The literary editors of the Illustrated World Encyclopedia write in their introduction to this book that "To the student of the novel almost no novel can be more important than The Awkward Age." This book is widely considered to belong to the transitional phase of James's later career that culminated in the three final masterpieces of the first half-decade of the twentieth century, The Wings of a Dove, The Ambassadors, and The Golden Bowl. It seems to me after reading it that it can be characterized pretty safely with this group, all of which I have at least read through, with varying degrees of success, The Golden Bowl being the one I would consider to have been the most satisfactory experience, in that it is the one I found the least wearying to get through. Given my longtime aspirations to be acceptably well-versed in literature above any other area of study, these great late Henry James novels have always been something of an obstacle to my satisfaction on this point. I have been convinced by enough of those Who Really Know of the importance, masterful construction, and, perhaps rarest of all, the highly satisfying mature intelligence at work in them, that to not be fully immersed in the experience of all of these qualities in the course of one's reading is to be dogged by a persistent sense of failure that one is ultimately unable to overcome. It is like keeping up in a difficult course at school. The determination may be there at the beginning and the persistence may not flag entirely, but once you lose the thread in any part there is no keeping up and it is impossible to fully rejoin the pursuit with any degree of mastery because everything significant in the story is dependent on and follows precisely from the various difficult and opaque scenes that have accumulated before it.

Keeping in mind that James's high seriousness and maturity are the qualities his fans admire above all, I nonetheless felt compelled to make a note that this was an actual paragraph in the book (p.91):

"The old man had got up to take his cup from Vanderbank, whose hand, however, dealt with him on the question of sitting down again. Mr Longdon, resisting, kept erect with a low gasp that his host only was near enough to catch. This suddenly appeared to confirm an impression gathered by Vanderbank in their contact, a strange sense that his visitor was so agitated as to be trembling in every limb. It brought to his lips a kind of ejaculation--'I say!'"

p. 96 Another classic Henry James sentence:

"Poor Mitchy's face hereupon would have been interesting, would have been distinctly touching to other eyes; but Nanda's were not heedful of it."

The prominent blogger Tyler Cowen once opined that Dostoevsky had become tiresome to read in our time because his concerns were not our concerns (though I don't think I personally qualify as part of the collective "our" referenced here). I often find myself having to ask "Are Henry James's?"

p. 173 On the salon-like atmosphere at Mrs Brookenham's:

"The men, the young and the clever ones, find it a house--and heaven knows they're right--with intellectual elbow-room, with freedom of talk. Most English talk is like a quadrille in a sentry box. You'll tell me we go further in Italy, and I won't deny it, but in Italy we have the common-sense not to have little girls in the room."

It certainly seems as if our time is suffering for a lack of "intellectual elbow-room".

p. 281 "The pause she thus momentarily produced was so intense as to give a sharpness that was almost vulgar to the little "Oh!" by which it was presently broken and the source of which neither of her three companions could afterwards in the least have named. Neither would have endeavoured to fix an indecency of which each doubtless had been but too capable."

My comment on the above passage: "Subtle, oh yes, but at some point you wouldn't mind seeing a neutron bomb detonated in the middle of these people."

p. 309 "Edward's gloom on this was not yet blankness, yet it was dense."

I am groaning at this point.

As I have mentioned somewhere in these blogs, I was afflicted by a kidney stone around the middle of this book, and the accompanying abdominal pain made it impossible to read for several days until I was put on some opioid pain medicine, which I actually found to be a great aid to concentration on the book during the days I was on it leading up to my operation. I don't know what it says for Henry James however that the optimal conditions for enjoying his later work in the 21st century may be to be hopped up on painkillers and largely confined to bed for the better part of a week.

I have not generally found editions of most Henry James novels from my preferred 1920-1970 period to be especially thrilling, so I opted to go with a fairly recent (1993) reprint from the Everyman series. This included a 25 page introduction by Cynthia Ozick which I read about a page of before determining that I was not going to find it helpful to understanding the book any more than I actually did.

By completing this I have now come to the end of the literary classics selection for volume 2 of the encyclopedia, as well as finally coming to the end of the "A" titles. It took slightly more than four years to accomplish this, though the "As" do represent about 10% of the entire list. I am still on pace to not finish the entire list until I am 83 however, so eventually I am going to have to pick it up a little. I believe once my children are older--I still have a two year old at the moment--that I will be able to do that.

The Challenge

1. Joe Hill--Twentieth Century Ghosts...........................................................474

2. Father Jonathan Morris--The Promise........................................................146

3. Michelle Paige Holmes--Yesterday's Promise...........................................116

4. Arthur Conan Doyle--The Return of Sherlock Holmes................................88

5. Petra ten-doesschate Chu--Nineteenth Century European Art....................28

6. Steven Levingston--Kennedy and King.......................................................26

7. Elizabeth Bowen--The Hotel.........................................................................7

8. Henry C Dethloff & John A. Adams--Texas Aggies Go to War...................1

9. Genderuwo (movie).......................................................................................0

10. Eric Harrison & Kendall Johnson--Critical Companion to Henry James...0

11. Henry James's Europe: Heritage and Transfer (ed. Harding).....................0

12. Miss Desirable--A Little Bit of Taani...........................................................0

1st Round

#5 Chu over #12 Desirable

I'm not sure if Desirable is an actual book or not.

#6 Levingston over #11 Henry James's Europe

#7 Bowen over #10 Harrison and Johnson

It's tough to earn a win coming in with 0 points against any kind of remotely serious book.

#9 Genderuwo over #8 Dethloff and Adams

Genderuwo is a 2007 Indonesian film that is all accounts quite dismal, but it has an upset on reserve in its account for this tournament.

Final 8

#1 Hill over #9 Genderuwo

#7 Bowen over #2 Morris

Father Morris is a regular contributor to Fox News, mainly as an authority on religious matters. He is also a campus minister at Columbia University, for what it's worth. Bowen's book, though not exceptionally well known, at least in this country, seems to be considered to have literary value. A handsome edition of it was published by the University of Chicago press in 2012.

#3 Holmes over #6 Levingston

None of Holmes's books are carried by any libraries, presumably because she is a romance novelist. But she had an upset coming in the tournament.

#4 Doyle over #5 Chu

The literary blue blood Doyle prevails over the game art expert in a well-played match.

Final Four

#1 Hill over #7 Bowen

The 45 year old author Joe Hill, a native of Bangor, Maine, seems to be the relatively incognito son of mega best-selling author Stephen King. My inclination would have been to favor Bowen's neglected-but-in-some-quarters-respected novel here but those designated upsets come into play.

#4 Doyle over #3 Holmes

Amusing coincidence in the name of Doyle's opponent.

Championship

#1 Hill over #4 Doyle

In overtime. Doyle does have at least two books on the official list, The Hound of the Baskervilles and A Study in Scarlet, so he will not be neglected. The main purpose of the whole "C" list being to expose myself to more contemporary or neglected literature and authors where plausible, Hill seems plausible enough to get the victory here.

Tuesday, January 16, 2018

Tuesday, January 9, 2018

January 2018

A List: Charles Dickens, Martin Chuzzlewit.............................157/841

B List: Between books at present

C List: Knausgaard, Volume 4..................................................464/502

Still trying to finish a report for the B list.

This is a new Dickens for me, and so far it seems to me a worthy enough addition to his oeuvre. The humor and the ingenious hyperbolic sentences and descriptions are as prominent and entertaining as ever. I don't know whether it is because I am too distracted when I read these A-list books or not but I am having a little trouble getting immersed enough to keep the thread of the plot and the various relationships and romantic interests straight. This may also be the reason however why this particular book is not usually considered with the top rank of Dickens's novels, as it otherwise shares what I usually find to be their best characteristics.

When I was reading the Henry James that absorbed so much of my mental energy I largely put Knausgaard aside for several weeks. However on picking him up again in the interval between B books I have been able to come near to finishing it pretty quickly. My opinion on him is consistent with what I have written elsewhere. He is interesting enough and smart enough that I keep reading him, obviously, though the action is really quite commonplace and doesn't lead to anything Important or mind-changing, which I suppose is what we are supposed to be looking for. This volume centers on Knausgaard's teenage years, and at 18 he has still not successfully completed coitus with a woman, but he has been in bed naked with a lot of women, five or six at least, and made out with several more. He was definitely part of the sensual world with opportunities bursting upon him at seemingly every turn. (I was not. I was not. I was not. I was not. I was not. I wa.........)

I probably won't be getting to volume 5 for a while now, as I have 3 C-list books waiting in the queue, plus I got a modern book for Christmas that I intend to try to read in the Knausgaard spot, i.e., when I come to a point where I have finished a C-list book without the next one lined up.

Pictures?

Out of time this month.

B List: Between books at present

C List: Knausgaard, Volume 4..................................................464/502

Still trying to finish a report for the B list.

This is a new Dickens for me, and so far it seems to me a worthy enough addition to his oeuvre. The humor and the ingenious hyperbolic sentences and descriptions are as prominent and entertaining as ever. I don't know whether it is because I am too distracted when I read these A-list books or not but I am having a little trouble getting immersed enough to keep the thread of the plot and the various relationships and romantic interests straight. This may also be the reason however why this particular book is not usually considered with the top rank of Dickens's novels, as it otherwise shares what I usually find to be their best characteristics.

When I was reading the Henry James that absorbed so much of my mental energy I largely put Knausgaard aside for several weeks. However on picking him up again in the interval between B books I have been able to come near to finishing it pretty quickly. My opinion on him is consistent with what I have written elsewhere. He is interesting enough and smart enough that I keep reading him, obviously, though the action is really quite commonplace and doesn't lead to anything Important or mind-changing, which I suppose is what we are supposed to be looking for. This volume centers on Knausgaard's teenage years, and at 18 he has still not successfully completed coitus with a woman, but he has been in bed naked with a lot of women, five or six at least, and made out with several more. He was definitely part of the sensual world with opportunities bursting upon him at seemingly every turn. (I was not. I was not. I was not. I was not. I was not. I wa.........)

I probably won't be getting to volume 5 for a while now, as I have 3 C-list books waiting in the queue, plus I got a modern book for Christmas that I intend to try to read in the Knausgaard spot, i.e., when I come to a point where I have finished a C-list book without the next one lined up.

Pictures?

Out of time this month.

Friday, December 8, 2017

December 2017

I am a couple of days late with this month's check-in. The 6th was my 20th anniversary, and yesterday I was very tired. My reading has also slowed a bit due to the nature of some of the works, but you still make some progress even doing a minimal amount every day.

A List: George Eliot--Silas Marner............................................................106/134

B List: Hank James--The Awkward Age.....................................................130/393

C List: Knausgaard, Volume 4...................................................................164/502

It is my first time for all of these. Silas Marner is different from what I was expecting, and I am not entirely sure what I make of it yet. It is well-plotted and is a fairly good read to this point, except for the parts when she has rustics speaking in dialect. I still do not foresee the conclusions of the various threads of the plot. It is a moral work, and one that thus far seems to me to adhere pretty closely to standard 19th century Protestant attitudes, coming down against dishonesty, especially in one's dealings with the community, and profligacy, though the other extreme of profligacy, miserliness, is contrasted with as something of an overreaction, if not quite as utterly wicked.

I write a lot here about my need increasingly to be well-rested and fairly when reading certain authors, most of whom seem to be Victorians of one kind or another, though whether this is due to age, a continuous lack of good sleep, or the effects of the internet and other developments of modern life rotting my brain, I don't know. Henry James of course, especially in his later period (and while in the Awkward Age he has not fully arrived there, it is perhaps the key novel in the transition to it), is the king of writers who require a clear mind and an hour or two with no serious distractions to read with any comprehension. After the first couple of days I had to give up reading him at the end of the day entirely, because it was impossible. I have read a lot of Henry James over the years--eight or nine of the longer novels, a couple of stories, two novelettes (I'm counting Aspern Papers and Turn of the Screw in this category), The Art of Fiction--and I have developed a certain affection for him, though he can be very precious, especially in his much-loved (by very serious and mentally sophisticated people) later books. So far the entire novel of The Awkward Age consists of people sitting in drawing rooms testing each other with conversations and expressions refined to a microscopically fine subtlety. It doesn't look like any other setting or kind of action is going to be introduced any time soon, though the scene does shift every thirty pages or so to a different day and a different drawing room and different combinations of people. I want to like it, and depending on how receptive my mind is on a given day I generally do like it, but the truth, or more to the point, the higher truth and necessity of the later James continues to ultimately elude me I fear.

I started the Knausgaard in the interval between the B-List books while doing the Oliver Wendell Holmes write-up, but I've largely put it down for the past week in order to devote my limited energy to wrestling with the James. Thus far I feel largely the same about him as I have noted here in other postings, I like the books, the writing is personable and intelligent and it really does take me back to my own teen-age years, which, while I admit my prejudice, definitely strike me as a freer and more fun time to be a teenager than now, as well as more conducive to extended concentration and thinking, however unfavorably that period compared to epochs that had come before it. How much time did we used to spend listening to the same ten record albums over and over? This is certainly something people don't do any more.

I was going to put up an old picture commemorating my 20th anniversary, which would not be horribly out of place among these other pictures of beautiful young people, but I didn't get around to it.

A List: George Eliot--Silas Marner............................................................106/134

B List: Hank James--The Awkward Age.....................................................130/393

C List: Knausgaard, Volume 4...................................................................164/502

It is my first time for all of these. Silas Marner is different from what I was expecting, and I am not entirely sure what I make of it yet. It is well-plotted and is a fairly good read to this point, except for the parts when she has rustics speaking in dialect. I still do not foresee the conclusions of the various threads of the plot. It is a moral work, and one that thus far seems to me to adhere pretty closely to standard 19th century Protestant attitudes, coming down against dishonesty, especially in one's dealings with the community, and profligacy, though the other extreme of profligacy, miserliness, is contrasted with as something of an overreaction, if not quite as utterly wicked.

I write a lot here about my need increasingly to be well-rested and fairly when reading certain authors, most of whom seem to be Victorians of one kind or another, though whether this is due to age, a continuous lack of good sleep, or the effects of the internet and other developments of modern life rotting my brain, I don't know. Henry James of course, especially in his later period (and while in the Awkward Age he has not fully arrived there, it is perhaps the key novel in the transition to it), is the king of writers who require a clear mind and an hour or two with no serious distractions to read with any comprehension. After the first couple of days I had to give up reading him at the end of the day entirely, because it was impossible. I have read a lot of Henry James over the years--eight or nine of the longer novels, a couple of stories, two novelettes (I'm counting Aspern Papers and Turn of the Screw in this category), The Art of Fiction--and I have developed a certain affection for him, though he can be very precious, especially in his much-loved (by very serious and mentally sophisticated people) later books. So far the entire novel of The Awkward Age consists of people sitting in drawing rooms testing each other with conversations and expressions refined to a microscopically fine subtlety. It doesn't look like any other setting or kind of action is going to be introduced any time soon, though the scene does shift every thirty pages or so to a different day and a different drawing room and different combinations of people. I want to like it, and depending on how receptive my mind is on a given day I generally do like it, but the truth, or more to the point, the higher truth and necessity of the later James continues to ultimately elude me I fear.

I started the Knausgaard in the interval between the B-List books while doing the Oliver Wendell Holmes write-up, but I've largely put it down for the past week in order to devote my limited energy to wrestling with the James. Thus far I feel largely the same about him as I have noted here in other postings, I like the books, the writing is personable and intelligent and it really does take me back to my own teen-age years, which, while I admit my prejudice, definitely strike me as a freer and more fun time to be a teenager than now, as well as more conducive to extended concentration and thinking, however unfavorably that period compared to epochs that had come before it. How much time did we used to spend listening to the same ten record albums over and over? This is certainly something people don't do any more.

I was going to put up an old picture commemorating my 20th anniversary, which would not be horribly out of place among these other pictures of beautiful young people, but I didn't get around to it.

Tuesday, November 28, 2017

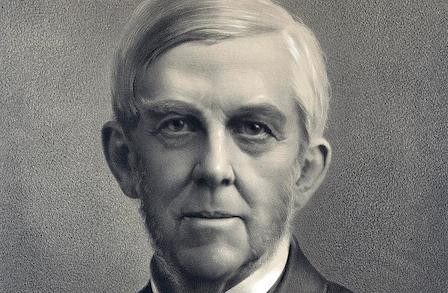

Oliver Wendell Holmes--The Autocrat of the Breakfast Table (1858)

While I liked it, I have to say this is an odd book to take up in 2017. I'm not sure that I will remember anything about it a week from now other than such things as have a direct resonance with me--in this instance the importance of breeding and the need in a young man to have a tireless ambition and drive. Much of the other incidental stuff was not terribly vivid to my mind. Writing in the 1960s, the IWE editor says of the book that it "is generally considered Holmes's masterpiece (which suggests the presence of other contenders. I have actually read his equally florid novel Elsie Venner, if that is one of the contenders the writer has in mind). The introduction goes on to say that "The humor, urbanity, iconoclasm and scholarship of the essays are almost unique for their times and are timeless, being as good reading today as then." As a indicator of how much times have changed, it is almost impossible for me to imagine anyone with credibility saying anything like this today. Once again one is reminded of the question I have often had occasion to ask here, where have all the old Yankee/WASPs gone, even in New England? There were still some around in my youth in the 80s, and in books and articles about the region even from that time the character is still highly prominent compared to now. Have those that are left gone way underground (or over-ground, as the case may be)?

The copy of the book that I bought (online) was a special boxed edition published in 1955 by the Heritage Press of Norwalk, Connecticut, with an introduction by Holmes' fellow super-Brahmin Van Wyck Brooks and nostalgia-inducing pen and ink illustrations by R. J. Holden. It is noted in the introduction that no less a figure than Henry James, Sr (father of the famous philosopher and novelist brothers) called Holmes "the most intellectually alive man I ever knew". Indeed, Holmes's mind was by all accounts the type which the higher sort of formal education once sought to cultivate, yet it is hard to imagine him being broadly admired in this way today, mainly because of his race/gender/caste/ethnicity combination, since his primary sins (social and intellectual snobbery, ethnic chauvinism) are not exactly absent among the classes correspondent to his today, though it seems to be a more intolerable trait when found in a person like Holmes. There is also the problem that however impressive his mind was to his contemporaries, it led him to hold a lot of social views that are not currently held to possess much intelligence, let alone any other value, which naturally throws the quality of the other facets of his mind under suspicion.

It is noted that the takedown of Holmes and the other old Yankee writers began at least as far back as Mencken and the rise of ethnic America, which I guess would include my people, a period now a century in the past.

After the Brooks introduction there are three prefaces written by Holmes himself for each of the three editions that came out in his lifetime, the original in 1858, the later ones in 1882 and 1891, at which latter dates Holmes was 82 years old. These prefaces are consistent in their emphases on technological and scientific progress, which were of course immense over the course of his career (1831-91, roughly, as well as social progress, which he hinted in 1891 of having expectations of great changes in that area in the 20th century, though he did not speculate on the specific forms they might take). He was progressive and elitist at the same time, his progressivism taking the form of believing in the possibility of uplifting the unenlightened peoples of the world to the Anglo-Saxon level, or some facsimile of it. I wrote "we'll see if he lists his views on the potential/proper role for women in the book proper." I don't recall anything worth noting on this matter coming on, but that is why I take notes, because I remember very little of what I read.

p. 1 "We are mere operatives, empirics, and egotists, until we learn to think in letters instead of figures." Of course I want to believe this. Whatever it is, something is missing from the data driven understanding of existence as concerns achieving some sense of wholeness as a human being

.

p. 4 On the virtue of mutual admiration societies of high achieving males: "Foolish people hate and dread and envy such an association of men of varied power and influence, because it is lofty, serene, impregnable, and, by the necessity of the case, exclusive." Do foolish people have a choice in the matter, so far as their essential foolishness can be effected?

I am already noting at this early stage that the book looks to be extremely quotable throughout. Then I wrote that the thinking people (illegible) who have (illegible) lost their taste for this sort of writing seem to think/live after a similar manner.

It's hard to get a cute girl picture to come up in a search for OWH Autocrat, etc, but this Boston duck boat driver will do.

I write my illegible notes in the book in pencil, in which I am hindered by the circumstance that my pencil sharpener does not evenly sharpen the pencils and makes them difficult to write with. I know that there are myriad easy ways to correct this situation, but nothing is really easy with me when it comes to trying to carry out some semblance of the life of the mind. I will never quite permanently solve my pencil problem, or my note taking problem, or my slow writing problem, or any other minor and irritating problem that besets me.

I forgot about when Holmes by way of establishing the mental climate out of which the book arose, introduced it as a world where most people listened to a hundred sermons a year.

Holmes likes a man of family. This hurts for me, since a lot of the more intelligent modern people seem to like that too, and the family that I came out of at least doesn't seem to excite anybody very much. He reverts to this theme several times in the course of the book, lamenting mésalliances in marriage between people whose backgrounds and breeding are not well matched. "No. my friends, I go (always, other things being equal) for the man who inherits family traditions and the cumulative humanities of at least four or five generations."

p. 43 "The woman who calc'lates is lost...Put not your trust in money, but put your money in trust." On matrimony. My poor wife trusted...So much so that she has said that if she were ever to remarry, it would only be for money.

p. 45 "Except in cases of necessity, which are rare, leave your friend to learn unpleasant truths from his enemies; they are ready enough to tell them."

p. 46 "Therefore conversation which is suggestive rather than argumentative, which lets out the most of each talker's results of thought, is commonly the pleasantest and the most profitable." Yes, but we must be convinced that our interlocutor is not an absolute dunce who is even capable of saying anything worth our listening to, which is rare in our time.

p. 54 "How many people live on the reputation of the reputation they might have made!" Not many anymore I wouldn't think. We've set ourselves with some dedication to snuffing out that kind of conceit.

p. 54 "When one of us who has been led by native vanity or senseless flattery to think himself or herself possessed of talent arrives at the full and final conclusion that he or she is really dull, it is one of the most tranquillizing and blessed convictions that can enter a mortal's mind." Yes and no. It may be liberating to an extent for the non-genius himself to realize his limitations, and it is certainly applauded by all the people who were annoyed by his ridiculous pretensions, but the people he has close relationships with who rely on him to some degree do not happily welcome the definitive proof that their fortunes are chained to a dullard with little prospect of improvement.

This is essentially the edition of the book I have, though instead of this teapot I have a red rectangle with a gold border and the initials O.W.H. imprinted on the field in gold letters.

p.58 There was a reference to news from India which was unclear to me, but a little research indicates that he must be referring to the Sepoy Rebellion of 1857. I am so conditioned to assume that insightful and adroit minds even in the past must have at some level been suspicious of the virtues of European colonialism (and certainly some were), that I thought that perhaps Holmes's references to unidentified women and children being outraged and babies being killed were oblique statements against British conduct, and that his referring to the Indians as the inferior race was ironic. But no, he was taking the pro-English position all the way.

Holmes ascribes powers to genuine (high) poetry and its relations/interactions with human souls that may contain some truth, but are largely foreign to the way almost everyone intelligent experiences life now.

He also makes an interesting mechanical comparison of the making of a poem to that of a fine violin, that time is necessary to dry out and fit together the many parts of which it is composed to produce the grand effect.

p. 146 I like the account of his morning rowing around Boston.

Holmes's own poems are interspersed throughout the book. They are for the most part not very good, difficult to read and scant on impressions and images. There are two poems that are moderately famous, or used to be, "The Chambered Nautilus", and "The Wonderful One-Hoss Shay", the latter a comic poem, that are markedly better than the rest.

p. 171 Holmes on people who smile stupidly for no good reason in social interactions: "...it is evident that the consciousness of some imbecility or other is at the bottom of this extraordinary expression. I don't think, however, that these persons are commonly fools. I have known a number, and all of them were intelligent. I think nothing conveys the idea of underbreeding more than this self-betraying smile." Underbreeding seems to me a useful concept that is not discussed nearly enough in our time.

He muses on how "there is no looking glass for the voice", such that people have no real sense of the sound of their own voices, and how pleasant it would be to be able to inhabit another form and be able to observe oneself speaking and moving. (Of course the technology to do this had not yet been developed in the 1850s).

There is a long and pleasant section about the trees of New England which is perhaps of greater interest if one happens to live here. Holmes notes many particular favorites and claims to "have as many tree-wives as Brigham Young has human ones." The loss of our elm trees was such a blow to New England's historical character. Holmes mentions them extensively, as does almost everyone who writes about the region prior to World War II.

Holmes sees the English and American varieties of elms as characteristic of the creative force of the respective countries. The English he describes as "compact, robust, holds its branches up, and carries its leaves for weeks longer than our own native tree", and the American as "tall, graceful, slender-sprayed, and drooping as if from languor." How this is related to the creative force of America especially I am hazy on.

pp. 261-2 "Qu'est-ce qu'il a fait? What has he done? That was Napoleon's test...Is a young man in the habit of writing verses? Then the presumption is that he is an inferior person. For...there are at least nine chances in ten that he writes poor verses." Common knowledge (sort of) now, but worth being reminded of and impressed on the young.

p. 279 "One's breeding shows itself nowhere more than in his religion."

If you have stuck out this post to this point, I thank you and consider you a true friend. I may not exactly be a tortured soul, but I do feel that I never quite made it as a fully accepted member of the educated classes, and I am lonely in my interests.

The Challenge

1. M. R. Carey--The Girl With All the Gifts.......................................................2,525

2. Haraki Murakami--1Q84................................................................................1,687

3. Tana French--The Secret Place.......................................................................1,663

4. Rachel Macy Stafford--Hands Free Mama.......................................................326

5. Jay Winik--1944: FDR & the Year That Changed History...............................301

6. Rachel Macy Stafford--Hands Free Life...........................................................222

7. D. H. Lawrence--Women In Love......................................................................147

8. John Whyte--Is This Normal? The Essential Guide to Middle Age & Beyond...35

9. Kathleen Ann Goonan--In War Times.................................................................28

10. Germany 1945: The Last Months of the War......................................................0

A small, but pretty strong field for our game, with seven 100+ scoring entrants and the top three seeds all north of 1,500!

1st Round

#7 Lawrence over #10 Germany

The Germany book appears to be a bilingual coffee table book of photographs that was published in Germany and has had no U.S. release. I read Women In Love, which does not appear on the IWE list and therefore qualifies for the Challenge, as the second book on my "A" list way back in December of 1994. It was not my favorite book at the time, though a few years later when I was about 28 I read The Rainbow, which preceded it and follows many of the same characters, and liked it very much, though I don't know if I would feel the same about that one if I read it now either.

#9 Goonan over #8 Whyte.

A close battle. The book about aging was not tempting enough to me to give it the edge here.

Final Eight

#9 Goonan over #1 Carey

Carey is a dreaded genre book. Also my library didn't have it.

#7 Lawrence over #2 Murakami

I was a little excited about the Murakami, which seems to have the status of a contemporary instant classic, but at 925 pages and with a tough matchup in its first game, it falls.

#6 Stafford over #3 French

French is a mega-genre writer, and her book is long. Plus Rachel Macy Stafford is a Generation X (b. 1972) supermom/superwife, Southern Christian variety, and what is not to like about that (if you're me)?

#4 Stafford over #5 Winik

While I acknowledge I have a crush on Rachel Macy Stafford, that is not the whole reason why she triumphs here over a major history. The 1,027 page length of the competitor's offering was what mainly killed it. Jay Winik has a demonstrated fondness for identifying years or even months that changed everything and writing books about them. Another title of his is April 1865: The Month That Saved America.

Final Four

#9 Goonan over #4 Stafford

#7 Lawrence over #6 Stafford

I was feeling guilty about passing over so much literature.

Championship

#9 Goonan over #7 Lawrence

Upset special. The Goonan is another science fiction book, which I have not have good experiences with so far (ed--apart from the Ray Bradbury book; I liked a lot of those stories), but I am willing to give it another try.

The copy of the book that I bought (online) was a special boxed edition published in 1955 by the Heritage Press of Norwalk, Connecticut, with an introduction by Holmes' fellow super-Brahmin Van Wyck Brooks and nostalgia-inducing pen and ink illustrations by R. J. Holden. It is noted in the introduction that no less a figure than Henry James, Sr (father of the famous philosopher and novelist brothers) called Holmes "the most intellectually alive man I ever knew". Indeed, Holmes's mind was by all accounts the type which the higher sort of formal education once sought to cultivate, yet it is hard to imagine him being broadly admired in this way today, mainly because of his race/gender/caste/ethnicity combination, since his primary sins (social and intellectual snobbery, ethnic chauvinism) are not exactly absent among the classes correspondent to his today, though it seems to be a more intolerable trait when found in a person like Holmes. There is also the problem that however impressive his mind was to his contemporaries, it led him to hold a lot of social views that are not currently held to possess much intelligence, let alone any other value, which naturally throws the quality of the other facets of his mind under suspicion.

It is noted that the takedown of Holmes and the other old Yankee writers began at least as far back as Mencken and the rise of ethnic America, which I guess would include my people, a period now a century in the past.

After the Brooks introduction there are three prefaces written by Holmes himself for each of the three editions that came out in his lifetime, the original in 1858, the later ones in 1882 and 1891, at which latter dates Holmes was 82 years old. These prefaces are consistent in their emphases on technological and scientific progress, which were of course immense over the course of his career (1831-91, roughly, as well as social progress, which he hinted in 1891 of having expectations of great changes in that area in the 20th century, though he did not speculate on the specific forms they might take). He was progressive and elitist at the same time, his progressivism taking the form of believing in the possibility of uplifting the unenlightened peoples of the world to the Anglo-Saxon level, or some facsimile of it. I wrote "we'll see if he lists his views on the potential/proper role for women in the book proper." I don't recall anything worth noting on this matter coming on, but that is why I take notes, because I remember very little of what I read.

p. 1 "We are mere operatives, empirics, and egotists, until we learn to think in letters instead of figures." Of course I want to believe this. Whatever it is, something is missing from the data driven understanding of existence as concerns achieving some sense of wholeness as a human being

.

p. 4 On the virtue of mutual admiration societies of high achieving males: "Foolish people hate and dread and envy such an association of men of varied power and influence, because it is lofty, serene, impregnable, and, by the necessity of the case, exclusive." Do foolish people have a choice in the matter, so far as their essential foolishness can be effected?

I am already noting at this early stage that the book looks to be extremely quotable throughout. Then I wrote that the thinking people (illegible) who have (illegible) lost their taste for this sort of writing seem to think/live after a similar manner.

It's hard to get a cute girl picture to come up in a search for OWH Autocrat, etc, but this Boston duck boat driver will do.

I write my illegible notes in the book in pencil, in which I am hindered by the circumstance that my pencil sharpener does not evenly sharpen the pencils and makes them difficult to write with. I know that there are myriad easy ways to correct this situation, but nothing is really easy with me when it comes to trying to carry out some semblance of the life of the mind. I will never quite permanently solve my pencil problem, or my note taking problem, or my slow writing problem, or any other minor and irritating problem that besets me.

I forgot about when Holmes by way of establishing the mental climate out of which the book arose, introduced it as a world where most people listened to a hundred sermons a year.

Holmes likes a man of family. This hurts for me, since a lot of the more intelligent modern people seem to like that too, and the family that I came out of at least doesn't seem to excite anybody very much. He reverts to this theme several times in the course of the book, lamenting mésalliances in marriage between people whose backgrounds and breeding are not well matched. "No. my friends, I go (always, other things being equal) for the man who inherits family traditions and the cumulative humanities of at least four or five generations."

p. 43 "The woman who calc'lates is lost...Put not your trust in money, but put your money in trust." On matrimony. My poor wife trusted...So much so that she has said that if she were ever to remarry, it would only be for money.

p. 45 "Except in cases of necessity, which are rare, leave your friend to learn unpleasant truths from his enemies; they are ready enough to tell them."

p. 46 "Therefore conversation which is suggestive rather than argumentative, which lets out the most of each talker's results of thought, is commonly the pleasantest and the most profitable." Yes, but we must be convinced that our interlocutor is not an absolute dunce who is even capable of saying anything worth our listening to, which is rare in our time.

p. 54 "How many people live on the reputation of the reputation they might have made!" Not many anymore I wouldn't think. We've set ourselves with some dedication to snuffing out that kind of conceit.

p. 54 "When one of us who has been led by native vanity or senseless flattery to think himself or herself possessed of talent arrives at the full and final conclusion that he or she is really dull, it is one of the most tranquillizing and blessed convictions that can enter a mortal's mind." Yes and no. It may be liberating to an extent for the non-genius himself to realize his limitations, and it is certainly applauded by all the people who were annoyed by his ridiculous pretensions, but the people he has close relationships with who rely on him to some degree do not happily welcome the definitive proof that their fortunes are chained to a dullard with little prospect of improvement.

This is essentially the edition of the book I have, though instead of this teapot I have a red rectangle with a gold border and the initials O.W.H. imprinted on the field in gold letters.

p.58 There was a reference to news from India which was unclear to me, but a little research indicates that he must be referring to the Sepoy Rebellion of 1857. I am so conditioned to assume that insightful and adroit minds even in the past must have at some level been suspicious of the virtues of European colonialism (and certainly some were), that I thought that perhaps Holmes's references to unidentified women and children being outraged and babies being killed were oblique statements against British conduct, and that his referring to the Indians as the inferior race was ironic. But no, he was taking the pro-English position all the way.

Holmes ascribes powers to genuine (high) poetry and its relations/interactions with human souls that may contain some truth, but are largely foreign to the way almost everyone intelligent experiences life now.

He also makes an interesting mechanical comparison of the making of a poem to that of a fine violin, that time is necessary to dry out and fit together the many parts of which it is composed to produce the grand effect.

p. 146 I like the account of his morning rowing around Boston.

Holmes's own poems are interspersed throughout the book. They are for the most part not very good, difficult to read and scant on impressions and images. There are two poems that are moderately famous, or used to be, "The Chambered Nautilus", and "The Wonderful One-Hoss Shay", the latter a comic poem, that are markedly better than the rest.

p. 171 Holmes on people who smile stupidly for no good reason in social interactions: "...it is evident that the consciousness of some imbecility or other is at the bottom of this extraordinary expression. I don't think, however, that these persons are commonly fools. I have known a number, and all of them were intelligent. I think nothing conveys the idea of underbreeding more than this self-betraying smile." Underbreeding seems to me a useful concept that is not discussed nearly enough in our time.

He muses on how "there is no looking glass for the voice", such that people have no real sense of the sound of their own voices, and how pleasant it would be to be able to inhabit another form and be able to observe oneself speaking and moving. (Of course the technology to do this had not yet been developed in the 1850s).

There is a long and pleasant section about the trees of New England which is perhaps of greater interest if one happens to live here. Holmes notes many particular favorites and claims to "have as many tree-wives as Brigham Young has human ones." The loss of our elm trees was such a blow to New England's historical character. Holmes mentions them extensively, as does almost everyone who writes about the region prior to World War II.

Holmes sees the English and American varieties of elms as characteristic of the creative force of the respective countries. The English he describes as "compact, robust, holds its branches up, and carries its leaves for weeks longer than our own native tree", and the American as "tall, graceful, slender-sprayed, and drooping as if from languor." How this is related to the creative force of America especially I am hazy on.

pp. 261-2 "Qu'est-ce qu'il a fait? What has he done? That was Napoleon's test...Is a young man in the habit of writing verses? Then the presumption is that he is an inferior person. For...there are at least nine chances in ten that he writes poor verses." Common knowledge (sort of) now, but worth being reminded of and impressed on the young.

p. 279 "One's breeding shows itself nowhere more than in his religion."

If you have stuck out this post to this point, I thank you and consider you a true friend. I may not exactly be a tortured soul, but I do feel that I never quite made it as a fully accepted member of the educated classes, and I am lonely in my interests.

The Challenge

1. M. R. Carey--The Girl With All the Gifts.......................................................2,525

2. Haraki Murakami--1Q84................................................................................1,687

3. Tana French--The Secret Place.......................................................................1,663

4. Rachel Macy Stafford--Hands Free Mama.......................................................326

5. Jay Winik--1944: FDR & the Year That Changed History...............................301

6. Rachel Macy Stafford--Hands Free Life...........................................................222

7. D. H. Lawrence--Women In Love......................................................................147

8. John Whyte--Is This Normal? The Essential Guide to Middle Age & Beyond...35

9. Kathleen Ann Goonan--In War Times.................................................................28

10. Germany 1945: The Last Months of the War......................................................0

A small, but pretty strong field for our game, with seven 100+ scoring entrants and the top three seeds all north of 1,500!

1st Round

#7 Lawrence over #10 Germany

The Germany book appears to be a bilingual coffee table book of photographs that was published in Germany and has had no U.S. release. I read Women In Love, which does not appear on the IWE list and therefore qualifies for the Challenge, as the second book on my "A" list way back in December of 1994. It was not my favorite book at the time, though a few years later when I was about 28 I read The Rainbow, which preceded it and follows many of the same characters, and liked it very much, though I don't know if I would feel the same about that one if I read it now either.

#9 Goonan over #8 Whyte.

A close battle. The book about aging was not tempting enough to me to give it the edge here.

Final Eight

#9 Goonan over #1 Carey

Carey is a dreaded genre book. Also my library didn't have it.

#7 Lawrence over #2 Murakami

I was a little excited about the Murakami, which seems to have the status of a contemporary instant classic, but at 925 pages and with a tough matchup in its first game, it falls.

#6 Stafford over #3 French

French is a mega-genre writer, and her book is long. Plus Rachel Macy Stafford is a Generation X (b. 1972) supermom/superwife, Southern Christian variety, and what is not to like about that (if you're me)?

#4 Stafford over #5 Winik

While I acknowledge I have a crush on Rachel Macy Stafford, that is not the whole reason why she triumphs here over a major history. The 1,027 page length of the competitor's offering was what mainly killed it. Jay Winik has a demonstrated fondness for identifying years or even months that changed everything and writing books about them. Another title of his is April 1865: The Month That Saved America.

Final Four

#9 Goonan over #4 Stafford

#7 Lawrence over #6 Stafford

I was feeling guilty about passing over so much literature.

Championship

#9 Goonan over #7 Lawrence

Upset special. The Goonan is another science fiction book, which I have not have good experiences with so far (ed--apart from the Ray Bradbury book; I liked a lot of those stories), but I am willing to give it another try.

Monday, November 6, 2017

November Check In

"A" List: Jules Verne--Journey to the Center of the Earth.....................................28/195

"B" List: Oliver Wendell Holmes (Sr)--The Autocrat of the Breakfast Table........80/281

"C" List: Sol Stein--Stein on Writing....................................................................253/308

Three white guys, though one at least wrote in a foreign language, and Stein is still alive, albeit at age 91 he would appear to be superannuated as far as the current literary scene is concerned.

Jules Verne's books (I wrote about Around the World in Eighty Days in these pages earlier this year) have a decidedly fun quality about them, in addition to being intelligent/depicting intelligent people. I had not especially looked forward to reading any of his books though I had known some were coming for a long time, but I will from now on.

I like the Holmes too, perhaps because there is truly nothing like him being published today (not that there needs to be) and I suspect there is a lot in him that tells about the kind of country and region that we used to have here. He is however another high Victorian writer with an elaborate, somewhat overblown style whom I need to be well rested to concentrate on.

I remarked in an earlier post that I didn't think I was going to like the Stein book, but that turned out not to be the case. I actually found it encouraging, when I was expecting the opposite. Most of the advice I have kind of absorbed intuitively over the years, which is encouraging in itself. I think I have gotten out of it what I needed to get out of it. While it does not exactly repeat itself after the first eighty pages or so, I feel like I've got the idea, which is, briefly, that there are things any intelligent person with a little instinct for language can do will help your writing, and by extension your overall thinking. The book was published in 1995, so even though the blurb notes that Stein works at a couple of How-to-Write type webpages the internet and its particular flavor of writing as we know it had not exploded yet. One indication to me of the pre-internet mindset that I to some extent cane of age in is that Stein is strongly biased towards the form of fiction as more conducive to effective writing than that of non-fiction, which is not a sentiment I see much of anywhere in the present.

"B" List: Oliver Wendell Holmes (Sr)--The Autocrat of the Breakfast Table........80/281

"C" List: Sol Stein--Stein on Writing....................................................................253/308

Three white guys, though one at least wrote in a foreign language, and Stein is still alive, albeit at age 91 he would appear to be superannuated as far as the current literary scene is concerned.

Jules Verne's books (I wrote about Around the World in Eighty Days in these pages earlier this year) have a decidedly fun quality about them, in addition to being intelligent/depicting intelligent people. I had not especially looked forward to reading any of his books though I had known some were coming for a long time, but I will from now on.

I like the Holmes too, perhaps because there is truly nothing like him being published today (not that there needs to be) and I suspect there is a lot in him that tells about the kind of country and region that we used to have here. He is however another high Victorian writer with an elaborate, somewhat overblown style whom I need to be well rested to concentrate on.

I remarked in an earlier post that I didn't think I was going to like the Stein book, but that turned out not to be the case. I actually found it encouraging, when I was expecting the opposite. Most of the advice I have kind of absorbed intuitively over the years, which is encouraging in itself. I think I have gotten out of it what I needed to get out of it. While it does not exactly repeat itself after the first eighty pages or so, I feel like I've got the idea, which is, briefly, that there are things any intelligent person with a little instinct for language can do will help your writing, and by extension your overall thinking. The book was published in 1995, so even though the blurb notes that Stein works at a couple of How-to-Write type webpages the internet and its particular flavor of writing as we know it had not exploded yet. One indication to me of the pre-internet mindset that I to some extent cane of age in is that Stein is strongly biased towards the form of fiction as more conducive to effective writing than that of non-fiction, which is not a sentiment I see much of anywhere in the present.

Friday, October 27, 2017

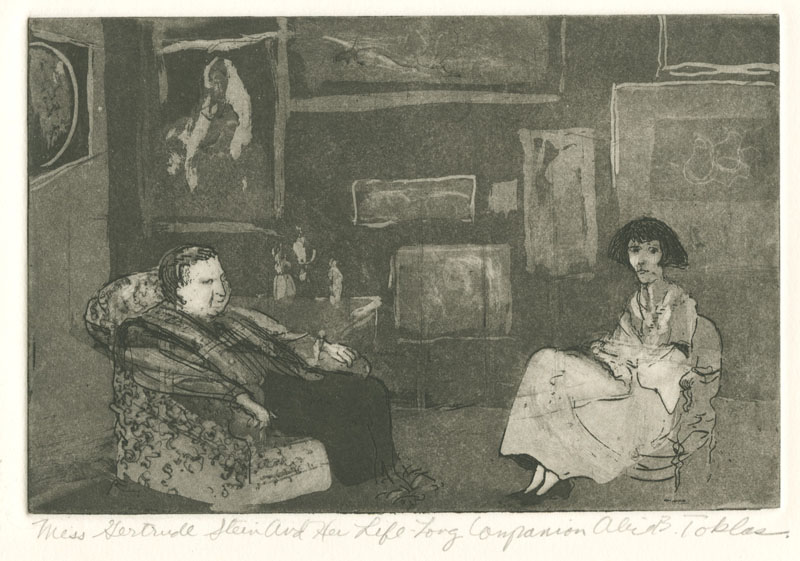

Gertrude Stein--The Autobiography of Alice B Toklas (1933)

Perhaps the most celebrated Americans in Paris book of them all, by the middle I was staying up late consuming baguettes and wine by the light of the stub of a candle babbling to my imaginary brilliant friends with even more fervency than usual. I enjoyed it very much, and was very into it. It is written as if it were a more or less true account of the lives of Gertrude Stein and Alice B Toklas. Evidently considerable portions of the book are not "true" or have been greatly embellished or whitewashed, though whether this is done to the point of being problematic I am not convinced. The point of literary and artistic production, which some people in our time seem to have forgotten, is to capture and fuse the all too fleeting highlights into an elevated sense of life, which is certainly accomplished here. Once I happened by accident to acquire an earlier draft of Boswell's Journey to the Hebrides that had been printed for the use of scholars and other curious parties. While it probably gave a more accurate sense of what the journey was really like on a day in, day out basis, it naturally lacked the high spirit and beauty of the published book that is what is of main interest to readers. Naturally a similar magic of time and place and character pervades this book as well.

I made a lot of notes on this book. Between the epigrammatic style and the characteristic anecdotes of many of the Notable and Great there is much material of the highest interest to me. So this will be a long posting.

As I moved through this I had occasion to do some internet searches about Gertrude Stein and other personages from the book, and I noted that a lot of the biographical sources pointedly identify her as a "Jewish-American writer". Once I saw that it struck me that of course she was, but I had had no conscience sense of it in reading the book because she never makes any reference to herself, or her parents or siblings or other relatives, as being Jewish or doing anything that might be considered explicitly characteristic of a Jewish identity. The only appearance of the word "Jew" in the book comes when Gertrude Stein remarks that a visitor to the house whose appearance she did not like "looks like a Jew", to which her interlocutor (Alfy Maurer, described as "an old habitué of the house") replies "he is worse than that," after which the matter is dropped.

The famous line(s) about Gertrude Stein conversing with the geniuses while Alice talked to the wives. There don't seem to have been any other women geniuses apart of course from Gertrude Stein.

p. 27 "Van Dongen (a painter) in these days was poor, he had a dutch wife who was a vegetarian and they lived on spinach. Van Dongen frequently escaped from the spinach to a joint in Montmartre

where the girls paid for his dinner and his drinks." I have to admit, I love the idea of this kind of life, absent the poverty. But if one has to be poor, Montmartre circa 1905 seems like the way to go.

p. 27 again, on a woman visitor to the house in these early years (Evelyn Thaw, "the heroine of the moment": "She was so blonde, so pale, so nothing, and Fernande (Picasso's live in companion at the time) would give a heavy sigh of admiration." I love that "so nothing" (!)

I had never heard the story about the infuriated public trying to scratch off the paint at one of Matisse's early exhibitions. That's insane.

p. 35 "In those days (we are still in the 1903-1907 chapter. I will note when we move on in time.) you were always going up stairs and down stairs."

I suppose I should say something about the techniques of a) writing another person's autobiography and/or b) writing your own autobiography in the guise of another person. It is done really well here and works beguilingly. As a class of reader who favors execution over novelty, I would love to read other books after the same pattern if they were done as well.

p. 49 My note--We can skip Picasso on Americans. We won't learn anything.

p. 50 Or maybe not. "There was a type of american art student, male, that used very much to afflict him, he used to say no it is not her who will make the future glory of America."

p. 52 "Baltimore is famous for the delicate sensibilities and conscientiousness of its inhabitants." I had never heard nor noticed this. One's instinct is to take it as dated information, but I am slowly coming around to the belief that if you dig deep enough there is no dated information.

p. 60 Still in the 1903-1907 chapter, but a good observation looking somewhat ahead, to the future death of the poet and bon vivant Guillaume Apollinaire: "It was the moment just after the war when many things had changed and people naturally fell apart." The breakup over time of this great prewar Montmartre-based circle of young artistic people with Picasso at the center is one of the more poignant partts of the book, though the twin (narrative) excitements of World War I followed by the emergence of a second group of youthful artists in the 20s mitigates some of the effect of contemplating the fleetingness of almost all really meaningful social intercourse.

p. 77 "Because Picasso is a spaniard and life is tragic and bitter and unhappy."

Now I am in the section "Gertrude Stein Before She Came to Paris". In the part where she talks about having been William James's favorite student in her college years I noted "real genius finds its like." Now I suspect this relationship may perhaps be one of the parts of the book that may been embellished, slightly or otherwise. A little embellishment of this sort does not really bother me if it improves the book.

That chapter was short, and I'm in the 1907-1914 chapter, which is probably the central one in the book.

p. 88 "Gertrude Stein insisted that no one could go to Assisi except on foot." I could still get to Assisi someday I suppose, though it isn't easy to see when that might happen, or what other options might pull me in a different direction if I ever do go anywhere again.

p. 91 "I always remember Picasso saying disgustedly apropos some germans who said they liked bull-fights, they would, he said angrily, they like bloodshed. To a spaniard it is not bloodshed, it is ritual." Ritual is deep and meaningful. People who don't have it are lacking in understanding.

p. 107 A very beautiful passage about the aftermath of a Montmartre party: "It was all very peaceful and about three o'clock in the morning we all went into the atelier where Salmon had been deposited and where we had left our hats and coats to get them to go home. There on the couch lay Salmon peacefully sleeping and surrounding him, half chewed, were a box of matches, a petit bleu and my yellow fantaisie. Imagine my feelings even at three o'clock in the morning. However, Salmon woke up very charming and very polite and we all went out into the street together. All of a sudden with a wild yell Salmon rushed down the hill." For some reason it was this particular memory that inspired me to write "I am dead inside" beside it in the margin.

Great photo of the celebrated duo at home.

p. 111 "I could perfectly understand Fernande's liking for Eve. As I said Fernande's great heroine was Evelyn Thaw, small and negative." I laughed.

p. 112 "And so Picasso left Montmartre never to return." Extremely poignant. The great spirit's time among this scene at least has passed.

p. 125 After the Italian futurists' big Paris show. "Jacques-Emile Blanche was terribly upset by it. We found him wandering tremblingly in the garden of the Tuileries and he said, it looks alright but is it. No it isn't, said Gertrude Stein. You do me good, said Jacques-Emile Blanche."

Now I've advanced to the chapter titled "The War." Whenever the opening scenes in the summer of 1914 appear in a novel written by someone with firsthand reminiscence of the time, whether in Russia, or France, or Austria, or anywhere else, it is always good, and always serves as a jolt to the book. The emotional upheaval of that initial embarking into war was obviously incredible, and one of the defining periods in the lives of everyone who lived through it.

p. 172 More name-dropping, as Picasso is hanging with the young Jean Cocteau! with whom he was heading to Italy. "One day Picasso came in and with him and leaning on his shoulder was a slim elegant youth." Oh yes. "Everybody was at the war, life in Montparnasse was not very gay...he too (Picasso) needed a change." Picasso and Cocteau would spend a lot of time together over the next 50 years, even appearing on celluloid together in Cocteau's 1960 film Orpheus Descending, which I was immediately recalled to when I came on this paragraph.

p. 187 (Driving through the north of France at the end of the war in the service of the American Fund For French Wounded) "Soon we came to the battle-fields and the lines of trenches for both sides. To anyone who did not see it as it was then it is impossible to imagine it. It was not terrifying it was strange." For what it's worth. Stein and Toklas, who lived until 1946 and 1967 respectively, also waited out World War II in France, though they moved out of Paris to the Auvergne-Rhone-Alpes region for the duration. Their friend Bernard Fay, who appears in the latter part of this book, became a high ranking official in the Vichy regime and seems to have arranged for the safety both of their persons and of Stein's art collection. In both written works and interviews that it doesn't seem to have been necessary to have made (she could have returned to America, at least before the occupation set in, for example) Stein made some incredibly naïve, tone-deaf, obtuse statements in praise of the collaborationist government. Considering all of this, her reputation doesn't seem to have taken that much of a hit, in that I think it's still considered O.K. to read about her and her scene in the happier times. Perhaps because she was a woman, and Jewish as well, her conduct during this period has been to some extent excused (on account of) her (being) comparatively powerless and not really understanding what was going on? Though given the resources she had access to, her American citizenship, and her fame in international high culture circles, I can't consider her to be that powerless. Maybe people feel that it doesn't matter, or that she really was a unique sort of genius and cannot be expected to experience moral crises and the like the same way that other people do. Picasso stayed in Paris during the occupation, which I had not realized, though he seems to have lain low and not exhibited any paintings during those years. Anecdotes on Wikipedia indicate that there was antagonism between him and the Germans. Of course everyone is in a different position relative to danger/power, etc in such times of turmoil, yet if we would be good we are expected to hold and behave with more or less the same attitude.

p. 189 "We once more returned to a changed Paris." After the war. I always in books and other art like the theme of how times change, the charm (? I can't read my note) if you are in it, and it is stimulating (and you are thinking?)

Now we are in the postwar (1919-1932) period. Hemingway has shown up. While Hemingway may have been an unbearable jerk later in life when he became famous and was surrounded by sycophants if he was hanging out with anybody at all, he seems to been a very attractive person as a young man, with a charming, life of the party type of energy. I found in this part that I missed him when he wasn't there, and he seems to have been generally popular with the older as well as the younger writers. I even thought he made a pretty good joke (p.200): "(Hemingway) said, when you matriculate at the University of Chicago you write down just what accent you will have and they give it to you when you graduate."

p. 212 Stein on the Hemingway era: "It became the period of being twenty-six. During the next two or three years all the young men were twenty-six years old. It was the right age apparently for that time and place."

p. 213 "Hemingway had then and has always (had) a very good instinct for finding apartments in strange but pleasing localities and good femmes de ménage and good food."

p. 238 "Gertrude Stein did not like hearing him (Paul Robeson, who was brought to the house) sing spirituals. They do not belong to you any more than anything else, so why claim them, she said. he did not answer...Gertrude Stein concluded that negroes were not suffering from persecution, they were suffering from nothingness. She always contends that the african is not primitive, he has a very ancient but a very narrow culture and there it remains. Consequently nothing does or can happen." I assume these statements were based on some thought process which is not however explored or elaborated on further. So I can't really understand what is meant by them.

p. 246 "(our finnish servant) finds it difficult to understand why we are not more modern (with regard to modern conveniences, electricity, radiators, etc). Gertrude Stein says that if you are way ahead with your head you naturally are old fashioned and regular in your daily life." Of course I am comparatively old fashioned and regular in my daily life, so this appealed to me.

p. 251 "Bowles told Gertrude Stein and it pleased her that Copland said threateningly to him when as usual in the winter he was neither delightful nor sensible, if you do not work now when you are twenty when you are thirty. nobody will love you." I have lived that. It is true. I try very hard to impress the fact upon my children.

I did love this book but seeing as it has taken me almost three weeks to do this report I also am missing the old warhorse books that make up this list and I am looking forward to getting back to it.

The Challenge

1. Edith Hamilton--Mythology................................................................647

2. Vampyr (movie-1932).........................................................................127

3. Harry Dolan--Very Bad Men...............................................................117

4. The Disappearance of Eleanor Rigby: Him (movie)............................91

5. Laurie R. King--Mary Russell's War....................................................84

6. Gay Talese--The Voyeurs' Motel..........................................................75

7. Stephanie Powell Watts--No One is Coming to Save Us.....................62

8. Robert Sussman--The Myth of Race.....................................................60

9. Luke Timothy Johnson--The New Testamant: A Very Short Introduc.17

10. T. A. Belshaw--Out of Control...........................................................12

11. Glass Animals--Zaba (record)..............................................................5

12. The Good Immigrant (ed. Nikesh Shukla)...........................................5

13. Merry A. Foresta--Artists Unframed....................................................3

14. Al Jolson--"California Here I Come" (record).....................................2

15. The World of Matisse 1869-1954.........................................................2

16. History of Gambling in America..........................................................1

1st Round

#1 Hamilton over #16 History of Gambling

Hamilton is a past champion of the challenge, and I enjoyed her book very much and found it useful. There is no rule banning past champions from competing again if they qualify (only books from the IWE list itself are ineligible), though in general I will probably prevent them from winning unless there is no desirable competition.

#15 Matisse over #2 Vampyr

#3 Dolan over #14 Jolson

#4 Rigby over #13 Foresta

One of those dreaded allotted upsets.

#5 King over #12 Good Immigrant

The Good Immigrant appears to be a British anthology. There aren't any copies of it in any of my libraries.

#11 Glass Animals over #6 Talese

I was actually excited to see Talese qualify for the Challenge. Unfortunately the Glass Animals had a designated upset to burn, and they burned it here.

#7 Watts over #10 Belshaw

#8 Sussman over #9 Johnson

2nd Round

#1 Hamilton over #15 Matisse

I was inclined to choose the Matisse here, but Hamilton comes in with all kinds of backup advantages to push through the early rounds.

#3 Dolan over #11 Glass Animals

#8 Sussman over #4 Rigby

#5 King over #7 Watts

This was a real battle, as these books are similar both in length and date of publication. King has a slight edge in all of the distinguishing categories however--1 year older, 22 more reviews, 71 pages shorter, etc.

Final Four

#1 Hamilton over #8 Sussman

If Hamilton had not already won the championship she would have easily carried off the title here. The Sussman looked interesting, though for some reason I thought it dated from the 50s, which would have made it more interesting. It actually was published in 2014, which causes me to be a little distrustful of it, as it would to be making an argument for a position that all respectable people, and most scientists as well, already seem to accept as fact.

#3 Dolan over #5 King

Dolan seems to be another murder book. I want to minimize those as much as possible since they quickly become repetitive, to me. The King, however, is a similar kind of book, and Dolan comes in with an upset card that he hasn't needed in the first two rounds against musical acts.

Championship

#3 Dolan over #1 Hamilton

I decided to see how the tournament played out and to have Hamilton drop the final unless the opponent was impossible. Dolan is not quite impossible and he is the survivor from the other side of the draw, so he gets an improbable victory.

The Winner. Born: Rome, N.Y. Colgate University. Age uncertain.

Friday, October 6, 2017

October Report

A List: Carroll, Alice in Wonderland.................................................................101/120

B List: Gertrude Stein, Autobiography of Alice B.Toklas..................................214/252

C List: Charlaine Harris, A Bone to Pick...........................................................131/262

Two books with "Alice" in the title is an interesting coincidence.

I know it hasn't been that long since I read about Alice for the IWE list and wrote about it here. However it had never come up on the A list before and sometimes it happens that certain books will have their turn come up on both lists fairly close in time--this occurred with The Age of Reason. The repetition does not bother me, in fact I find it helpful, since I don't actually have a very thorough familiarity with most of the central books in this line I have been following.

The Charlaine Harris book is one of a series of light, perhaps even mildly goofy, mysteries in which the sleuth is a librarian in a small town in Texas. There is some humor in it however, and a good pace, and I am enjoying it as a change from what I usually read. It was published in 1992, so it takes place in that pre-internet world of my young adulthood that I miss sometimes, though mostly I think because I don't travel or go to parties or fun social events anymore and I associate all of these fun things with that particular period of my life the end of which happened to coincide with the rise of ubiquitous technology and the increasingly sour national preoccupation with politics. But still, characters within the period of my own experience reading newspapers and looking up information in books, how can I resist?

Due to an extra block of words that did not properly belong to any particular book on the IWE list that I did not know what to do with, I decided to have a Bonus Mini-Challenge. Needless to say, one of the words used to generate results was "Stein".

1. Sol Stein--Stein on Writing....................................................................288

2. Sol Stein--How to Grow a Novel..............................................................61

3. Sol Stein--Reference Book for Writers.................................................... 10

For the record, I had #2 beat #3 and #1 beat #2 and I have already secured my copy of #1. It looks like it's going to make me feel bad about myself, since it is about serious professional level writing as practiced in the latter part of the 20th century, which must remind me in some way of everything that bothers me about my life. Well, tough, right. Take your medicine, boy.

B List: Gertrude Stein, Autobiography of Alice B.Toklas..................................214/252

C List: Charlaine Harris, A Bone to Pick...........................................................131/262

Two books with "Alice" in the title is an interesting coincidence.

I know it hasn't been that long since I read about Alice for the IWE list and wrote about it here. However it had never come up on the A list before and sometimes it happens that certain books will have their turn come up on both lists fairly close in time--this occurred with The Age of Reason. The repetition does not bother me, in fact I find it helpful, since I don't actually have a very thorough familiarity with most of the central books in this line I have been following.

The Charlaine Harris book is one of a series of light, perhaps even mildly goofy, mysteries in which the sleuth is a librarian in a small town in Texas. There is some humor in it however, and a good pace, and I am enjoying it as a change from what I usually read. It was published in 1992, so it takes place in that pre-internet world of my young adulthood that I miss sometimes, though mostly I think because I don't travel or go to parties or fun social events anymore and I associate all of these fun things with that particular period of my life the end of which happened to coincide with the rise of ubiquitous technology and the increasingly sour national preoccupation with politics. But still, characters within the period of my own experience reading newspapers and looking up information in books, how can I resist?

Due to an extra block of words that did not properly belong to any particular book on the IWE list that I did not know what to do with, I decided to have a Bonus Mini-Challenge. Needless to say, one of the words used to generate results was "Stein".

1. Sol Stein--Stein on Writing....................................................................288

2. Sol Stein--How to Grow a Novel..............................................................61

3. Sol Stein--Reference Book for Writers.................................................... 10

For the record, I had #2 beat #3 and #1 beat #2 and I have already secured my copy of #1. It looks like it's going to make me feel bad about myself, since it is about serious professional level writing as practiced in the latter part of the 20th century, which must remind me in some way of everything that bothers me about my life. Well, tough, right. Take your medicine, boy.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)