In my haste to publish my last article, I forgot that I had wanted to mention some things about the Pulitzer Prize, which was awarded in 1920 to The Age of Innocence. As with other artistic awards, the Pulitzer Prize in the non-journalism categories has almost always been played down by the better writers themselves, and, taking the cue from them, in our days this damping of enthusiasm has spread to much of the reading public. In prestige it is my sense that it has been surpassed by the National Book Award, which looks over time to have a better track record, at least for picking things that later critics and writers have favored; still, the advantage is slight, and it is not something that serious people allow themselves to get overexcited about. The Pulitzer still carried some middlebrow cache in the 60s however--my encyclopedia list duly notes when one of its selections was thus honored, and they did choose 13 fiction winners and 9 drama winners from the 1920-1955 era for inclusion. In 1920 the fiction prize was being given for just the 3rd time, but evidently it was a big enough deal that many of the big writers of the time were aware of it and considered it worth noticing--Pulitzer himself of course had been a titan in the business of the printed word, which meant nothing to purer literary spirits like Ezra Pound, but any kind of prize bearing his name would likely have piqued a certain amount of interest in anyone who wrote at least in part with an eye towards getting or maintaining an upper middle class income.

The point of all this being that according to the chronology of Edith Wharton's life given in the Library of America, the Pulitzer committee actually chose Sinclair Lewis's Main Street (which also appears on this reading list later on--1920 was an exciting year for books in America) as the winner, but the trustees of Columbia University, to which Pulitzer had left the money for and administration of the prizes (and which still administers them, by the way), rejected that selection as too controversial and awarded the prize to Wharton, who, it is said, was appalled by this cowardice and began a correspondence with Lewis which continued for many years afterwards. Wharton was evidently not so appalled that she refused the prize, as Lewis himself would do in 1925 after winning for Arrowsmith (he appears to be the only one who has done so however, for fiction anyway; I had thought it was a more regular occurrence. On the other hand there have been three posthumous winners). Perhaps she was not aware she could do so.

All this information is really nothing to the point, but I had wanted to mention it. It tells us nothing about the meaning of the book. I usually know nothing about the meanings of books, though in this particular instance I think I have slightly more of a grasp on it than usual, because its main themes resemble impulses and feelings that most people living in any kind of conventionally structured society will have. But I would have trouble disconnecting what I think is going on in the book from my personal feelings and experience, and I don't want to go into that on a blog at this time.

Tuesday, June 17, 2014

Monday, June 16, 2014

Edith Wharton--The Age of Innocence (1920)

Despite the constant high level of renown and critical acclaim that has attended this book in both the high and middling levels of literary society almost since the day it came out, and even though I purchased my own edition of it (Modern Library, ed 1950, green cloth cover with black title box) in 1986, I had never gotten around to reading it until now. While I had never dreaded its coming up eventually, I had never gazed upon it with any very lustful anticipation either. My expectation was that it was going to be like weaker Henry James, perhaps slightly less dense, but similarly dry, with the action driven by arch insinuations and subtle cuts that require a great deal of sophistication on the part of the reader to feel the full force of. Also I had read Ethan Frome a few years back for my "A" reading list, and while that book had enough, with its repressive New England setting, to engage my interest and not put me off of Edith Wharton altogether, it was grim enough that I was not running to the library even in my imagination to get at the rest of her ouevre. But while The Age of Innocence is a little like Henry James, and somewhat less like the repressed rural New Englanders of Ethan Frome, I had no trouble staying awake for my nightly fifteen to twenty pages as I have been having with some other recent books on the list, and I even found much of it to be entertaining, though I was not wholly sold on the intensity of the supposed passion between the Countess Olenska and the decidedly room temperature-blooded Archer, especially on her end. That said, my nightly readings of this book provided me the satisfactions and consolations of nostalgia, and the charms of the better parts of the old literature and the old world, bad as we all know that these things for the most part were, that I was looking for when I began to follow this "B" list.

My favorite thing about this book are the descriptions of 'Old New York'. Not so much the society of the best ancient Anglo-Dutch families, though even that was more tolerable than I thought it was going to be, but the geography and topographical references to streets, districts, parks, brownstones, etc, with which we are all familiar, in the particular ways in which they are described here. Even given the extreme wealth of the milieu here, I think the depiction of the scenes and rooms here as I imagine them in reading is more romanticized and more modern than probably even Edith Wharton could have visualized. The majority of the book is set in 1875, with at the end a brief denoument thirty years forward, when the city was considerably more crowded, ethnically diverse, technological, etc, than it had been in the earlier year, and the old elite were having to adapt to the new circumstances, though adapt in this case seems to mean acknowledging their existence, as Archer and his circle continue to hold political and cultural influence, such as serving on the board of the Metropolitan Museum, in 1905, though the forms in which they carried out these offices were somewhat altered. Anyway, as I read the book I imagine the city as an old Hollywood set would have depicted 1870s-1890s New York (or London or Paris of the same period), floodlit, clean, and less incidentally occupied by people or refuse of any kind than it possibly could have been. I think of those houses and streets and squares that have proven, on the whole, so elusive to me to spend any time in at all, and how wide open and easy it always seems to penetrate and live one's whole life in in books. And the same goes of course for London and Paris too.

The Challenge

A very good challenge this time:

1. In Cold Blood--Truman Capote.................................................954

2. A Hero of Our Time--Mikhail Lermontov...................................91

3. Last Night at the Viper Room: River Phoenix and the Hollywood

He Left Behind--Gavin Edwards..................................................68

4. Quidditch Through the Ages--Kennilworthy Whisp....................40

5. Stanford Wong Fails Big Time--Lisa Yee....................................24

6. Under These Restless Skies--Lissa Bryan....................................10

7. Iola Leroy: or, Shadows Uplifted--Frances Ellen Watkins...........6

8. The Voice of the People--Ellen Glasgow.......................................2

9. No Laughing Matter--Angus Wilson.............................................1

Those titles getting the goose egg include The Problem of Cultural Transformation and Individual Integrity in Edith Wharton's Novels by Ihsan Durdu, The War by Christabel Pinkhurst, The Ancient Law by Ellen Glasgow, Female Warriors Volume 1 by Ellen Clayton, & Henrietta Temple by Benjamin Disraeli.

When that quidditch book turned up on the list I figured it was impossible it would not win, so I was pleasantly surprised there. I've always been interested in reading Lermontov, several of Ellen Glasgow's novels (though neither of the two listed here) are actually on this B-list, and I am sure I would like the Angus Wilson book, which "chronicles the end of the bourgeois way of life as seen through the lives of the six M-- children and their dysfunctional middle class family". Wilson was born in Bexhill-on Sea in Sussex in 1913, went to Winchester College and Merton College Oxford, worked as a librarian at the British Museum and as a code-breaker during World War II, wrote satirical novels with a liberal humanistic outlook, and seems to be quite well known in England. I can't believe only one reader has reviewed his book.

However, as the Capote book was the big winner, and as it is famous, and I had never read it, and as Capote, though I have never read anything by him, seems like he would be a kind of writer that I would like, I thought I would give it a look. I was apprehensive about the fact that it was about a real murder and trial and execution, and not only this, but that I thought it was nearly 1,000 pages on the subject. I evidently had gotten it confused with Norman Mailer's book on a similar theme (real-life murderers) which actually is over 1,000 pages. In Cold Blood however is only 343 pages, and my library had it in the hardcover Modern Library edition, with its handsome size and typeface, and I was sold on giving it a go. So far I am on around page 58 and I like it. Of course the graphic stuff has not happened yet. It's been mostly background, the prosperous farmer and his family in 1950s Kansas, with a little bit on the criminals. But the style and tone remind me of the books I liked when I was an adolescent. So the challenge does work sometimes.

Our findings this time produced a pretty good movie challenge as well. Truman Capote swept both events in this competition, pulling off the impressive feat of defeating the movie version of the host book in that contest:

1. Capote...............................612

2. The Age of Innocence........239

3. Baby Face.............................0

I ended up putting all three of these movies in my queue. Even though no one on Amazon has deigned to review Baby Face, it's quite famous among those in the know, a pre-code Barbara Stanwyck picture from 1933. True film connoisseurs love Barbara Stanwyck--I have seen several claim that she is the greatest movie actress of all time--and they also love the (extremely short-lived) pre-code era, which particular designation seems to be restricted to certain daring early talkies from about 1930-33. I have not ventured much into this period, nor into the work of Barbara Stanwyck, other than Double Indemnity, which is a great movie, though I have never have the sense that Barbara Stanwyck's fans consider it an especially great Barbara Stanwyck movie, perhaps because it is fairly well known among the mediocre general public. But anyway, I am going to, hopefully, begin to become initiated in this knowledge and whatever value it possesses.

Wednesday, June 11, 2014

New York (State)

1. New York..................24

2. Westchester...............12

3. Bronx..........................7

4. Suffolk........................6

5. Queens........................5

6. Rockland.....................4

7. Erie..............................3

Otsego.........................3

9. Chemung....................2

Columbia....................2

Essex...........................2

Kings...........................2

Onondoga...................2

14. Albany.......................1

Allegany......................1

Dutchess......................1

Greene.........................1

Madison.......................1

Montgomery...……….1

Nassau.........................1

Rensselaer...................1

Richmond....................1

Saratoga.......................1

Ulster...........................1

Warren.........................1

Washington..................1

2. Westchester...............12

3. Bronx..........................7

4. Suffolk........................6

5. Queens........................5

6. Rockland.....................4

7. Erie..............................3

Otsego.........................3

9. Chemung....................2

Columbia....................2

Essex...........................2

Kings...........................2

Onondoga...................2

14. Albany.......................1

Allegany......................1

Dutchess......................1

Greene.........................1

Madison.......................1

Montgomery...……….1

Nassau.........................1

Rensselaer...................1

Richmond....................1

Saratoga.......................1

Ulster...........................1

Warren.........................1

Washington..................1

Paris

1. 20th Arrondissement..11.5

2. 1st...……………........11

3. 5th.............................7

4. 4th.............................5

5. 6th.............................4

8th.............................4

14th...........................4

18th...........................4

Unknown..................4

10. 2nd..........................3

9th.............................3

16th...........................3

13. 7th...........................2

14. 3rd...........................1

10th...........................1

15th...........................1

17th...........................1

18. 11th.........................0.5

2. 1st...……………........11

3. 5th.............................7

4. 4th.............................5

5. 6th.............................4

8th.............................4

14th...........................4

18th...........................4

Unknown..................4

10. 2nd..........................3

9th.............................3

16th...........................3

13. 7th...........................2

14. 3rd...........................1

10th...........................1

15th...........................1

17th...........................1

18. 11th.........................0.5

Tuesday, June 3, 2014

Ile-de-France

1. Paris (Ile)......................70

2. Val d'Oise..........................4

Yvelines.............................4

4. Essonne...........................3

5. Seine et Marne................2

6. Hauts-de-Seine................1

2. Val d'Oise..........................4

Yvelines.............................4

4. Essonne...........................3

5. Seine et Marne................2

6. Hauts-de-Seine................1

7. Neuilly-Sur-Seine...….....1

Tuesday, April 15, 2014

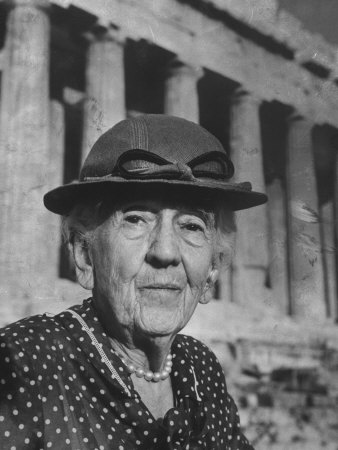

Brief Notes on Edith Hamilton's Mythology (1942)

A fine book, from which I derived much pleasure in the reading and looked forward to each daily section. It seems to be considered as an introductory book on the subject for high school students, something I ought to be beyond by this point of my life. However, while most of the figures and stories are familiar to me, I have still failed to commit some of the more important ones to memory, nor have I ever organized the material in my head as neatly as it is done here. I certainly don't think that I would have gotten very much out of this book as a teenager, without any meaningful prior exposure to classical literature. I also appreciated the simple presentations at the beginning of each section regarding the literary sources from which the myths have come down to us. I am weak on Euripides and have never read Ovid, who were major sources, and I was unfamiliar with Appollodorus as well, whom Edith Hamilton disparaged as a dull and inferior writer, though on numerous occasions she opted to base her account of a story on his versions rather than Ovid's, on the basis of their probably being more truthful to the way it was traditionally told.

The book is written in what I kind of think of as the 'conversational learned style' which lasted from the 20s really up to the early 50s. It is a style to which I have always been partial. The tone is not confrontational nor hyperbolic in promoting the breakthrough in human understanding that the author's researches and insights represent, and humorous observations are dropped in (gently) from time to time at some particularly ludicrous or otherwise illogical aspect of a myth. It organizes and conveys information of a high general interest in a concise, understandable way such as it is not usually presented, and that is also pleasant. Our author assumes a mainly northern European-descended audience for her work: in a brief section at the end on the Norse myths, she writes, as a reason for including these in her survey: "By race we are connected with the Norse; our culture goes back to the Greeks." This sense of the homogeneity of the audience probably accounts somewhat for the intimate tone of the book. In the very short forward when she referred to Shakespeare I thought I detected some affectation or self-puffery with regard to her understanding of the greatness of this author and the serious level she occupied in that game; but perhaps I am overly sensitive to any emphasis people make concerning any superiority they possess. I did not find anything off-putting in her writing about the ancients.

Looking at some of the online reviews, someone wrote that they had taken a mythology class in college and the first thing the professor said was "I hope you all haven't been reading junk like Edith Hamilton". This sort of thing is always very obnoxious because it is unnecessary, even in the unlikely event that someone teaching an undergraduate mythology course is really that far advanced compared to Edith Hamilton both in his understanding and his pedagogy. If the students really learn what you are teaching them, they will presumably come to a similar understanding to that of the teacher, and if they are too stupid to do this, mocking such learning as they do have probably is no help to them. I know there is the problem that ignorant people who have read Edith Hamilton in high school think they know something and that they need to be knocked down a peg and the professor needs to establish that when you are in his class you are playing with the big boys and are dealing with a level of intellectual firepower that, especially if you are from a middle class background, you have probably never encountered before, but I don't think it is helpful in most instances to the students. I also believe that any professor doing this nowadays is probably a complete poser. When I was a student you still had some old Europeans to deal with who may well have spoken five languages by the age of thirteen and heard no other music than what was of the highest quality before they were thirty, but any baby boomer, let alone someone of my generation, who grew up in this country and tries to act like they were born with a deeper understanding of literature and mythology than Edith Hamilton attained in the whole of her earnest life is almost certainly full of it.

The book is written in what I kind of think of as the 'conversational learned style' which lasted from the 20s really up to the early 50s. It is a style to which I have always been partial. The tone is not confrontational nor hyperbolic in promoting the breakthrough in human understanding that the author's researches and insights represent, and humorous observations are dropped in (gently) from time to time at some particularly ludicrous or otherwise illogical aspect of a myth. It organizes and conveys information of a high general interest in a concise, understandable way such as it is not usually presented, and that is also pleasant. Our author assumes a mainly northern European-descended audience for her work: in a brief section at the end on the Norse myths, she writes, as a reason for including these in her survey: "By race we are connected with the Norse; our culture goes back to the Greeks." This sense of the homogeneity of the audience probably accounts somewhat for the intimate tone of the book. In the very short forward when she referred to Shakespeare I thought I detected some affectation or self-puffery with regard to her understanding of the greatness of this author and the serious level she occupied in that game; but perhaps I am overly sensitive to any emphasis people make concerning any superiority they possess. I did not find anything off-putting in her writing about the ancients.

Looking at some of the online reviews, someone wrote that they had taken a mythology class in college and the first thing the professor said was "I hope you all haven't been reading junk like Edith Hamilton". This sort of thing is always very obnoxious because it is unnecessary, even in the unlikely event that someone teaching an undergraduate mythology course is really that far advanced compared to Edith Hamilton both in his understanding and his pedagogy. If the students really learn what you are teaching them, they will presumably come to a similar understanding to that of the teacher, and if they are too stupid to do this, mocking such learning as they do have probably is no help to them. I know there is the problem that ignorant people who have read Edith Hamilton in high school think they know something and that they need to be knocked down a peg and the professor needs to establish that when you are in his class you are playing with the big boys and are dealing with a level of intellectual firepower that, especially if you are from a middle class background, you have probably never encountered before, but I don't think it is helpful in most instances to the students. I also believe that any professor doing this nowadays is probably a complete poser. When I was a student you still had some old Europeans to deal with who may well have spoken five languages by the age of thirteen and heard no other music than what was of the highest quality before they were thirty, but any baby boomer, let alone someone of my generation, who grew up in this country and tries to act like they were born with a deeper understanding of literature and mythology than Edith Hamilton attained in the whole of her earnest life is almost certainly full of it.

Friday, March 14, 2014

Virgil--Aeneid (29-19 B.C.)

Virgil--Aeneid (29-19 B.C.)

This was my fourth time reading the Aeneid (in English, obvs). I have used a different translation each time. Back in school I read the Rolfe Humphries, the Robert Fitzgerald a couple of years afterwards, the Fairclough (Loeb edition), and on this last occasion, the J.W. Mackail (Modern Library). These last two are prose translations. I own the Britannica Great Books edition of the poem, which has a verse translation by James Rhoades. Maybe I will find a reason to take that up in another ten years. There is also a Dryden translation which emits something of a classic aura, however accurate or poetically good it happens to be. The Robert Fagles seems to be considered the best of the modern efforts, and as in the art of translation consensus seems to be that there has been a steady progression over the centuries that continues into our own time, that would make it de facto the best in existence. As with most artistic or intellectual productions I have a hard time warming up to anything too contemporary, that might be alive in some way that has eluded me and therefore will be threatening to my self-esteem, I find I am not overeager to read it. I always even found Fitzgerald's translations, of Homer as well as Virgil, to be too informed by something I vaguely define as modern academic triumphalism, and he goes all the way back to the 60s. At the same time the prose translations, however old they are, are not wholly satisfying either. My favorite is still Rolfe Humphries's, originally published in 1951 and part of the Scribner Library. I know that the associations from the time that I read it, as well as the freshness of reading classic literature and the crazy but aesthetic attractive hopes that the undertaking represented, is coloring my memory, but after all it is precisely this sort of coloring in the midst of (in my instance blushingly tepid) youthful excitement that informs who most of are. That said, Humphries had something of that spare but forceful mid-century style that seems to suit the style and spirit of this poem--or at least what I want the style and spirit of this poem, and most classic literature--to be. Unfortunately I lost my copy of it some years ago or I would give a sample passage.

(According to Wikipedia, Rolfe Humphries was born in Philadelphia in 1894 and died in California in 1969. He was a graduate of Amherst College. Though he was a poet and published in Harper's and the New Yorker in addition to doing his Aeneid translation, he taught Latin in secondary schools until 1957. It is not uncommon in books published before 1960 to find authors or contributors whose titles are "English Department Chairman, Central High School" or the like (though I suspect Humphries probably taught at more exclusive private schools). W. H. Auden called his Aeneid 'a service for which no public award could be too great".

As with Faulkner and,, I am beginning to sense, many of the Great Books, The Aeneid is more or less impossible to read when you are tired or at all distracted. This is a big problem for me, since I rarely have the opportunity to read when I am not tired, and never when I am not distracted. At night, which is when I do, or was planning to do, most of the reading for this program, I usually could not get through more than two pages before my head would begin lolling, I would completely forget where I was, sentences begun would get lost in the mush of my brain and run on into completely nonsensical strings of words, and the book would fall out of my hands (Such is the sad fate to which the failed scholar comes in the end; but I digress). So it took me much longer to read the poem than would seem reasonable. I was averaging 5-7 pages (or about a third of one Book of poetry) a day. When I could stay awake and concentrate long enough to build some momentum and become immersed in the act of reading the book, I felt some of the old enjoyment and happy associations that come even with reading accounts of ancient bloodbaths; thoughts of Italy and the Mediterranean World, of the saga of Western Civilization, now in our own lifetimes apparently dying, in its handsome boyhood, of the destinies of great nations and men, images of my own youth, of clouds slowly drifting across the blue sky of a sunny day when one had all the time and possibility in the world. Of course the primary content of the book if one pays any attention to it, especially in a prose translation, is war and death, in the service of a glorious cause, or several of them perhaps, but nonetheless life and dignity, where the ordinary individual is concerned, is less than cheap. In youth one always identifies with the writer, and the triumph of his vision and art and the strongest of the creations he has employed in the service of this. Greatness and achievement, we think, are often by necessity messy, but no man worthy of the name would suffer to endure life as a mediocre or inferior person anyway. In middle age however, especially in the state of semi-delirium that is the attempt to read late at night, such passages read like this:

"...Next the great meritocrat levelled his spear full on (Bourgeois Surrender) from far...(Surrender), clasping his knees, speaks thus beseechingly...'I entreat thee, save this life for a child and a parent...The victory of Big Money Enterprises does not turn on this, nor will a single life make so great a difference.' (Surrender) ended...The Global Champion grasps his helmet with his left hand, and bending back his neck, drives his sword up to the hilt in the suppliant..."

or

"...(Surrender), slipping down from the chariot, pitiably outstretched helpless hands: 'Ah, by the parents who gave thee birth, great Investor, spare this life and pity my prayer.' More he was pleading, but the Investor, who was also a cardiac surgeon, an attorney, a best selling author and a former Olympic medalist: 'Not such were the words thou wert uttering (before I was present) Die...' With that his sword's point pierces the breast where the life lies hid."

I had wanted to finish the book before my vacation in Florida in order to have something a little less stodgy (and more practical with children) to read on the beach. My slow pace prevented this from being realized however, as I could only get to the middle of Book Ten by the time of my arrival. This actually would not be a bad beach read if one were left unmolested even for a couple of hours a day. I think I only managed to get through about fourteen pages in a week as it was however, and I did not finally finish the book until I got back to New Hampshire.

I have not talked much about he actual book. It is emotional for me, as all of the undisputed canonical books and authors are, because I felt at point in my life to have some connection to this strain of life, that it was in reach for me. It wasn't, so there is a lot of sadness and feelings of pointlessness as trying to revisit them now, but at the same time it evokes images and thoughts from, if not a happier, at least a period of life when one felt the possibility of someday being alive and playing a serious role somewhere in the world.

The Bourgeois Surrender Challenge

The winner of the last challenge, Kobo Abe's Woman in the Dunes, I am reading now, and am about 2/3rds of the way through. I was hoping to read this at the beach if I had finished Virgil, but seeing as the book is a Kafka/Beckettesque story about a man who is unwittingly entrapped in a hole surrounded by fifty foot sand cliffs from which it is impossible to escape, maybe I am glad I did not. It is supposed to be one of the premier Japanese novels of the 20th century, according to my early 90s era Vintage Press paperback copy (they're on the level, right?) Perhaps the translation is inadequate--I remember reading some complaint recently that English translations of Japanese literature were notably weak--but I find the book to be rather thin. Maybe it has one of those remarkable endings that pulls all the seemingly minor incidents and specified objects of the book together. I suppose there is a sense of fineness and of seemingly small things being more significant than or the essential part of bigger things that I think of as characteristically Japanese. But at the moment, on page 156 of 241, I want more of something, not action necessarily, but personality, or demonstration of brain power. Maybe it is too subtle for me and everything I say I want is there, if you can find it (though if this is the case it is really subtle).

On page 136 Abe did get around to writing about sex. This part I think I am clear on:

"Food exists only in an abstract sense for anybody dying of hunger; there isn't any such thing as the taste of Kobe beef or Hiroshima oysters. But once one's body is full, then one begins to discern differences in taste and textures..."

This part lost me though, I have to admit:

"...sex couldn't be discussed in general; it depended on time and place...sometimes you needed a dose of vitamins...sometimes a bowl of eels and rice. It was a well thought out theory, but regrettably not a single girl friend had offered herself to him in support of it, with a readiness to experience sexual desire in general or even in particular. That was natural. No man or woman is wooed by theory alone. He knew this, but he naively observed the theory of the Mobius circle and kept repeatedly pushing the doorbell of an empty house, only because he did not want to commit spiritual rape."

The book is worth finishing, and I am curious to see where it is going after all. I would like to see the movie of it too. I can see where that might be interesting.

The Bourgeois Surrender Challenge

Many of the magic words used in this challenge were too blatantly Aeneid words, so our searches turned up an inordinate number of books with a classical theme about them somewhere. There were also an impressive number of titles by very celebrated authors (Oliver Wendell Holmes, E. B. Browning,Chesterton, Hazliit) with zero or one ranking.

1. Mythology--Edith Hamilton.............................................................267

2. A Grave Talent--Laurie R. King........................................................69

3. The Rise of Rome--Anthony Everitt....................................................59

4. The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes--Conan-Doyle...........................46

5. Age of Bronze (The Story of the Trojan War) Betrayal--Shanower...10

Deadlock--James Reasoner................................................................10

7. Makers of Ancient Strategy--Victor Davis Hanson (ed.).....................9

8. Canadian Adventures of Sherlock Holmes--Stephen Gaspar...............6

McGuffey's Primary Eclectic Primer...................................................6

10. Cassell's Dictionary of Classical Mythology--Jenny March..............5

Encyclopedia of Greco-Roman Mythology--Mike Dixon-Kennedy...5

12. Greek and Roman Mythology A to Z--Kathleen N. Daly...................4

History of Rome--Livy (V. Warrior trans)..........................................4

Who's Who in Classical Mythology--Michael Grant & John Hobbs...4

15. The Best From Fantasy & Science Fiction (Ace Books 1955)...........2

Cliff's Notes to Virgil's Aeneid.............................................................2

17. Encyclopedia of Greco-Roman Mythology--Jessie M. Tatlock...........1

The History of Romulus--Jacob Abbott................................................1

Justinian and His Age--P. N. Ure........................................................1

Queen Cleopatra--Talbot Mundy.........................................................1

The Spirit of the Age--William Hazlitt.................................................1

Those books that had received no reviews are The Holmes Reader--Oliver Wendell Holmes (Oceana), The Battle of Marathon: A Poem--Elizabeth Barrett (pre-Browning), Letters From Turkey--Mary Worley, Scenes From Virgil--Rev. A. J. Church, Beeton's Classical Dictionary, Companion to Roman Religion (J. Ruoke, ed.), Pompeii: Its Life and Art--August Mau, Chaucer--G. K. Chesterton, Schooplearning Guide to the Aeneid, Virgil's Aeneid: Cosmos and Imperium--Philip Hardie, Heroes & Heroines of Greece and Rome (auth?), and Stories of the Old World, by the Rev A. J. Church, who makes a second appearance in this challenge, but suffers the indignity of the shutout on both occasions.

This is a solid winner. I already have a copy of the Edith Hamilton book, which is a bit of a classic of its kind, though I have never read it. I am always embarrassed by how little I know, or can remember,of the Greek myths. I have actually been picking up a little in the last year or so, since my wife has been teaching her Greek classes and has been introducing some of the art and mythology into those. It is the kind of thing that it cannot hurt me to review. I still like art and poetry, or want to like them, and a sizable chunk of the collective body of these pursuits in our civilization is based on these myths. You cannot get very far in understanding these areas without a halfway decent knowledge of them (the myths).

The challenge produced one film contender:

1. Troy.............999

I'll put it at the bottom of my queue.

This was my fourth time reading the Aeneid (in English, obvs). I have used a different translation each time. Back in school I read the Rolfe Humphries, the Robert Fitzgerald a couple of years afterwards, the Fairclough (Loeb edition), and on this last occasion, the J.W. Mackail (Modern Library). These last two are prose translations. I own the Britannica Great Books edition of the poem, which has a verse translation by James Rhoades. Maybe I will find a reason to take that up in another ten years. There is also a Dryden translation which emits something of a classic aura, however accurate or poetically good it happens to be. The Robert Fagles seems to be considered the best of the modern efforts, and as in the art of translation consensus seems to be that there has been a steady progression over the centuries that continues into our own time, that would make it de facto the best in existence. As with most artistic or intellectual productions I have a hard time warming up to anything too contemporary, that might be alive in some way that has eluded me and therefore will be threatening to my self-esteem, I find I am not overeager to read it. I always even found Fitzgerald's translations, of Homer as well as Virgil, to be too informed by something I vaguely define as modern academic triumphalism, and he goes all the way back to the 60s. At the same time the prose translations, however old they are, are not wholly satisfying either. My favorite is still Rolfe Humphries's, originally published in 1951 and part of the Scribner Library. I know that the associations from the time that I read it, as well as the freshness of reading classic literature and the crazy but aesthetic attractive hopes that the undertaking represented, is coloring my memory, but after all it is precisely this sort of coloring in the midst of (in my instance blushingly tepid) youthful excitement that informs who most of are. That said, Humphries had something of that spare but forceful mid-century style that seems to suit the style and spirit of this poem--or at least what I want the style and spirit of this poem, and most classic literature--to be. Unfortunately I lost my copy of it some years ago or I would give a sample passage.

(According to Wikipedia, Rolfe Humphries was born in Philadelphia in 1894 and died in California in 1969. He was a graduate of Amherst College. Though he was a poet and published in Harper's and the New Yorker in addition to doing his Aeneid translation, he taught Latin in secondary schools until 1957. It is not uncommon in books published before 1960 to find authors or contributors whose titles are "English Department Chairman, Central High School" or the like (though I suspect Humphries probably taught at more exclusive private schools). W. H. Auden called his Aeneid 'a service for which no public award could be too great".

As with Faulkner and,, I am beginning to sense, many of the Great Books, The Aeneid is more or less impossible to read when you are tired or at all distracted. This is a big problem for me, since I rarely have the opportunity to read when I am not tired, and never when I am not distracted. At night, which is when I do, or was planning to do, most of the reading for this program, I usually could not get through more than two pages before my head would begin lolling, I would completely forget where I was, sentences begun would get lost in the mush of my brain and run on into completely nonsensical strings of words, and the book would fall out of my hands (Such is the sad fate to which the failed scholar comes in the end; but I digress). So it took me much longer to read the poem than would seem reasonable. I was averaging 5-7 pages (or about a third of one Book of poetry) a day. When I could stay awake and concentrate long enough to build some momentum and become immersed in the act of reading the book, I felt some of the old enjoyment and happy associations that come even with reading accounts of ancient bloodbaths; thoughts of Italy and the Mediterranean World, of the saga of Western Civilization, now in our own lifetimes apparently dying, in its handsome boyhood, of the destinies of great nations and men, images of my own youth, of clouds slowly drifting across the blue sky of a sunny day when one had all the time and possibility in the world. Of course the primary content of the book if one pays any attention to it, especially in a prose translation, is war and death, in the service of a glorious cause, or several of them perhaps, but nonetheless life and dignity, where the ordinary individual is concerned, is less than cheap. In youth one always identifies with the writer, and the triumph of his vision and art and the strongest of the creations he has employed in the service of this. Greatness and achievement, we think, are often by necessity messy, but no man worthy of the name would suffer to endure life as a mediocre or inferior person anyway. In middle age however, especially in the state of semi-delirium that is the attempt to read late at night, such passages read like this:

"...Next the great meritocrat levelled his spear full on (Bourgeois Surrender) from far...(Surrender), clasping his knees, speaks thus beseechingly...'I entreat thee, save this life for a child and a parent...The victory of Big Money Enterprises does not turn on this, nor will a single life make so great a difference.' (Surrender) ended...The Global Champion grasps his helmet with his left hand, and bending back his neck, drives his sword up to the hilt in the suppliant..."

or

"...(Surrender), slipping down from the chariot, pitiably outstretched helpless hands: 'Ah, by the parents who gave thee birth, great Investor, spare this life and pity my prayer.' More he was pleading, but the Investor, who was also a cardiac surgeon, an attorney, a best selling author and a former Olympic medalist: 'Not such were the words thou wert uttering (before I was present) Die...' With that his sword's point pierces the breast where the life lies hid."

I had wanted to finish the book before my vacation in Florida in order to have something a little less stodgy (and more practical with children) to read on the beach. My slow pace prevented this from being realized however, as I could only get to the middle of Book Ten by the time of my arrival. This actually would not be a bad beach read if one were left unmolested even for a couple of hours a day. I think I only managed to get through about fourteen pages in a week as it was however, and I did not finally finish the book until I got back to New Hampshire.

I have not talked much about he actual book. It is emotional for me, as all of the undisputed canonical books and authors are, because I felt at point in my life to have some connection to this strain of life, that it was in reach for me. It wasn't, so there is a lot of sadness and feelings of pointlessness as trying to revisit them now, but at the same time it evokes images and thoughts from, if not a happier, at least a period of life when one felt the possibility of someday being alive and playing a serious role somewhere in the world.

The Bourgeois Surrender Challenge

The winner of the last challenge, Kobo Abe's Woman in the Dunes, I am reading now, and am about 2/3rds of the way through. I was hoping to read this at the beach if I had finished Virgil, but seeing as the book is a Kafka/Beckettesque story about a man who is unwittingly entrapped in a hole surrounded by fifty foot sand cliffs from which it is impossible to escape, maybe I am glad I did not. It is supposed to be one of the premier Japanese novels of the 20th century, according to my early 90s era Vintage Press paperback copy (they're on the level, right?) Perhaps the translation is inadequate--I remember reading some complaint recently that English translations of Japanese literature were notably weak--but I find the book to be rather thin. Maybe it has one of those remarkable endings that pulls all the seemingly minor incidents and specified objects of the book together. I suppose there is a sense of fineness and of seemingly small things being more significant than or the essential part of bigger things that I think of as characteristically Japanese. But at the moment, on page 156 of 241, I want more of something, not action necessarily, but personality, or demonstration of brain power. Maybe it is too subtle for me and everything I say I want is there, if you can find it (though if this is the case it is really subtle).

On page 136 Abe did get around to writing about sex. This part I think I am clear on:

"Food exists only in an abstract sense for anybody dying of hunger; there isn't any such thing as the taste of Kobe beef or Hiroshima oysters. But once one's body is full, then one begins to discern differences in taste and textures..."

This part lost me though, I have to admit:

"...sex couldn't be discussed in general; it depended on time and place...sometimes you needed a dose of vitamins...sometimes a bowl of eels and rice. It was a well thought out theory, but regrettably not a single girl friend had offered herself to him in support of it, with a readiness to experience sexual desire in general or even in particular. That was natural. No man or woman is wooed by theory alone. He knew this, but he naively observed the theory of the Mobius circle and kept repeatedly pushing the doorbell of an empty house, only because he did not want to commit spiritual rape."

The book is worth finishing, and I am curious to see where it is going after all. I would like to see the movie of it too. I can see where that might be interesting.

The Bourgeois Surrender Challenge

Many of the magic words used in this challenge were too blatantly Aeneid words, so our searches turned up an inordinate number of books with a classical theme about them somewhere. There were also an impressive number of titles by very celebrated authors (Oliver Wendell Holmes, E. B. Browning,Chesterton, Hazliit) with zero or one ranking.

1. Mythology--Edith Hamilton.............................................................267

2. A Grave Talent--Laurie R. King........................................................69

3. The Rise of Rome--Anthony Everitt....................................................59

4. The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes--Conan-Doyle...........................46

5. Age of Bronze (The Story of the Trojan War) Betrayal--Shanower...10

Deadlock--James Reasoner................................................................10

7. Makers of Ancient Strategy--Victor Davis Hanson (ed.).....................9

8. Canadian Adventures of Sherlock Holmes--Stephen Gaspar...............6

McGuffey's Primary Eclectic Primer...................................................6

10. Cassell's Dictionary of Classical Mythology--Jenny March..............5

Encyclopedia of Greco-Roman Mythology--Mike Dixon-Kennedy...5

12. Greek and Roman Mythology A to Z--Kathleen N. Daly...................4

History of Rome--Livy (V. Warrior trans)..........................................4

Who's Who in Classical Mythology--Michael Grant & John Hobbs...4

15. The Best From Fantasy & Science Fiction (Ace Books 1955)...........2

Cliff's Notes to Virgil's Aeneid.............................................................2

17. Encyclopedia of Greco-Roman Mythology--Jessie M. Tatlock...........1

The History of Romulus--Jacob Abbott................................................1

Justinian and His Age--P. N. Ure........................................................1

Queen Cleopatra--Talbot Mundy.........................................................1

The Spirit of the Age--William Hazlitt.................................................1

Those books that had received no reviews are The Holmes Reader--Oliver Wendell Holmes (Oceana), The Battle of Marathon: A Poem--Elizabeth Barrett (pre-Browning), Letters From Turkey--Mary Worley, Scenes From Virgil--Rev. A. J. Church, Beeton's Classical Dictionary, Companion to Roman Religion (J. Ruoke, ed.), Pompeii: Its Life and Art--August Mau, Chaucer--G. K. Chesterton, Schooplearning Guide to the Aeneid, Virgil's Aeneid: Cosmos and Imperium--Philip Hardie, Heroes & Heroines of Greece and Rome (auth?), and Stories of the Old World, by the Rev A. J. Church, who makes a second appearance in this challenge, but suffers the indignity of the shutout on both occasions.

This is a solid winner. I already have a copy of the Edith Hamilton book, which is a bit of a classic of its kind, though I have never read it. I am always embarrassed by how little I know, or can remember,of the Greek myths. I have actually been picking up a little in the last year or so, since my wife has been teaching her Greek classes and has been introducing some of the art and mythology into those. It is the kind of thing that it cannot hurt me to review. I still like art and poetry, or want to like them, and a sizable chunk of the collective body of these pursuits in our civilization is based on these myths. You cannot get very far in understanding these areas without a halfway decent knowledge of them (the myths).

The challenge produced one film contender:

1. Troy.............999

I'll put it at the bottom of my queue.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/51392507/HelenRosner_IMG_8932.0.0.jpg)