A List: Aldous Huxley--Time Must Have a Stop........................................61/311

B List: Ellen Glasgow--Barren Ground....................................................168/526

C List: H. R. Ellis-Davidson--Gods and Myths of Northern Europe........194/251

New books this month. Time Must Have a Stop was published in 1944, but it is set, thus far at least, in the 20s. I don't have a great sense yet of what it is about, but it features clever, eccentric characters of a certain epoch of English history who have enviable literary educations, so I appreciate that. The big drama in the book at the moment concerns a teenage boy who is unsuccessfully lobbying his brilliant but inattentive father to get him some evening clothes. Just before this I read two noteworthy short stories for the "A" list, "The Bulgarian Poetess" by Updike, which at one time at least was one of his more celebrated and most frequently anthologized stories, and "The Life You Save May Be Your Own", by the incomparable Flannery O'Connor. Updike reminds me of Graham Greene in the sense that he turned out a prodigious volume of professional writing over decades that seems as a rule to be worth reading for its own sake and contains its own interest almost independent of its subject matter. The premise of "The Bulgarian Poetess", in which an American writer briefly meets and is enchanted by the poet of the title at a conference behind the Iron Curtain to promote cultural understanding, which causes him to lament that they are not free to become better acquainted, seems rather quaint today, and is growing quainter by the hour, even though this was the world I grew up in until I was 19. Flannery O'Connor is one of the best writers of dialogue I have ever come across. It is artificial in the sense that almost no one ever talks like her characters do, or is capable of doing so, but the thoughts and conversations of those characters strikes one as what conversation, or writing, could attain if their practitioners always knew exactly what they wanted to say and what their purpose was in saying it. This is really one of the core principles of what literature is and why it is actually important, but I at least tend to lose sight of that.

I was looking forward to the Ellis-Davidson book, which is from 1964, a period whose scholarship in and interpretation of the humanities I have tended to trust for most of my life, though as that era grows ever more remote in time I am more able I think to see where their blind spots were at least even if I cannot wholly buy in yet to the more brashly asserted new developments and interpretations, where these exist. The book is in large part a survey in the style of Edith Hamilton, but less entertaining to read, drier, more academic, etc. I tend to doze off after 4 or 5 pages when I am reading it even though it is not uninteresting. I have largely given up trying to read late at night now because I can't stay awake, so this is happening in the afternoon. I don't fall asleep reading everything (yet), and I find that a good literary prose style is still able to engage me and keep me alert. But I suspect any denser philosophers and novelists are going to increasingly be a challenge for me.

I had been feeling healthier and somewhat more cautiously optimistic lately as the new school year started but I am a little off tonight.

Thursday, September 6, 2018

Thursday, August 23, 2018

Charles Dickens--Barnaby Rudge (1841)

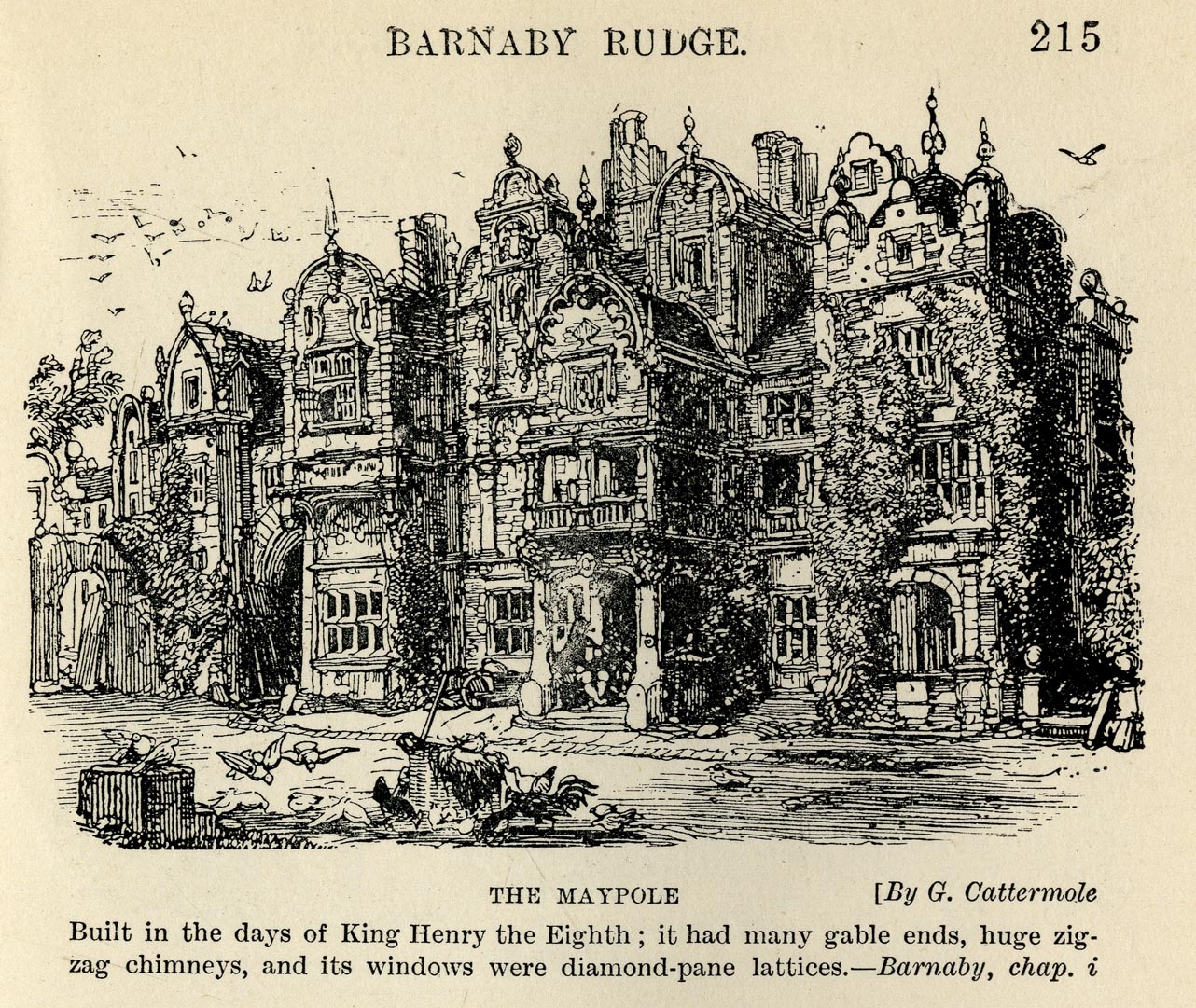

First Dickens on the list, of the nine I think that are on it. This was a good one to start with, as it is one of his celebrated efforts, and I had not read it before either. It is evidently not thought highly of by many readers, especially on the internet, but I liked it, as I tend to do with most Dickens books. I had thought that A Tale of Two Cities was his only book with a historical setting, but this one goes back to an even earlier event, the anti-Catholic riots that took place in London in 1780, which episode of history I must cop to being unfamiliar with. I don't even recall its coming up in the life of Johnson, though maybe it did. It's one of the early books, and the beginning especially I found to be very funny, reminiscent of the Pickwick Papers. The later parts were not as consistently humorous, but the accounts of the riots and their aftermath were compelling and full of interest enough, and while the story is not the smoothest flowing and the characters are not among his most renowned (though I thought John Willett and his cronies, Sir John Chester, Grip the Raven, the Maypole Inn, Mrs. Varden in the earlier parts of the book when she was relentlessly contentious, and even the ridiculous servant Miggs to some extent were skillful creations), the whole was still enviably lively and profuse compared to almost anything else.

The three main complaints about Dickens that I encounter online are that he was paid by the word (which encouraged a general overindulgence in his compositions), that too many plot points are resolved by coincidences, and that his depiction of women is simplistic and generally terrible. I have never found any of these objections to have a marked effect on my ability to enjoy the books, with the possible exception of the last one, as there are times, especially in the earlier books, where even I could wish for the female characters to be a little less insipid and have a more defined character. Barnaby Rudge is not one of his better efforts in this regard, the beautiful romantic interests Dolly Varden and Emma Haredale being little better than mannequins and ciphers, though the Dolly character was apparently very popular with readers at the time. I consider that he improved in this later on--Dora and Agnes in David Copperfield and Esther Summerson in Bleak House have a certain vividness to me years after reading those books. Dora is usually dismissed as being another insipid manic pixie dream girl type, but she was not stupid, only spoiled and overindulged, very much a type one encounters in real life, which cannot be said of most of the young women characters in the earlier books. As to the other criticisms, it appears that the oft-hurled epithet that Dickens was "paid by the word" is not technically true. He was paid to produce a certain amount of copy for the installments of his books, which is what the public in his time was buying, and presumably wanted. As I find his writing and personality amiable for the most part, and am used to the form of the Victorian novel, his alleged wordiness, which is often deployed in the service of some clever or ingenious observation or another, does not put me off. On the matter of his overuse of coincidences, this is a fairly ubiquitous device in literary productions before 1900, and even afterwards, and Dickens seems to me less egregious about it than other older writers, who depend upon it more for their grand effects. Their occurrence in him is usually an afterthought for me.

The Maypole was an inspired invention.

The first 200 pages or so of this were, as noted above, extremely funny. Sadly I neglected to take note of any specific examples for my report, though I suspect a good part of the humorous effect comes from having been set up beforehand in the overall flow of the book, episodes such as Sir John Chester's alighting from his coach after much over the top but entertaining demonstration of his gentility and paying the coachmen "something less than they expected from a fare of such gentle speech."

There is an elaborate and fine description in Chapter LI, too long to reproduce in full here, of the hapless Miggs's desperate efforts to stay awake while accompanying her mistress in sitting up late that is precise, funny, absurd, and mildly uncomfortable in its accuracy. A pointed example of the man's gifts as a writer.

Another one (example) is the depiction of the rioters as viewed from the rooftops in Chapter LXVII.

"...the crowd, gathering and clustering round the house: some of the armed men pressing to the front to break down the doors and windows, some bringing brands from the nearest fire, some with lifted faces following their course upon the roof and pointing them out to their companions: all raging and roaring like the flames they lighted up..." and so on. I think this is very good.

Whether intentionally or not, Dickens comes off as rather pro-establishment here, insofar as he is decidedly anti-rioters, these latter being depicted as a rabble of mostly ne'er-do-wells. The nature of the anti-Catholic sentiment supposed to have inspired the disturbance is easy enough to denounce. History as well as legend being famously written by the victors, rioters can reliably be painted or dismissed as being in the wrong, except when they aren't (the various rebellions of the 1960s come to mind, if most of these are even considered to be riots now). One of the disappointing aspects of this book was the rather unabashed class prejudice in it. The depictions of characters such as Miggs and the pathetic apprentice/would be revolutionary Tappertit are uncharacteristically (to my mind) and needlessly cruel. Meanwhile, the middle class characters who flirt with the movement manage to see where it is heading and distance themselves from it in plenty of time to remain untainted, and the conduct of two Catholic lords whose homes were burnt by the rioters and who refused to accept any of the money offered by the government in compensation were singled out for praise.

Dickens gave the estimated cost of the riots as being from 125,000 to 155,000 pounds, which I guess was a notable sum at that time.

Chapter LXXVII, the execution scene, with its description of the slow progress of the morning sun, the gathering of the crowd, their entertainments while waiting, etc. Also good.

Chapter the Last, of John Willett:

"He left a large sum of money behind him; even more than he was supposed to have been worth, although the neighbors, according to the custom of mankind in calculating the wealth that other people ought to have saved, had estimated his property in good round numbers."

I haven't mentioned the title character, Barnaby Rudge himself at all. He was an "idiot", less attuned to what was going on in the story than his pet raven, and my dislike of mentally limited characters, even when they appear in Dickens, is well documented. Neither he nor his mother brought anything to the story as far as I am concerned.

I have been collecting, and subsequently reading, volumes from the Oxford Illustrated Dickens series since the 90s. While these are new(er) books, they have the essential original illustrations as well as a classic readable typeface. Here is a picture of all my Dickens books from this set that I have acquired so far. On the shelf below you can see that I have the complete set of the Oxford Illustrated Jane Austen as well. Oxford also has put out a similar set of Mark Twain's works, but I don't have any of those as yet.

Here is Barnaby Rudge alone. I struggle with the phone camera to take a clear photo, especially in the surreptitious manner with which I take these photos, as I don't particularly care to be caught on a beautiful sunny day snapping pictures of books.

The Bourgeois Surrender Challenge

1. Scent of a Woman (movie)....................................................1,367

2. Mary E. Pearson--The Kiss of Deception.................................679

3. Bill Bryson--I'm a Stranger Here Myself.................................468

4. Rachel Vincent--My Soul to Lose.............................................192

5. Titans East Part I (Teen Titans: S 03 E 12 TV Show).............150

6. Peter Ackroyd--London: The Biography....................................98

7. Dafydd ab Hugh--Endgame (Doom)..........................................49

8. Victor Hugo--The Man Who Lives.............................................38

9. Annelisa Christensen--The Polish Midwife................................37

10. Ron Roy--The Runaway Racehorse..........................................31

11. Lindsay Hunter--Don't Kiss Me................................................31

12. Harold C. Goddard--The Meaning of Shakespeare, Vol. 1.......24

13. E. N. Joy--Lady of the House....................................................22

14. Work of Robert G. Ingersoll, Vol 1: Lectures............................19

15. Carol Marinelli--The Only Woman to Defy Him.......................14

16. Travis Kennedy--True Ghost Stories and Hauntings................14

1st Round

#16 Kennedy over #1 Scent of a Woman

The ghost story book--not my favorite genre--glides through with a shaky win.

#2 Pearson over #15 Marinelli

Battle of the genre books.

#3 Bryson over #14 Ingersoll

A halfway interesting matchup. Bryson's travel books are the kind of thing that the Challenge was created to give me an excuse to read from time to time.

#4 Vincent over #13 Joy

More genre books

#12 Goddard over #5 Titans

#11 Hunter over #6 Ackroyd

The Ackroyd book I have seen lauded, but he is the victim here of one of my dreaded upsets.

#7 Hugh over #10 Roy

Roy's is a children's book, but I would have given it the victory over an offering from the "Doom" series anyway. However, Hugh has an upset coming.

#9 Christensen over #8 Hugo

The Christensen may be a real book. Anyway she has an upset to pull out too. Victor Hugo's lesser known novels have now turned up several times on the Challenge, usually to be the victim of an early upset. I will have to keep watching for this trend.

Round of 8

#2 Pearson over #16 Kennedy

Because of the library factor.

#3 Bryson over #12 Goddard

The Bryson book appeals more to me at the moment. I haven't read a travel book in a while.

#11 Hunter over #4 Vincent

The library, surprisingly, gives the win to Hunter.

#9 Christensen over #7 Hugh

Final Four

#11 Hunter over #2 Pearson

Hunter is 300 pages shorter

#3 Bryson over #9 Christensen

The libraries don't carry Christensen anyway.

Championship

#3 Bryson over #11 Hunter

An anti-climactic final. However given that I am four or five books behind on the Challenge list, I am happy with the result.

The three main complaints about Dickens that I encounter online are that he was paid by the word (which encouraged a general overindulgence in his compositions), that too many plot points are resolved by coincidences, and that his depiction of women is simplistic and generally terrible. I have never found any of these objections to have a marked effect on my ability to enjoy the books, with the possible exception of the last one, as there are times, especially in the earlier books, where even I could wish for the female characters to be a little less insipid and have a more defined character. Barnaby Rudge is not one of his better efforts in this regard, the beautiful romantic interests Dolly Varden and Emma Haredale being little better than mannequins and ciphers, though the Dolly character was apparently very popular with readers at the time. I consider that he improved in this later on--Dora and Agnes in David Copperfield and Esther Summerson in Bleak House have a certain vividness to me years after reading those books. Dora is usually dismissed as being another insipid manic pixie dream girl type, but she was not stupid, only spoiled and overindulged, very much a type one encounters in real life, which cannot be said of most of the young women characters in the earlier books. As to the other criticisms, it appears that the oft-hurled epithet that Dickens was "paid by the word" is not technically true. He was paid to produce a certain amount of copy for the installments of his books, which is what the public in his time was buying, and presumably wanted. As I find his writing and personality amiable for the most part, and am used to the form of the Victorian novel, his alleged wordiness, which is often deployed in the service of some clever or ingenious observation or another, does not put me off. On the matter of his overuse of coincidences, this is a fairly ubiquitous device in literary productions before 1900, and even afterwards, and Dickens seems to me less egregious about it than other older writers, who depend upon it more for their grand effects. Their occurrence in him is usually an afterthought for me.

The Maypole was an inspired invention.

The first 200 pages or so of this were, as noted above, extremely funny. Sadly I neglected to take note of any specific examples for my report, though I suspect a good part of the humorous effect comes from having been set up beforehand in the overall flow of the book, episodes such as Sir John Chester's alighting from his coach after much over the top but entertaining demonstration of his gentility and paying the coachmen "something less than they expected from a fare of such gentle speech."

There is an elaborate and fine description in Chapter LI, too long to reproduce in full here, of the hapless Miggs's desperate efforts to stay awake while accompanying her mistress in sitting up late that is precise, funny, absurd, and mildly uncomfortable in its accuracy. A pointed example of the man's gifts as a writer.

Another one (example) is the depiction of the rioters as viewed from the rooftops in Chapter LXVII.

"...the crowd, gathering and clustering round the house: some of the armed men pressing to the front to break down the doors and windows, some bringing brands from the nearest fire, some with lifted faces following their course upon the roof and pointing them out to their companions: all raging and roaring like the flames they lighted up..." and so on. I think this is very good.

Whether intentionally or not, Dickens comes off as rather pro-establishment here, insofar as he is decidedly anti-rioters, these latter being depicted as a rabble of mostly ne'er-do-wells. The nature of the anti-Catholic sentiment supposed to have inspired the disturbance is easy enough to denounce. History as well as legend being famously written by the victors, rioters can reliably be painted or dismissed as being in the wrong, except when they aren't (the various rebellions of the 1960s come to mind, if most of these are even considered to be riots now). One of the disappointing aspects of this book was the rather unabashed class prejudice in it. The depictions of characters such as Miggs and the pathetic apprentice/would be revolutionary Tappertit are uncharacteristically (to my mind) and needlessly cruel. Meanwhile, the middle class characters who flirt with the movement manage to see where it is heading and distance themselves from it in plenty of time to remain untainted, and the conduct of two Catholic lords whose homes were burnt by the rioters and who refused to accept any of the money offered by the government in compensation were singled out for praise.

Dickens gave the estimated cost of the riots as being from 125,000 to 155,000 pounds, which I guess was a notable sum at that time.

Chapter LXXVII, the execution scene, with its description of the slow progress of the morning sun, the gathering of the crowd, their entertainments while waiting, etc. Also good.

Chapter the Last, of John Willett:

"He left a large sum of money behind him; even more than he was supposed to have been worth, although the neighbors, according to the custom of mankind in calculating the wealth that other people ought to have saved, had estimated his property in good round numbers."

I haven't mentioned the title character, Barnaby Rudge himself at all. He was an "idiot", less attuned to what was going on in the story than his pet raven, and my dislike of mentally limited characters, even when they appear in Dickens, is well documented. Neither he nor his mother brought anything to the story as far as I am concerned.

I have been collecting, and subsequently reading, volumes from the Oxford Illustrated Dickens series since the 90s. While these are new(er) books, they have the essential original illustrations as well as a classic readable typeface. Here is a picture of all my Dickens books from this set that I have acquired so far. On the shelf below you can see that I have the complete set of the Oxford Illustrated Jane Austen as well. Oxford also has put out a similar set of Mark Twain's works, but I don't have any of those as yet.

Here is Barnaby Rudge alone. I struggle with the phone camera to take a clear photo, especially in the surreptitious manner with which I take these photos, as I don't particularly care to be caught on a beautiful sunny day snapping pictures of books.

The Bourgeois Surrender Challenge

1. Scent of a Woman (movie)....................................................1,367

2. Mary E. Pearson--The Kiss of Deception.................................679

3. Bill Bryson--I'm a Stranger Here Myself.................................468

4. Rachel Vincent--My Soul to Lose.............................................192

5. Titans East Part I (Teen Titans: S 03 E 12 TV Show).............150

6. Peter Ackroyd--London: The Biography....................................98

7. Dafydd ab Hugh--Endgame (Doom)..........................................49

8. Victor Hugo--The Man Who Lives.............................................38

9. Annelisa Christensen--The Polish Midwife................................37

10. Ron Roy--The Runaway Racehorse..........................................31

11. Lindsay Hunter--Don't Kiss Me................................................31

12. Harold C. Goddard--The Meaning of Shakespeare, Vol. 1.......24

13. E. N. Joy--Lady of the House....................................................22

14. Work of Robert G. Ingersoll, Vol 1: Lectures............................19

15. Carol Marinelli--The Only Woman to Defy Him.......................14

16. Travis Kennedy--True Ghost Stories and Hauntings................14

1st Round

#16 Kennedy over #1 Scent of a Woman

The ghost story book--not my favorite genre--glides through with a shaky win.

#2 Pearson over #15 Marinelli

Battle of the genre books.

#3 Bryson over #14 Ingersoll

A halfway interesting matchup. Bryson's travel books are the kind of thing that the Challenge was created to give me an excuse to read from time to time.

#4 Vincent over #13 Joy

More genre books

#12 Goddard over #5 Titans

#11 Hunter over #6 Ackroyd

The Ackroyd book I have seen lauded, but he is the victim here of one of my dreaded upsets.

#7 Hugh over #10 Roy

Roy's is a children's book, but I would have given it the victory over an offering from the "Doom" series anyway. However, Hugh has an upset coming.

#9 Christensen over #8 Hugo

The Christensen may be a real book. Anyway she has an upset to pull out too. Victor Hugo's lesser known novels have now turned up several times on the Challenge, usually to be the victim of an early upset. I will have to keep watching for this trend.

Round of 8

#2 Pearson over #16 Kennedy

Because of the library factor.

#3 Bryson over #12 Goddard

The Bryson book appeals more to me at the moment. I haven't read a travel book in a while.

#11 Hunter over #4 Vincent

The library, surprisingly, gives the win to Hunter.

#9 Christensen over #7 Hugh

Final Four

#11 Hunter over #2 Pearson

Hunter is 300 pages shorter

#3 Bryson over #9 Christensen

The libraries don't carry Christensen anyway.

Championship

#3 Bryson over #11 Hunter

An anti-climactic final. However given that I am four or five books behind on the Challenge list, I am happy with the result.

Monday, August 6, 2018

August 2018

A List: Leo Tolstoy--The Cossacks......................................114/170

B List: Charles Dickens--Barnaby Rudge............................623/634

C List: John Steinbeck--East of Eden..................................500/601

It's been a very busy summer, and not as much time to sit around reading as I might like. However, I will obviously be finished Barnaby Rudge and working on that report soon, and once that happens I can wrap up East of Eden too, a book which I have noted in past monthly reports that I am very fond of.

Tolstoy is always Tolstoy, naturally, though I thought that compared with other things I had read of his that The Cossacks during the beginning stages after the main character leaves Moscow and first settles in the Cossack territory was more like a conventional European novel of the 19th century, albeit a perfectly good one, but not as imbued with the special Tolstoy quality with his other books. However as the story progresses it is taking on more and more of that beautiful shape that comes from seeing and understanding the way people experience life in the most crucial instances of it (and small repetitive habits or instances of noticing can be crucial facets of experience, at least in literature and other art).

It's been a very hectic summer. Some changes are going on my house that have multiple rooms in a state of disarray. The children, while they have some activities, are not excessively busy, but there are just so many of them. It has been very hot as well, it has been in the mid-90s on several occasions, and living in an old house in the north we don't have air conditioning apart from window units in a couple of the bedrooms. No vacation or even very many outings. We've been to the Maine coast only once, on the fourth of July! It's a summer of reorganization.

B List: Charles Dickens--Barnaby Rudge............................623/634

C List: John Steinbeck--East of Eden..................................500/601

It's been a very busy summer, and not as much time to sit around reading as I might like. However, I will obviously be finished Barnaby Rudge and working on that report soon, and once that happens I can wrap up East of Eden too, a book which I have noted in past monthly reports that I am very fond of.

Tolstoy is always Tolstoy, naturally, though I thought that compared with other things I had read of his that The Cossacks during the beginning stages after the main character leaves Moscow and first settles in the Cossack territory was more like a conventional European novel of the 19th century, albeit a perfectly good one, but not as imbued with the special Tolstoy quality with his other books. However as the story progresses it is taking on more and more of that beautiful shape that comes from seeing and understanding the way people experience life in the most crucial instances of it (and small repetitive habits or instances of noticing can be crucial facets of experience, at least in literature and other art).

It's been a very hectic summer. Some changes are going on my house that have multiple rooms in a state of disarray. The children, while they have some activities, are not excessively busy, but there are just so many of them. It has been very hot as well, it has been in the mid-90s on several occasions, and living in an old house in the north we don't have air conditioning apart from window units in a couple of the bedrooms. No vacation or even very many outings. We've been to the Maine coast only once, on the fourth of July! It's a summer of reorganization.

Thursday, August 2, 2018

Greece

1. Attica.............................................................13

According to the accompanying article, these ladies may have booked a trip to Attica (tourism from Germany is evidently booming there).

2. Peloponnese....................................................6

3. Central Greece................................................3

Eastern Greece................................................3

5. Central Macedonia......................................... 2

East Macedonia & Thrace...............................2

Thessaly...........................................................2

West Greece.....................................................2

9. Epirus...............................................................1

Ionian Islands...................................................1

North Aegean...................................................1

South Aegean...................................................1

Tuesday, July 10, 2018

July 2018

A List: Philip Jose Farmer--To Your Scattered Bodies Go.......................193/217

B List: Charles Dickens--Barnaby Rudge.................................................278/634

C List: John Steinbeck--East of Eden.......................................................434/601

To Your Scattered Bodies Go, which I had never heard of, is a science fiction novel, a rarity on the A list, from 1971. As I have often found to be the case with science fiction books, the concept is more interesting to me than the execution. In the beginning of the book dead people from all ages of history, up to around 2008 as far anyone can tell, have been resurrected on some kind of strange planet. Several of the characters are well known personages from history. The main character is the Victorian adventurer Sir Richard Burton, and Alice Liddell and Hermann Goring are among the others who show up. I liked it in the early part of the book when the characters kept picking up bits and pieces of information about historical developments, scientific discoveries, and so on, that occurred after their earthly deaths. However as the book goes on the attachments to their former lives on earth fades and there is sort of endless fighting and constant violent death and resurrection. It is not a cheery vision of the afterlife. Hermann Goring, who keeps dying and getting resurrected in the same places as Burton, is not exactly portrayed sympathetically, and no one really likes him, but he is not someone who is, or can be, completely shunned by the other resurrected people as might be expected by today's mores, and at first he is even able to amass a considerable amount of power among the dead. I assume we are building up to some important climax in what remains of the book.

The story has a number of characteristic late 60s-early 70s touches. Everyone is resurrected naked and hairless in their 25 year old bodies and there is, initially at least, a lot of sex (Burton bags Alice Liddell and Goring gets a six foot tall voluptuous Swede). Nothing resembling modern feminism makes an appearance even as a wild rumor. The women exist to have sex with and fight over, and there isn't a single one who makes a pretension towards leadership in the primitive world of the resurrection. Human civilization appears to have come to some kind of catastrophic end in 2008, since a massive number of people died in that year but in no later one. Pollution and overpopulation are given as two of the causes of the disaster, which is in keeping with popular thought at the time. It was a prescient year to land on for some kind of crisis however.

Philip Jose Farmer was born in 1918 in Terre Haute, Indiana, and died in 2009 in Peoria, Illinois. He graduated from Bradley University in Illinois when he was 32. He looks to have written fifty books or more. Judging by this and the plot outlines of some of his other novels, he inclined towards a dystopian view of life.

Due to its being summer and my not having as much time to read as well as the unusual circumstance of having two 600 page novels by major figures from the past (in my literary upbringing anyway) coming up at the same time, I am on something of a hiatus from East of Eden, with the exception of one day when I left my Dickens book in Vermont. It is not that I don't like it. As I believe I said in last month's entry, I like it much more than I was expecting to, and I find it oddly calming, which is good for me now, because my life at the moment is a little more overwhelming and full of annoying stressors than I would like. I like the way the characters, especially the male characters, talk in Steinbeck. It doesn't resemble the way anyone talks in real life, especially nowadays, but I wish they did. The conversation is deliberate, and focused on matters of substance in a searching, well-disposed way. I suppose it reminds me of what I think of as a good college class, that being about the extent of my experience of halfway intelligent conversation. But anyway, that is wherein the book's charm consists for me. I will go back to it when I finish the Dickens and am writing up the report for that, which will take me at least a week.

B List: Charles Dickens--Barnaby Rudge.................................................278/634

C List: John Steinbeck--East of Eden.......................................................434/601

To Your Scattered Bodies Go, which I had never heard of, is a science fiction novel, a rarity on the A list, from 1971. As I have often found to be the case with science fiction books, the concept is more interesting to me than the execution. In the beginning of the book dead people from all ages of history, up to around 2008 as far anyone can tell, have been resurrected on some kind of strange planet. Several of the characters are well known personages from history. The main character is the Victorian adventurer Sir Richard Burton, and Alice Liddell and Hermann Goring are among the others who show up. I liked it in the early part of the book when the characters kept picking up bits and pieces of information about historical developments, scientific discoveries, and so on, that occurred after their earthly deaths. However as the book goes on the attachments to their former lives on earth fades and there is sort of endless fighting and constant violent death and resurrection. It is not a cheery vision of the afterlife. Hermann Goring, who keeps dying and getting resurrected in the same places as Burton, is not exactly portrayed sympathetically, and no one really likes him, but he is not someone who is, or can be, completely shunned by the other resurrected people as might be expected by today's mores, and at first he is even able to amass a considerable amount of power among the dead. I assume we are building up to some important climax in what remains of the book.

The story has a number of characteristic late 60s-early 70s touches. Everyone is resurrected naked and hairless in their 25 year old bodies and there is, initially at least, a lot of sex (Burton bags Alice Liddell and Goring gets a six foot tall voluptuous Swede). Nothing resembling modern feminism makes an appearance even as a wild rumor. The women exist to have sex with and fight over, and there isn't a single one who makes a pretension towards leadership in the primitive world of the resurrection. Human civilization appears to have come to some kind of catastrophic end in 2008, since a massive number of people died in that year but in no later one. Pollution and overpopulation are given as two of the causes of the disaster, which is in keeping with popular thought at the time. It was a prescient year to land on for some kind of crisis however.

Philip Jose Farmer was born in 1918 in Terre Haute, Indiana, and died in 2009 in Peoria, Illinois. He graduated from Bradley University in Illinois when he was 32. He looks to have written fifty books or more. Judging by this and the plot outlines of some of his other novels, he inclined towards a dystopian view of life.

Due to its being summer and my not having as much time to read as well as the unusual circumstance of having two 600 page novels by major figures from the past (in my literary upbringing anyway) coming up at the same time, I am on something of a hiatus from East of Eden, with the exception of one day when I left my Dickens book in Vermont. It is not that I don't like it. As I believe I said in last month's entry, I like it much more than I was expecting to, and I find it oddly calming, which is good for me now, because my life at the moment is a little more overwhelming and full of annoying stressors than I would like. I like the way the characters, especially the male characters, talk in Steinbeck. It doesn't resemble the way anyone talks in real life, especially nowadays, but I wish they did. The conversation is deliberate, and focused on matters of substance in a searching, well-disposed way. I suppose it reminds me of what I think of as a good college class, that being about the extent of my experience of halfway intelligent conversation. But anyway, that is wherein the book's charm consists for me. I will go back to it when I finish the Dickens and am writing up the report for that, which will take me at least a week.

Thursday, June 14, 2018

Pierre Caron de Beaumarchais--The Barber of Seville (1775)

One more shorter reading--there has been a little series of them here. Long more celebrated in this country at least in its operatic incarnation, surprisingly few English editions of this play have been published in the last century, apart from a Penguin edition that gets reprinted from time to time. The only old hardcover copy of the sort that I like to collect that I could find was a book from the 1893 Heath's Modern Language Series, an American school book that has the play in French, with an introduction and extensive notes in English. As the play runs only 83 pages, the language is mostly classical (and therefore consistent and unconfusing) French, the notes are directed at readers whose reading level in that tongue is not more advanced than my own, and as I often find English translations of pre-revolutionary French plays to be unsatisfying, I decided to read it in the French. On the whole this was successful; reading over the summary in the IWE the only major plot point that escaped me was that Bartholo was persuaded in the end to agree to give up Rosina so easily because it was suggested that as her guardian there might be an investigation into what had become of her property. I am not sure why I missed that, because it is not an obscure or difficult passage. Perhaps I was tired or otherwise distracted by that point (it was on the second to last page) and it failed to sink in.

From the IWE introduction, which I confess I am not sure makes any sense:

"The Barber of Seville is now best known in the history books (?), though it was only a symptom and not a contributing factor in the last mad years of the French kingdom."

It's a jolly and entertaining play, great construction, compares favorably with the better English comedies of the Restoration and 18th century, which I also have derived some enjoyment from in the course of my life. Unlike everything else I have been reading lately, there is nothing in this that I can interpret as being about death. It is concerned neither with the past nor the future, but entirely with present action. Figaro is one of those characters of the European tradition whose existence maintains, or did maintain, a sort of universal present and freedom from most of the bounds and constraints that even afflict literary inventions. It contains a humor that seems to me to take much more after the English manner than what is usual in French writing. Its quality is that of being humorous without being over-serious, which has always been a source of much charm in English literature, though not a quality that I have found much elsewhere.

I only took a few notes on this, lines that I found amusing, though they may not work taken out of context. The translations are my own.

My cute little book.

Act II, scene XIV:

LE COMTE: Elle est votre femme? (Is she your wife?)

BARTHOLO: Et quoi donc? (And what of it?)

LE COMTE: Je vous ai pris pour son bisaieul paternal, maternal, sempiternal; il y a au moins trois generations entre elle et vous. (I took you for her great-grandfather, paternal, maternal, eternal; there are at least three generations between her and you).

Act IV, scene I:

BARTHOLO: ...Il vaut mieux qu'elle pleure de m'avoir, que moi je meure de ne l'avoir pas. (It is better that she cries in having me, than that I die of not having her).

Act IV, scene VII:

LE COMTE: Mon maître Bazile, un rien vous embarrasse, et tout vous etonne. (My master Bazile, nothing embarrasses you, and everything astounds you).

Act IV, scene VIII: (an example of the tone of the play's humor)

BARTHOLO voit le comte baiser la main de Rosine, et Figaro qui embrasse grotesquement don Bazile; il crie en prenant le notaire a la gorge. Rosine avec ces fripons!... (Bartholo sees the count kissing the hand of Rosine, and Figaro, who is grotesquely embracing Don Bazile; he shouts in grabbing the notary by the throat. "Rosine, with these rascals!")

From one of the footnotes: "...the excellence of this comedy resides in the acuteness with which Bartholo sees through the devices of his enemies, who have all the harder a task to outwit them."

I believe this is now the second French language book to appear in this program, after Around the World in Eighty Days. While it is exciting to be finally starting to encounter some of the classics of this great tradition almost five years in, it is somewhat funny to consider that we have still to encounter a book written in French that is actually set in France or features nominally French characters. There is not anything especially Spanish about Figaro or the other characters in the Barber of Seville I suppose, though they do not seem to be intensely French either. They have a kind of all purpose continental Latin-derived quality about them. There have been a number of American books thus far with Parisian settings, The American, Alice B. Toklas, part of Anthony Adverse; so we have not had to do entirely without Paris, at least, though it is of course a different kind of Paris.

The Bourgeois Surrender Challenge

Decent Challenge this time, heavy on opera books and antiquities.

1. Lucy Lethbridge--Servants: A Downstairs History of Britain, etc.......................83

2. Leah Kaminsky--The Waiting Room....................................................................40

3. Louis Sachar--Marvin Redpost #4: Alone in His Teacher's House......................31

4. Gustav Kobbe--The Complete Opera Book..........................................................21

5. Charles Osborne--The Opera Lover's Companion.................................................8

6. Pierre Caron de Beaumarchais--The Marriage of Figaro......................................3

7. Honore de Balzac--About Catherine de Medici, Seraphita and Other Stories.......3

8. Benjamin Disraeli--The Young Duke......................................................................1

9. Thomas Hood--Poetical Works of...........................................................................1

10. Rosina Bulwer-Lytton--Cheveley..........................................................................0

11. John Cordy Jeaffreson--The Real Shelley..............................................................0

12. Mabel Wagnalls--Stars of the Opera.....................................................................0

Qualifying Round

#5 Osborne over #12 Wagnalls

Availability

#6 Beaumarchais over #11 Jeaffreson

#7 Balzac over #10 Bulwer-Lytton

#9 Hood over #8 Disraeli

Very close contest. The New Hampshire State Library has both of these books, but the Disraeli is too old to circulate. Also I have read a Disraeli novel before (Vivien Grey) and it did not instill in me any great desire to go deeper in his oeuvre.

Quarterfinals

#1 Lethbridge over #9 Hood

#7 Balzac over #2 Kaminsky

I actually thought Kaminsky might take this one, but her book has not broken through to the libraries (and maybe never will).

#3 Sachar over #6 Beaumarchais

One of those pesky tournament upsets, and over Beaumarchais, who is essentially the host. We have Sachar's famous young adolescent book Holes in our house, and my impression is that at least one of my children has actually read it, so I am not disinclined to see him advance.

#4 Kobbe over #5 Osborne

Epic battle of Opera guides.

Semifinals

#1 Lethbridge over #7 Balzac

The power of the seed and the upset are too great for even the awesome Balzac to overcome here. I'm sure we'll see Honore in the tournament again.

#3 Sachar over #4 Kobbe

Championship

#1 Lethbridge over #3 Sachar

In the end, I want to stick with an adult book on a somewhat different topic than what I have been taking up lately.

Wednesday, June 6, 2018

June 2018

A List: Edith Wharton--The House of Mirth........................................256/347

B List: Between books

C List: John Steinbeck--East of Eden...................................................215/601

While Edith Wharton is a capable enough writer, she is also very much after the manner of Henry James, albeit without some of the density, and I find that going deeper into her oeuvre, at least at this stage of my life, is bringing diminishing returns with regard to pleasure. This book is in much the same vein as The Custom of the Country, and both of these share an obvious bloodline with The Age of Innocence, which I remember writing some complimentary things about at the time I read it. This one is probably not bad for what it is, I just am not finding it to be interesting at this time.

Now East of Eden, on the contrary, I am enjoying a great deal. Remarkably, I had never read any Steinbeck before, even Of Mice and Men, which is still widely read in the schools. This is the kind of book that I was raised on, so to speak, in my earliest forays into literature as a teenager, and it is comfortable to me as far as pace, length, character development and so forth. Whenever I take it up (so far) I never fail to find it interesting, nor do I find myself falling asleep or my concentration drifting when I try to read some in the evening, which is an increasingly important consideration. So it is always exciting to have a book like that going, especially when it has some claim to being a classic, even a minor one or one with a lot of contingencies attached to it. I hope it keeps up.

It's hard to believe that a little more than a hundred years ago central California was barely inhabited. I have never been to California. I still imagine I will make it out there someday, but the years keep going by and there is no real opportunity to take that trip in sight anywhere on the horizon.

One more week and I will have gotten to the end of what has been a very long and particularly grueling school year, after which I'll have 2 1/2 months to try to recover and get ready to survive the next one. Only two more years until people start going to college. Having done essentially no planning for this, as was the case with myself as a youth, though in a somewhat different time when getting through a regular college experience was still reasonably manageable for a middle class person with by traditional standards adequate academic credentials, I can only imagine what that is going to be like.

A lot of pretty girl pictures this month. We should try to include some more serious, or at least artistic pictures too.

The character played by James Dean in the movie is still an infant at the part I am at in the book, which I think bodes well for my continued interest in the story.

America.

B List: Between books

C List: John Steinbeck--East of Eden...................................................215/601

While Edith Wharton is a capable enough writer, she is also very much after the manner of Henry James, albeit without some of the density, and I find that going deeper into her oeuvre, at least at this stage of my life, is bringing diminishing returns with regard to pleasure. This book is in much the same vein as The Custom of the Country, and both of these share an obvious bloodline with The Age of Innocence, which I remember writing some complimentary things about at the time I read it. This one is probably not bad for what it is, I just am not finding it to be interesting at this time.

Now East of Eden, on the contrary, I am enjoying a great deal. Remarkably, I had never read any Steinbeck before, even Of Mice and Men, which is still widely read in the schools. This is the kind of book that I was raised on, so to speak, in my earliest forays into literature as a teenager, and it is comfortable to me as far as pace, length, character development and so forth. Whenever I take it up (so far) I never fail to find it interesting, nor do I find myself falling asleep or my concentration drifting when I try to read some in the evening, which is an increasingly important consideration. So it is always exciting to have a book like that going, especially when it has some claim to being a classic, even a minor one or one with a lot of contingencies attached to it. I hope it keeps up.

It's hard to believe that a little more than a hundred years ago central California was barely inhabited. I have never been to California. I still imagine I will make it out there someday, but the years keep going by and there is no real opportunity to take that trip in sight anywhere on the horizon.

One more week and I will have gotten to the end of what has been a very long and particularly grueling school year, after which I'll have 2 1/2 months to try to recover and get ready to survive the next one. Only two more years until people start going to college. Having done essentially no planning for this, as was the case with myself as a youth, though in a somewhat different time when getting through a regular college experience was still reasonably manageable for a middle class person with by traditional standards adequate academic credentials, I can only imagine what that is going to be like.

A lot of pretty girl pictures this month. We should try to include some more serious, or at least artistic pictures too.

The character played by James Dean in the movie is still an infant at the part I am at in the book, which I think bodes well for my continued interest in the story.

America.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)