life. Anybody could be as devout a Christian as Eric Liddell--there isn't even competition involved to prevent you from attaining this goal--if it were possible for him to derive satisfaction from that kind of life, which most people will dismiss out of hand. Even winning the Olympics is not such a daunting task when the only people you have to beat are graduates of elite universities from about eight countries, and the likes of Usain Bolt aren't going to be walking through the door. Anyway, in most of the important areas of life--the physical, the intellectual, the sensual, the social, the active useful--I spent most of my formative years watching from the fourth row back on the sideline.

The above is the main square in old Mantua, with the duomo on the left and the palazzo of the doge, or duke, or whatever the person was called that ruled the city back in the Medieval/Renaissance era. As you can see hardly anyone is out, because it is Sunday, and places like Mantua completely close down on Sunday in Italy, as well as much of the rest of Europe. This particular visit, pleasant though it was in many ways, was a reminder that one should always plan on Sunday to be in or on the way to a big city, or at least a fairly popular one. Nothing was open. We had to go back to our pizzeria of the night before but we only had enough cash left (after buying our train tickets) to get a tiny plain pizza and tap water--ATMs in the provinces did not work for foreign bank cards on Sundays at that time either.

Statue of Rigoletto. This house had a connection with Verdi. He used it as a set model for many of his operas. I don't know why, however, which would be a slightly more interesting tidbit to know.

Mantua is an ancient city, and there are blocks of medieval streets and buildings that are not exactly obsessively preserved. There were, as I have noted several times, very few people out on the streets, and the majority of the population that one did see were senior citizens. Even at that time the birthrate in the prosperous areas of northern Italy were historically low--less than 1 child per woman in nearby Bologna, and I doubt it was much more than that in Northern Lombardy and one saw very few children, and these almost always single children accompanied by three or four adults. The preponderance of old people was very noticeable.

This is part of the modern Virgil monument, which was apparently commissioned by Mussolini in 1927, though I was not aware of this at the time, or did not make the connection. I can't make out the verse inscribed on the plinth anymore, but I am going to make a guess that the figures represented here are supposed to be Aeneas and Turnus (or perhaps Mussolini and Georges Clemenceau, whom the Turnus figure somewhat resembles).

I've always wanted to slip this disclaimer in in one of my blog posts, that I am aware I have a terrible whining problem, and always have, and that most people from St John's, and this is one of the qualities I find most admirable in my old schoolmates, are, like my wife, most decidedly not whiners, and are generally competent and achieve above-average success as adults. It is a very fine school for people who understand how to work and have a strong connection to areas of life outside of the college. Our students of this description tend to do very well in the world, and contribute to society in substantial ways. The college even helps its many alumni who are lazy, delusional, emotionally needy and frightened of most aspects of regular American society to lead a far more bearable life than they would likely have been able to manage without it; but it can only do so much.

The whole of the Virgil monument. I did think this commanding depiction of Virgil seemed a little out of sync with his traditional reputation as a lover of the quiet, rural life. This is located in a large park adjacent to the old part of town. It was the last thing we saw before heading back to the train station.

My ingenious plan to make it back to Verona in time for the bus did not proceed entirely smoothly. First of all, even though the two cities are just 30 miles apart, the main train lines that they lie on are separate. There is a branch line that runs between the two cities as a kind of local. However it only runs a couple of times on Sunday. Then of course, Mussolini not being in charge of the country anymore, the trains did not run on time, and as there was no one else waiting in the station, including, at that point, the people in the ticket booth, this girl was not too happy with me, and was dubious that any train was going to Verona that day at all, though the posted schedule in the station indicated that one indeed ought to be arriving imminently.

I wait in the empty station. Needless to say the train did come, and we did make it to Verona on time, though barely--the other passengers were already seated on our bus when we pulled in. The ride between the two cities through the farmland of the Po Valley was ungodly beautiful and evocative of myriad things about Europe and Western Civilization that I had presumed to be over, and that I still presume will be over soon enough, but boy did it take its time getting there. This was not one of those high-speed trains zipping across the Euro-countryside that so much is made of. No, this was decidedly retro.

Behind the Chiesa di Santa Maria di Piedigratta in Naples (near the Mergellina subway station, it looks like) there is a Roman grotto in which one of the monuments is traditionally called Virgil's tomb. It is not, actually, but it has been referred to as such since the 1100s, and it is still maintained with a certain amount of reverence, so I am going to count it. Besides, I don't have a lot of sites in Naples on my list, and I want all the excuses to make it there someday that I can get.

Monday, August 27, 2012

Why Am I Doing This?

This is a pure reversion site, a means to cope with various disappointments and resignations of middle age that can impinge upon one's ability to live contentedly. While it is true that this page's mother site (bourgeoissurrender.blogspot.com) was wrenched into being six years ago for largely these same reasons, and has been on the whole unsuccessful in its purpose, this sideline is much more modest about what it is and can be expected to be, and is intended to be a place where such unburdening as must go on can be indulged in as minimalist and prosaic a manner as can be mustered.

The main disappointment that this site particularly addresses is my failure to become in any meaningful way a lettered person, the attainment of which would also imply cosmopolitanism and acceptable intelligence and a number of other desirable qualities that I actually once took for granted I would be identifiable as possessing regardless of what heights I should have scaled in the field of literature. It seems now that the appeal of this calling to me was emotional and romanticized only; if I had any understanding of the real nature of the skill and intelligence and spirit involved in the production of literature or history or geography, let alone any of the 'hard' areas of learning and achievement, it was a flimsy one. So now, at age forty-two, flummoxed by a lack of development and progression that seems impossible to effectively counteract, I am retreating into the comfort of adolescent nostalgia, for my earliest experiences of books, and especially literature, as a component of one's sensibility or worldview, so I can try to figure out why it struck me that this was to be my life's path; which it still has been, however unobservable the influence is from almost any distance.

I was thirteen or fourteen when my parents brought home, on a whim, a full set of the 1966 edition of the Illustrated World's Encyclopedia that they must have picked up cheaply. The writing level of the body of this reference book was in many respects almost babyish, and of course it was already nearly twenty years out of date, but: I had always wanted a set of encyclopedias, even at the age of thirteen I did not think it a great loss that the advancements of knowledge and history of the two last decades should be missing, there were a number of features in it such as explanations of the rules of various card games which I had not previously realized I had wanted, and the photographs and illustrations seemed to me to depict a more optimistic, happier and educationally exciting world than that with which I was familiar. That it was (probably) a particularly insidious lie did not have any effect on my feelings; I liked and welcomed it. The main attraction of this set of books, located in the rear of every volume, were short blurbs, plot summaries and amusing line drawings of scenes from their selections of the World's Greatest Literature, the books--mostly novels of the most recent one hundred years--that could form the foundation of a decent middle class American education, which the presentation made seem to be something worth having. The genius of this list's conception was in having popular--and either legitimately or plausibly good--American and British literature of the 1900-1950 period, which even at that time held a great appeal for me, as its anchor, though it only accounted for 30-40% of the total books selected. The rest was filled in by a good but not overbearing scattering of Greek and Roman authors, most of Shakespeare, 17th and 18th century classics, the Regency and Victorian novelists, a broad sampling of the classic, and once thought to be possibly classic, French writers, the Russians of course, more German novels than would be common on such a list today, a substantial selection of currently almost unknown Scandinavians, a smattering of Italians and even a few Spaniards. Given the nature of the encyclopedia, many children's classics are cited, though these share their place with Dostoevsky and Hardy and Proust. Of course there are multitudes of worthy books, and many authors, left off, and many dubious and even embarrassing choices that were included, though I have read a few of the more forgotten titles and in certain instances found them good enough that in combination with their evocation of a sliver of the past, and their present obscurity, gave them a highly poignant quality. I am not here going to concern myself with who or what was left off, but my intention is to revisit the effect upon my imagination and relation to the entire world that this rather stupid list had upon me.

So I read from this list rather haphazardly--I cut strips of paper, each bearing the title of one of the 300-400 books, which I kept in a plastic cup on my desk, which I shook up and drew a winning ticket from whenever I needed a new book--for close to ten years, though the most dedicated and prolific years of reading were the first two or three, from ages fourteen to sixteen. I was not a complete fanatic at this time. There were several books--I remember off the top of my head Diana of the Crossways, All the King's Men, and Nana being among them--that I found completely impenetrable and had to abandon to keep my momentum up, and there were many others--pretty much all of them that weren't middlebrow 20th American works probably--that I was able to get through but understood very little of. Still, I found a great deal that I enjoyed and took inspiration from in these efforts. During the later high school years my dedication fell off and there was a two year period from about eighteen to twenty when, despite not even being in school at the time, I read nothing at all, most of my energies at that time being devoted to wandering around anywhere there might be a hope of my encountering any kind of social life (there was none). I did spend a lot of time in libraries in these years but my reading consisted mostly of newspapers and magazines and skimming easily readable books--I evidently could not concentrate on anything very long at this period. Eventually I did make it back to school, and on occasion, in the summer especially, I would dip back into the old list again, and after I finished/graduated I thought I would perhaps continue on with it. But about six months after leaving school, with my life in considerable disarray with regard to finances and employment, having gotten through about one and a half books, completely unable to undertake any writing, and my literary needs with regard to quality and high historical importance having at that time been raised quite a bit as a result of my time in college (this stringency of taste has abated some in recent years as it becomes rarer for anything to affect me intensely), I determined, curiously, that the first thing I had to do to restore some sense of order and purpose and self-respect to my life was to start on a new, and better, reading list. And to a great extent this did work, and although I have never made much advancement in my economic or career status--while I have some sense of how to organize and build a foundation, I have, sadly, little of how to advance from there--I have largely avoided experiencing again the total emptiness and self-hatred I felt when I was on no such regular plan.