B List: Between books

C List: John Steinbeck--East of Eden...................................................215/601

While Edith Wharton is a capable enough writer, she is also very much after the manner of Henry James, albeit without some of the density, and I find that going deeper into her oeuvre, at least at this stage of my life, is bringing diminishing returns with regard to pleasure. This book is in much the same vein as The Custom of the Country, and both of these share an obvious bloodline with The Age of Innocence, which I remember writing some complimentary things about at the time I read it. This one is probably not bad for what it is, I just am not finding it to be interesting at this time.

Now East of Eden, on the contrary, I am enjoying a great deal. Remarkably, I had never read any Steinbeck before, even Of Mice and Men, which is still widely read in the schools. This is the kind of book that I was raised on, so to speak, in my earliest forays into literature as a teenager, and it is comfortable to me as far as pace, length, character development and so forth. Whenever I take it up (so far) I never fail to find it interesting, nor do I find myself falling asleep or my concentration drifting when I try to read some in the evening, which is an increasingly important consideration. So it is always exciting to have a book like that going, especially when it has some claim to being a classic, even a minor one or one with a lot of contingencies attached to it. I hope it keeps up.

It's hard to believe that a little more than a hundred years ago central California was barely inhabited. I have never been to California. I still imagine I will make it out there someday, but the years keep going by and there is no real opportunity to take that trip in sight anywhere on the horizon.

One more week and I will have gotten to the end of what has been a very long and particularly grueling school year, after which I'll have 2 1/2 months to try to recover and get ready to survive the next one. Only two more years until people start going to college. Having done essentially no planning for this, as was the case with myself as a youth, though in a somewhat different time when getting through a regular college experience was still reasonably manageable for a middle class person with by traditional standards adequate academic credentials, I can only imagine what that is going to be like.

A lot of pretty girl pictures this month. We should try to include some more serious, or at least artistic pictures too.

The character played by James Dean in the movie is still an infant at the part I am at in the book, which I think bodes well for my continued interest in the story.

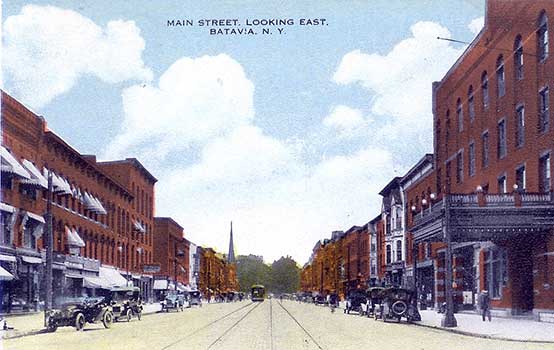

America.

_-_1.jpg)