1. Los Angeles....................21

2. San Francisco..................5

3. Alameda..........................4

Monterey.........................4

5. Napa.................................2

Orange.............................2

San Bernardino................2

Santa Barbara..................2

Siskiyou...........................2

10. Contra Costa..................1

Kings................................1

Riverside..........................1

San Mateo........................1

Sonoma.............................1

Friday, March 13, 2015

Friday, March 6, 2015

Massachusetts

1. Middlesex....................20

2. Plymouth.....................10

3. Suffolk..........................7

4. Berkshire.......................3

Dukes............................3

Essex...………………..3

Hampden.......................3

8. Norfolk..........................2

Worcester......................2

10. Barnstaple....................1

2. Plymouth.....................10

3. Suffolk..........................7

4. Berkshire.......................3

Dukes............................3

Essex...………………..3

Hampden.......................3

8. Norfolk..........................2

Worcester......................2

10. Barnstaple....................1

Thursday, March 5, 2015

Robert Penn Warren--All the King's Men (1946)

This was a real book, of the old school. Winner of the Pulitzer Prize in 1946, the film version garnered the Oscar for best picture three years later, indicating that the story was seen in this country at least as one of the seminal works of the immediate postwar years. While there are a lot of things in and about this that I like I was really impressed with the beginning of the book, the first 100-150 pages or so. A lot of the books on this list, even when they are great literature, are books that are thought to hold some appeal for teenagers and lesser experienced readers. But the beginning of All the King's Men, I thought, was something even a real man might want to read. There were political machinations, graft, corruption, personal and sexual power and domination, the interaction of highly skilled professionals in various fields in various arenas where power, money and women are contended for. As the book went on however (my edition had 464 pages), it took the course of being less and less constantly centered on Willie Stark, the Huey Long stand-in who was by far the most compelling character in the book, and more on the narrator, Jack Burden, who though a little more hard-bitten than the usual examples of the type, is more of a traditional writerly character. The amount of space devoted to recollecting his long and not especially eventful romantic history with his adolescent girlfriend I think was especially unfortunate. I don't mind a little of that sort of thing, especially when it can serve to set a certain nostalgic atmosphere or mood, but this went way beyond that. A lot of modern readers find fault as well with the fairly lengthy Cass Mastern interlude, which is about the journal and romantic intrigues of one of Burden's Civil War era relatives, but I actually liked it. Flashbacks to the Civil War in southern novels, especially of this period, where the connection was still so palpable and personal, are usually pretty interesting.

The style of this book, which is highly descriptive and tends somewhat towards what would now be considered the wordy side, is very reminiscent of much masculine American literary writing in that era from around the mid-30s to the mid-60s, which is what I largely grew up on, but which I had not revisited in some years. I can still re-adapt to the style fairly easily, though it takes a couple of paragraphs for me to get back in the particular frame of mind needed to consume information in this form. I bought my copy of the book at a library sale in 1986, and have been lugging it around all this time, though I had not read it until now. The title page says it is a first edition, though it had already long been re-bound in orange library binding (which I kind of love anyway, by the way). The pages were yellowed and the book looked and felt like an antique to me even at that time, though the novel itself would only have been forty years old.

I am trying to convey what I most like about this book, for it has some very fine and powerful qualities. Since I am not being paid to produce polished essays, I am going to try to list some things that come to my mind bullet-point style:

1. The parts about driving on the old, (though at the time of the book's setting, they were new) lonely highways through the rural country and small towns and even the modest cities of Louisiana, which seems to have been still very much a quasi-feudal place in 1930 are very evocative.

2. There is often a sinister sense in books set in the 1930s in places outside the direct cultural authority of New York, London, Paris, Hollywood, and certain kinds of windblown midwestern American towns, and the character of Willie Stark especially gives this book a little bit of that, as if there is something bad in this environment that would crush any weaker person and that cannot be avoided or escaped from even by a stronger one. All of the indoor scenes feel to me to be taking place under dim institutional lighting, and the outdoor ones to carry some aura of geographical oppression in them.

3. I would not have wanted to live there, but I admit to having a fascination for certain aspects and relics of the Old South, particularly the era from 1910-1950 or so. When I am in that part of the world as a tourist I find I experience a certain sensation, almost like a thrill of danger, if I come upon old building or monument or even a tree that appears to have been overlooked in the process of modernization and preserved something of the old sinister but also in a way organic and vital aura that is usually lacking in the modern landscape. This is certainly not a romantic impulse, and a lot of these instances evoke a sense of horror or repulsion in its associations, but there is an attraction to it at the same time because of the darkness and reality that has been so well preserved in these kinds of books. There is some of that in here.

4. Another of my little tourism hobby horses is visiting state houses, which are usually old, attractive, uncrowded places, with a sense of drama and grandeur in understated ways. They often have old and somewhat grand bathrooms, for example, or staircases, or elevators, or light fixtures, or trees on the grounds, that have not been substantially modernized since the end of World War II. So it was enjoyable for me that much of the book took place in one of these buildings.

Most of the other things that come to mind are repititions of things I have already touched upon.

The New and Improved Bourgeois Surrender Challenge

I had written last time of changing the challenge to a tournament format. My initial plan had been to include every book (or movie, or record album) that came up in one giant tournament, but the magic words for All the King's Men produced around 70 competitors, most of which, as you can get a hint of in the list below, consisted of prestige books, which was a departure from the last Challenges under the old system. I decided to limit the field to the top sixteen contenders and see how that worked out:

1. Hunger Games: Catching Fire (movie).....................8,580

2. Secret Life of Walter Mitty (movie-2012)..................2,392

3. Carlos Ruiz Zafon--Shadow of the Wind....................1,633

4. Betty Smith--A Tree Grows in Brooklyn....................1,475

5. Salmon Fishing in the Yemen (movie)........................1,278

6. Donna Tartt--The Little Friend......................................924

7. David Foster Wallace--Infinite Jest...............................792

8. Night of the Living Dead (movie)..................................699

9. Nicole Krauss--The History of Love..............................599

10. Elizabeth Gaskell--North and South............................598

11. Jonathan Safran Foer--Everything is Illuminated........584

12. Charade (movie)..........................................................583

13. Don Delillo--Underworld.............................................397

14. Cecilia Ahern--P.S. I Love You.....................................396

15. Salman Rushdie--Midnight's Children.........................346

16. Virginia Woolf--To the Lighthouse..............................308

First, or Sweet Sixteen Round

#16 Virginia Woolf over #1 the Hunger Games.

Any good book will always have the preference over any movie in these tournaments, with the exception of one circumstance that I will reveal if the case ever arises.

#15 Salman Rushdie over #2 Walter Mitty

#3 Carlos Ruiz Zafon over #14 Cecilia Ahern

I don't know anything yet about Carlos Ruiz Zafon but the Ahern book appears to be a cookie-cutter genre/romance novel for the wine-drinking, shoe-shopping Sex in the City crowd, and I had marked it for automatic elimination against any 'real' book.

#4 Betty Smith over #13 Don Delillo

Besides being the higher seed, Betty Smith's book is shorter, older, and is more in the range of what I feel like reading at this time.

#12 Charade over #5 Salmon Fishing in the Yemen

Any movie with some claim to classic status that I have not seen will almost always have the preference over a more modern movie.

#11 Jonathan Safran Foer over #6 Donna Tartt

An extremely tight battle between two books that came out in the same year (2002), neither of which I am especially interested in reading. Foer wins because it's 300 pages shorter.

#10 Elizabeth Gaskell over #7 David Foster Wallace

Though I am not dying to read him either, I would give David Foster Wallace the win over markedly inferior competition. However Mrs Gaskell is good competition, she is older, and even at 521 pages her book is half the length of Wallace's.

#9 Nicole Krauss over #8 Night of the Living Dead.

Nicole Krauss has come up on the challenge twice now. I am mildly interested in her.

Elite 8

#3 Carlos Ruiz Zafon over #16 Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf loses here because I have already read To the Lighthouse. It is of course a great book, or at least I thought it was at the time that I read it, but I am curious enough about the highly seeded Zafon to be comfortable pressing forward with him.

#4 Betty Smith over #15 Salman Rushdie

Another grinder for Betty Smith over a powerful modern brand. However, her book was still shorter as well as older, and she was the higher seed as well. Those are deciding factors in this tournament.

#9 Nicole Krauss over #12 Charade

I have not read enough of the new young literary people to be be desirous of dismissing them out of hand against movies. Yet

#11 Jonathan Safran Foer over #10 Elizabeth Gaskell

Foer probably would have won here anyway due to his book's being 300 pages shorter. However a third criterion I am using is local library availability, and North and South does not seem to be in the collection of either of the libraries I can go to.

Final Four

#11 Jonathan Safron Foer Over #3 Carlos Ruiz Zafon

Availability and publication date were a wash here. Zafon got extra consideration because his book is a translation and we get so few books not written in English on the Challenge. Foer again wins by a nose because his book is 200 pages shorter. I don't mean to emphasize length so much, but I already have two literary lists I read off of, and this challenge is intended to be a means for me to find some fun reads that did not quite qualify for either of my lists and to keep in contact what is going on in contemporary life without excessive tension and anxiety.

#4 Betty Smith over #9 Nicole Krauss

Along with Foer, Betty Smith had the toughest draw in the tournament, Krauss's book is considerably shorter, but Smith wins on age and for being the higher seed.

The championship

#4 Betty Smith over #11 Jonahan Safron Foer.

Similar set-up to the Krauss win. A Tree Grows in Brooklyn is clearly the kind of book that I like, and I am looking forward to reading it.

The style of this book, which is highly descriptive and tends somewhat towards what would now be considered the wordy side, is very reminiscent of much masculine American literary writing in that era from around the mid-30s to the mid-60s, which is what I largely grew up on, but which I had not revisited in some years. I can still re-adapt to the style fairly easily, though it takes a couple of paragraphs for me to get back in the particular frame of mind needed to consume information in this form. I bought my copy of the book at a library sale in 1986, and have been lugging it around all this time, though I had not read it until now. The title page says it is a first edition, though it had already long been re-bound in orange library binding (which I kind of love anyway, by the way). The pages were yellowed and the book looked and felt like an antique to me even at that time, though the novel itself would only have been forty years old.

I am trying to convey what I most like about this book, for it has some very fine and powerful qualities. Since I am not being paid to produce polished essays, I am going to try to list some things that come to my mind bullet-point style:

1. The parts about driving on the old, (though at the time of the book's setting, they were new) lonely highways through the rural country and small towns and even the modest cities of Louisiana, which seems to have been still very much a quasi-feudal place in 1930 are very evocative.

2. There is often a sinister sense in books set in the 1930s in places outside the direct cultural authority of New York, London, Paris, Hollywood, and certain kinds of windblown midwestern American towns, and the character of Willie Stark especially gives this book a little bit of that, as if there is something bad in this environment that would crush any weaker person and that cannot be avoided or escaped from even by a stronger one. All of the indoor scenes feel to me to be taking place under dim institutional lighting, and the outdoor ones to carry some aura of geographical oppression in them.

3. I would not have wanted to live there, but I admit to having a fascination for certain aspects and relics of the Old South, particularly the era from 1910-1950 or so. When I am in that part of the world as a tourist I find I experience a certain sensation, almost like a thrill of danger, if I come upon old building or monument or even a tree that appears to have been overlooked in the process of modernization and preserved something of the old sinister but also in a way organic and vital aura that is usually lacking in the modern landscape. This is certainly not a romantic impulse, and a lot of these instances evoke a sense of horror or repulsion in its associations, but there is an attraction to it at the same time because of the darkness and reality that has been so well preserved in these kinds of books. There is some of that in here.

4. Another of my little tourism hobby horses is visiting state houses, which are usually old, attractive, uncrowded places, with a sense of drama and grandeur in understated ways. They often have old and somewhat grand bathrooms, for example, or staircases, or elevators, or light fixtures, or trees on the grounds, that have not been substantially modernized since the end of World War II. So it was enjoyable for me that much of the book took place in one of these buildings.

Most of the other things that come to mind are repititions of things I have already touched upon.

The New and Improved Bourgeois Surrender Challenge

I had written last time of changing the challenge to a tournament format. My initial plan had been to include every book (or movie, or record album) that came up in one giant tournament, but the magic words for All the King's Men produced around 70 competitors, most of which, as you can get a hint of in the list below, consisted of prestige books, which was a departure from the last Challenges under the old system. I decided to limit the field to the top sixteen contenders and see how that worked out:

1. Hunger Games: Catching Fire (movie).....................8,580

2. Secret Life of Walter Mitty (movie-2012)..................2,392

3. Carlos Ruiz Zafon--Shadow of the Wind....................1,633

4. Betty Smith--A Tree Grows in Brooklyn....................1,475

5. Salmon Fishing in the Yemen (movie)........................1,278

6. Donna Tartt--The Little Friend......................................924

7. David Foster Wallace--Infinite Jest...............................792

8. Night of the Living Dead (movie)..................................699

9. Nicole Krauss--The History of Love..............................599

10. Elizabeth Gaskell--North and South............................598

11. Jonathan Safran Foer--Everything is Illuminated........584

12. Charade (movie)..........................................................583

13. Don Delillo--Underworld.............................................397

14. Cecilia Ahern--P.S. I Love You.....................................396

15. Salman Rushdie--Midnight's Children.........................346

16. Virginia Woolf--To the Lighthouse..............................308

First, or Sweet Sixteen Round

#16 Virginia Woolf over #1 the Hunger Games.

Any good book will always have the preference over any movie in these tournaments, with the exception of one circumstance that I will reveal if the case ever arises.

#15 Salman Rushdie over #2 Walter Mitty

#3 Carlos Ruiz Zafon over #14 Cecilia Ahern

I don't know anything yet about Carlos Ruiz Zafon but the Ahern book appears to be a cookie-cutter genre/romance novel for the wine-drinking, shoe-shopping Sex in the City crowd, and I had marked it for automatic elimination against any 'real' book.

#4 Betty Smith over #13 Don Delillo

Besides being the higher seed, Betty Smith's book is shorter, older, and is more in the range of what I feel like reading at this time.

#12 Charade over #5 Salmon Fishing in the Yemen

Any movie with some claim to classic status that I have not seen will almost always have the preference over a more modern movie.

#11 Jonathan Safran Foer over #6 Donna Tartt

An extremely tight battle between two books that came out in the same year (2002), neither of which I am especially interested in reading. Foer wins because it's 300 pages shorter.

#10 Elizabeth Gaskell over #7 David Foster Wallace

Though I am not dying to read him either, I would give David Foster Wallace the win over markedly inferior competition. However Mrs Gaskell is good competition, she is older, and even at 521 pages her book is half the length of Wallace's.

#9 Nicole Krauss over #8 Night of the Living Dead.

Nicole Krauss has come up on the challenge twice now. I am mildly interested in her.

Elite 8

#3 Carlos Ruiz Zafon over #16 Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf loses here because I have already read To the Lighthouse. It is of course a great book, or at least I thought it was at the time that I read it, but I am curious enough about the highly seeded Zafon to be comfortable pressing forward with him.

#4 Betty Smith over #15 Salman Rushdie

Another grinder for Betty Smith over a powerful modern brand. However, her book was still shorter as well as older, and she was the higher seed as well. Those are deciding factors in this tournament.

#9 Nicole Krauss over #12 Charade

I have not read enough of the new young literary people to be be desirous of dismissing them out of hand against movies. Yet

#11 Jonathan Safran Foer over #10 Elizabeth Gaskell

Foer probably would have won here anyway due to his book's being 300 pages shorter. However a third criterion I am using is local library availability, and North and South does not seem to be in the collection of either of the libraries I can go to.

Final Four

#11 Jonathan Safron Foer Over #3 Carlos Ruiz Zafon

Availability and publication date were a wash here. Zafon got extra consideration because his book is a translation and we get so few books not written in English on the Challenge. Foer again wins by a nose because his book is 200 pages shorter. I don't mean to emphasize length so much, but I already have two literary lists I read off of, and this challenge is intended to be a means for me to find some fun reads that did not quite qualify for either of my lists and to keep in contact what is going on in contemporary life without excessive tension and anxiety.

#4 Betty Smith over #9 Nicole Krauss

Along with Foer, Betty Smith had the toughest draw in the tournament, Krauss's book is considerably shorter, but Smith wins on age and for being the higher seed.

The championship

#4 Betty Smith over #11 Jonahan Safron Foer.

Similar set-up to the Krauss win. A Tree Grows in Brooklyn is clearly the kind of book that I like, and I am looking forward to reading it.

Monday, February 2, 2015

Shakespeare--All's Well That Ends Well (1602 or 3)

First Shakespeare on the list. As we get deeper into it we are beginning to pick off more and more of these firsts, but there are still a few big areas out there that we have not gotten into. First Dickens, as well as other well-represented authors. First French, Russian, Spanish, modern Italian and Scandinavian books. First work in English of straight poetry (we have had a couple of dramas, namely this and Dryden, that have contained a considerable amount of verse so far). This is also the last of the series of readings, mainly plays and smaller novels, that were relatively short. The next five books on the list, at least--I try not to keep in mind more than five books ahead in doing this--are all on the longer side, at least 450 pages, with a couple even longer than that. I will read those at a somewhat more accelerated pace. I have been somewhat deliberate in reading these shorter ones because I wanted to feel that I had spent a little time with them. They all are become dear to me in some way and I don't want to just blow through them.

I have been finished with All's Well That Ends Well for about two weeks and have found that I have not had the energy in the evening, nor the time during the day, even to write up my little report. I don't want to fall behind on these.

I found with this, as I found with Virgil and Faulkner, the other two inner ring all time great authors we have come across on this list so far, that it was difficult to read late at night, which is by necessity the time when I do most of my reading (and writing), for more than a handful of pages before my concentration would break down and I would dose off to sleep. It is not that the books are completely beyond my reading ability when I am at close to full alertness and strength, as I have been reading these authors, and others in the same vein with a fair degree of familiarity with the style and language, at least, for twenty-five years. But old man fatigue is starting to hinder my ability to go back and take up the real Greats unless I am very fresh, well-rested and relaxed, which is a combination of circumstances I am finding myself hard-pressed to attain.

I haven't said anything about the actual play, which I am pretty sure I had never read before, as I would have recognized when I read Colley Cibber's Love's Last Shift a few years back the plot device of the neglected wife arranging for another woman to make an assignation with her wayward husband and taking the would be mistress's place in bed once darkness fell (which had been done long before Shakespeare as well). I enjoyed reading it, apart from my frustration on the occasions when I was unable to keep my eyes open. Everything with Shakespeare, especially after his first few plays, partakes of the character of the grand manner, and I am always alert to that sense, even if I am not alert enough to follow and make sense of the flow of the particular words on the page. I was surprised when I bothered to look at it at the relatively late date assigned to this play, as I tend to think of the comedies with Italian, or in this instance French-Italian, settings, as belonging to more or less the same period, and that the earlier part of Shakespeare's career before 1600, after which the tragedies became predominant. However I see that I am three or four years off in my calculating and that the 1600-1603 period was more comedy-heavy than I had realized, with Twelfth Night, Measure For Measure, The Merry Wives of Windsor, and other of the maturer ones coming out in these years.

I do not have a sense of what the best order to read Shakespeare would be if one is going to do it across a period of many years and at intervals among many other books. The IWE list does not have all of the plays, either--Pericles and Titus Andronicus at least did not make the cut--but it has most of them, and they will be coming up alphabetically. I think this was a good one to start with, as it is one of the lesser-known plays to the general reader, but it does partake of many of the best-loved qualities of the Shakespearean canon, the wit, the infectiousness and romance aroused by the language, the sense of being present both by the poetry and the setting of the story at the heart of all that defined and ever mattered about European civilization. The recovery, or acquisition, of some of these sensations is the whole raison d'etre for my undertaking this list at my time of life after all.

But I still haven't said anything about the play itself. No thoughts worth recording have come to me about it, nor have I been able to produce any on my own. High literature to someone like me is more a primer for how to try to live a little more nobly, with a little more purpose, with some mitigation of disgrace, than it is a fount for inquiring into serious ideas and human problems.

Main Square, Rousillon, France

The Challenge

I am going to attempt to revamp the Challenge between now and the next occasion for it, as it has died entirely in its current form. Here are the sorry results for the last exercise of this version of it:

1. The Countess Conspiracy--Courtney Milan.....................191

2. Confessions of Catherine de Medici--C. W. Gortner......127

3. Travels--William Bartram (1739-1823)..............................18

4. Framing the Early Middle Ages--Chris Wickham...............7

5. Romancing Lady Cecily--Ashley March..............................5

6. The Shaping of Southern Culture--Bertram Wyatt Brown...1

There was a movie challenge also:

1. The King's Speech.....................1,465

2. The Merchant of Venice (2004)...186

3. Quai des Orfevres..........................11

The Bartram book apparently is well-regarded. I am thinking in my future version of the game to go to a tournament format in which I choose in one-on-one matchups which book I think likely to appeal to me most through to a final.

I saw The King's Speech a few years back. I thought the subject, and the spirit in which it undertook that subject, to be strange. I wasn't in the mood to revisit it at this time.

I have been finished with All's Well That Ends Well for about two weeks and have found that I have not had the energy in the evening, nor the time during the day, even to write up my little report. I don't want to fall behind on these.

I found with this, as I found with Virgil and Faulkner, the other two inner ring all time great authors we have come across on this list so far, that it was difficult to read late at night, which is by necessity the time when I do most of my reading (and writing), for more than a handful of pages before my concentration would break down and I would dose off to sleep. It is not that the books are completely beyond my reading ability when I am at close to full alertness and strength, as I have been reading these authors, and others in the same vein with a fair degree of familiarity with the style and language, at least, for twenty-five years. But old man fatigue is starting to hinder my ability to go back and take up the real Greats unless I am very fresh, well-rested and relaxed, which is a combination of circumstances I am finding myself hard-pressed to attain.

I haven't said anything about the actual play, which I am pretty sure I had never read before, as I would have recognized when I read Colley Cibber's Love's Last Shift a few years back the plot device of the neglected wife arranging for another woman to make an assignation with her wayward husband and taking the would be mistress's place in bed once darkness fell (which had been done long before Shakespeare as well). I enjoyed reading it, apart from my frustration on the occasions when I was unable to keep my eyes open. Everything with Shakespeare, especially after his first few plays, partakes of the character of the grand manner, and I am always alert to that sense, even if I am not alert enough to follow and make sense of the flow of the particular words on the page. I was surprised when I bothered to look at it at the relatively late date assigned to this play, as I tend to think of the comedies with Italian, or in this instance French-Italian, settings, as belonging to more or less the same period, and that the earlier part of Shakespeare's career before 1600, after which the tragedies became predominant. However I see that I am three or four years off in my calculating and that the 1600-1603 period was more comedy-heavy than I had realized, with Twelfth Night, Measure For Measure, The Merry Wives of Windsor, and other of the maturer ones coming out in these years.

I do not have a sense of what the best order to read Shakespeare would be if one is going to do it across a period of many years and at intervals among many other books. The IWE list does not have all of the plays, either--Pericles and Titus Andronicus at least did not make the cut--but it has most of them, and they will be coming up alphabetically. I think this was a good one to start with, as it is one of the lesser-known plays to the general reader, but it does partake of many of the best-loved qualities of the Shakespearean canon, the wit, the infectiousness and romance aroused by the language, the sense of being present both by the poetry and the setting of the story at the heart of all that defined and ever mattered about European civilization. The recovery, or acquisition, of some of these sensations is the whole raison d'etre for my undertaking this list at my time of life after all.

But I still haven't said anything about the play itself. No thoughts worth recording have come to me about it, nor have I been able to produce any on my own. High literature to someone like me is more a primer for how to try to live a little more nobly, with a little more purpose, with some mitigation of disgrace, than it is a fount for inquiring into serious ideas and human problems.

Main Square, Rousillon, France

The Challenge

I am going to attempt to revamp the Challenge between now and the next occasion for it, as it has died entirely in its current form. Here are the sorry results for the last exercise of this version of it:

1. The Countess Conspiracy--Courtney Milan.....................191

2. Confessions of Catherine de Medici--C. W. Gortner......127

3. Travels--William Bartram (1739-1823)..............................18

4. Framing the Early Middle Ages--Chris Wickham...............7

5. Romancing Lady Cecily--Ashley March..............................5

6. The Shaping of Southern Culture--Bertram Wyatt Brown...1

There was a movie challenge also:

1. The King's Speech.....................1,465

2. The Merchant of Venice (2004)...186

3. Quai des Orfevres..........................11

The Bartram book apparently is well-regarded. I am thinking in my future version of the game to go to a tournament format in which I choose in one-on-one matchups which book I think likely to appeal to me most through to a final.

I saw The King's Speech a few years back. I thought the subject, and the spirit in which it undertook that subject, to be strange. I wasn't in the mood to revisit it at this time.

Wednesday, January 28, 2015

One More Note on All Quiet on the Western Front

Reading in any war book about the food people had to survive on--thin broth with the barest trace of gristle in it, rotting turnips, ditch water, week old bread crusts--arouses in me fantasies of modern day food snobs being subjected to, if not quite this severe a regime, at least wartime era civilian rationing for some extended period of time. The rationed food would not even have to be bad, maybe--just limited in supply, and, most importantly, everybody would have to eat, qualitatively speaking, more or less the same thing. Yes, I am expressing a wormlike desire to see people humbled for at least sensing some aspect of personal superiority in themselves and daring to express it. But I can't endure the archness, pomposity, and judgments upon others' tastes and, by implication, characters and mental capacities, on the subjects of eating and drinking without wanting to see that person driven from whatever level of society he imagines himself to exist on and forced to survive on whatever delicacies he mocked other people for partaking of--forever.

Contrary to what the paragraph above suggests, I have experienced happiness from what I perceived to be superior food and drink in the course of my life, though I am sure I have never felt in doing so the sense of triumph over lesser people or even my former or accustomed lesser self that seems to animate much of the study and experience of heightened eating among the initiated. Most of my happiest memories have had nothing to do with my being superior or in any way more savvy than other people, but were the product of stumbling upon a food culture being so advanced in some area that even the vulgar and socially undeserving could not fail to be exposed to certain delicacies of high quality, because all comparable inferior products had been marginalized or entirely absented from the market--this characterizes things like the beer in the Czech Republic and Germany, bread in France and Italy, coffee and the cafe scene in Austria and elsewhere in the former domains of the Hapsburg empire--you get the idea. The mundaneness, and often fadedness of most of these settings, whose staff and patrons rarely betrayed any consciousness of being inherently above any rivals real or imagined on gustatory grounds, calmed me and put me into the proper mindframe to sense the superior quality of its mundane offerings.

It is clear to me that a major source of the disdain among more cosmopolitan Americans for their less educationally accomplished compatriots is the failure, apart from a few isolated exceptions like the Cajuns in Louisana or maybe some of the more renowned centers of barbeque in the south, of these lower orders to develop, or sustain, a substantial cuisine, especially one in resistance to that pressed upon them by corporate interests. It is hard to overstate the degree of contempt and physical revulsion with which a substantial and socially influential (among the nominally and in some instances certifiedly intelligent) segment of the population has come to regard the ingestion of certain food products, and by extension anyone known or suspected to ingest them on a consistent basis.

I have a rant about the growth of beer snobbery too. First of all, I have drunk a lot of beer in my life. I have had it pretty much every day, and usually a decent amount, for the last twenty-five years. As people know, I lived in the Czech Republic for a couple of years, a country where deciding what beer to drink with breakfast is an important, though not socially deterministic, daily consideration. If one of these little i-phone tapping snots ever tries to tell me to my face to 'get a palate' I may rip the flesh clean off of his skull. Given that beer has traditionally, in the countries where it is most central in the national life, evolved to be consumed in fairly large quantities over a period lasting multiple hours, the most important indicator of quality, and one that correlates strongly with taste, or at least enjoyment of imbibing, because most of my favorite beers do not have a flavor that I identify other than that they taste to me more like beer, that is to say that they give me a perfect sensation of drinking liquid bread and that the pleasure in this will never diminish or grow old, than other varieties do, is in their consistency...

All right, I could go on in that vein for a while, but I will call it a night for (there are some good beer garden scenes and ruminations in AQOTWF by the way...

February 1, 2019--I was really wound up the day I wrote this. I have not gotten this angry for a while. Even at food snobs.

Contrary to what the paragraph above suggests, I have experienced happiness from what I perceived to be superior food and drink in the course of my life, though I am sure I have never felt in doing so the sense of triumph over lesser people or even my former or accustomed lesser self that seems to animate much of the study and experience of heightened eating among the initiated. Most of my happiest memories have had nothing to do with my being superior or in any way more savvy than other people, but were the product of stumbling upon a food culture being so advanced in some area that even the vulgar and socially undeserving could not fail to be exposed to certain delicacies of high quality, because all comparable inferior products had been marginalized or entirely absented from the market--this characterizes things like the beer in the Czech Republic and Germany, bread in France and Italy, coffee and the cafe scene in Austria and elsewhere in the former domains of the Hapsburg empire--you get the idea. The mundaneness, and often fadedness of most of these settings, whose staff and patrons rarely betrayed any consciousness of being inherently above any rivals real or imagined on gustatory grounds, calmed me and put me into the proper mindframe to sense the superior quality of its mundane offerings.

It is clear to me that a major source of the disdain among more cosmopolitan Americans for their less educationally accomplished compatriots is the failure, apart from a few isolated exceptions like the Cajuns in Louisana or maybe some of the more renowned centers of barbeque in the south, of these lower orders to develop, or sustain, a substantial cuisine, especially one in resistance to that pressed upon them by corporate interests. It is hard to overstate the degree of contempt and physical revulsion with which a substantial and socially influential (among the nominally and in some instances certifiedly intelligent) segment of the population has come to regard the ingestion of certain food products, and by extension anyone known or suspected to ingest them on a consistent basis.

I have a rant about the growth of beer snobbery too. First of all, I have drunk a lot of beer in my life. I have had it pretty much every day, and usually a decent amount, for the last twenty-five years. As people know, I lived in the Czech Republic for a couple of years, a country where deciding what beer to drink with breakfast is an important, though not socially deterministic, daily consideration. If one of these little i-phone tapping snots ever tries to tell me to my face to 'get a palate' I may rip the flesh clean off of his skull. Given that beer has traditionally, in the countries where it is most central in the national life, evolved to be consumed in fairly large quantities over a period lasting multiple hours, the most important indicator of quality, and one that correlates strongly with taste, or at least enjoyment of imbibing, because most of my favorite beers do not have a flavor that I identify other than that they taste to me more like beer, that is to say that they give me a perfect sensation of drinking liquid bread and that the pleasure in this will never diminish or grow old, than other varieties do, is in their consistency...

All right, I could go on in that vein for a while, but I will call it a night for (there are some good beer garden scenes and ruminations in AQOTWF by the way...

February 1, 2019--I was really wound up the day I wrote this. I have not gotten this angry for a while. Even at food snobs.

Tuesday, January 13, 2015

Author List Volume VII

Arthur Koestler (1905-1983) Darkness at Noon (1941) Born: Sziv Street 16, Budapest, Hungary. Buried: Cremated, location of ashes unknown. College: Vienna Polytechnic.

Edward Noyes Westcott (1846-1898) David Harum (1898) Born: Syracuse, Onodaga, New York. Buried: Oakwood Cemetery, Syracuse, Onondaga, New York.

Nikolai Gogol (1809-1852) Dead Souls (1842), The Overcoat (1842) Born: Gogol Memorial Museum, Velyki Sorochyntsi, Ukraine. Buried: Novodevichy Cemetery, Moscow, Russia. Gogol Museum, 7 Nikitsky Boulevard, Moscow, Russia. Gogol Museum, Sistina Street, Rome, Lazio, Italy.

Brutus (85-42 B.C.) Born: Rome, Lazio, Italy.

Cassius (c. 85-42 B.C.) Born: unknown. Buried: Thasos, East Macedonia & Thrace, Greece. Cassius Roma Restaurant, Orizaba 76, Mexico City, Mexico.

Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375) The Decameron (1353-1358). Born: Via Boccaccio, Certaldo, Tuscany, Italy. Buried: Church of Saints Jacopo and Phillippo, Certaldo, Tuscany, Italy.

Madame de Stael (Germaine) (1766-1817) Delphine (1802) Born: 28 Rue Michel-le-Comte, 3eme, Paris, France. Buried: Chateau de Coppet, Coppet, Switzerland.

Napoleon (1769-1821) Born: Casa Buonaparte, Rue St Charles, Ajaccio, Corsica, France. Buried: Les Invalides, 7eme, Paris, France. Napoleon Museum, Monte Carlo, Monaco (Better go soon. It looks like the collection is being sold off next month). College: Ecole Militaire.

Francois Mauriac (1885-1970) Desert of Love (1925) Born: 86 Rue du Pas-St-Georges, Bordeaux, Aquitaine, France. Buried: Cimitiere de Vemars, Vemars, Val d'Oise, Ile-de France, France. Musee Francois Mauriac, Rue Leon Bouchard, Vemars, Val d'Oise, Ile-de-France, France. Centre Francois Mauriac, 17 Route de Malagar, Saint-Maixant, Gironde, France. College: Bordeaux.

George Meredith (1828-1909) The Ordeal of Richard Feverel (1859), The Egoist (1879), Diana of the Crossways (1885) Born: 73 High Street, Portsmouth, Hampshire, England. Buried: Dorking Cemetery, Dorking, Surrey, England.

Caroline Norton (1808-1877) Born: London, England. Buried: Lecropt Church, Lecropt, Stirlingshire, Scotland. Portrait by Heyter, Chatsworth House, Bakewell, Derbyshire, England.

Lord Melbourne (William Lamb) (1779-1848) Born: Melbourne Hall, Church Square, Melbourne, Derbyshire, England. Buried: St Etheldreda Church, Hatfield, Hertfordshire, England. Lord Melbourne Hotel, 63 Melbourne Street, North Adelaide, Australia. College: Trinity (Cambridge).

George Chapple Norton (1800-1875) Born: Kettlethorpe Hall, Wakefield, Yorkshire, England. Buried: Unknown. College: Edinburgh.

Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) The Divine Comedy (1300-21) Born: Casa di Dante, Via S. Margherita 1, Florence, Tuscany, Italy (*****3-3-97*****). Buried: Tomba di Dante, Ravenna, Emilio-Romagna, Italy.

Beatrice Portinari (1266-1290) Born: Palazzo Portinari Salviati, Via del Corso 6, Florence, Tuscany, Italy. Buried: Chiesa di Santa Margherita di Cerchi, Florence, Tuscany, Italy.

Percy Shelley (1792-1822) Born: Field Place, Warnham, Sussex, England. Buried: Protestant Cemetery, Rome, Lazio, Italy (*****3-1-01*****) Heart, Churchyard, St Peter's Church, Bournemouth, Hampshire, England. Keats-Shelley House, 26 Piazza di Spagna, Rome, Lazio, Italy (*****3-1-01*****) College: University (Oxford).

Robert Louis Stevenson (1850-1894) Treasure Island (1883), Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), Kidnapped (1886) Born: 8 Howard Place, Edinburgh, Lothian, Scotland. Buried: Mount Vaea, Upolu, Samoa. Robert Louis Stevenson Museum, 1490 Library Lane, St Helena, Napa, California. Robert Louis Stevenson Museum, Vailima, Samoa. Robert Louis Stevenson Memorial Cottage and Museum, 11 Stevenson Lane, Saranac Lake, Essex, New York. Stevenson House Adobe & Garden, 530 Houston Street, Monterey, Monterey, California. Robert Louis Stevenson State Park, Calistoga, Napa, California. Statue, Colinton Parish Church, Dell Road, Colinton, Edinburgh, Lothian, Scotland. Edinburgh Writers' Museum, Lady Stair's Close, Edinburgh, Lothian, Scotland. College: Edinburgh.

Henrik Ibsen (1828-1906) A Doll's House (1879), Ghosts (1881), Hedda Gabler (1890) Born: Henrik Ibsen Museum, Venstophogda 74, Skien, Norway. (*****6-28-00*****) Buried: Var Freslurs Gravlund, Oslo, Norway. (*****6-26-00*****) Ibsenmuseet, Henrik Ibsens Gate 26, Oslo, Norway. (*****6-26-00*****) Ibsen-Museet, Grimstad, Norway (*****6-30-00*****).

Erechtheion, Athens, Attica, Greece.

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (1547-1616) Don Quixote (1605, 1615) Born: Casa Natale de Cervantes, C/Mayor 48, Alcala de Henares, Madrid aut. com., Spain. Buried: Convento de los Trinitarios, Madrid, Spain. Hostal Miguel de Cervantes, Calle la Imogen 12, Alcala de Henares, Madrid aut. com., Spain. Museo Casa de Cervantes. Calle Rastro, Valladolid, Castile and Leon, Spain. Statue, Plaza de Espana, Madrid, Spain. Instituto Miguel de Cervantes, Guanajuato, Mexico.

Peter Anthony Motteux (1663-1718) Born: Rouen, Upper Normandy, France. Buried: St Andrew Undershaft Churchyard, City, London, England.

James M. Cain (1892-1977) Double Indemnity (1943) Born: Paca-Carroll House, St John's College, Annapolis, Maryland. Buried: Body donated to medical science. College: Washington (Maryland).

Bram Stoker (1847-1912) Dracula (1897) Born: 15 Marino Crescent, Clontarf, Dublin, Ireland. Buried: Golders Green Crematorium, Golders Green, London, England. Castle Dracula, Clontarf, Dublin, Ireland. Bram Stoker Dracula Experience, 9 Marine Parade, Whitby, Yorkshire, England. College: Trinity (Dublin).

Henry Adams (1838-1918) The Education of Henry Adams (1907) Born: Mt Vernon Place, Boston, Suffolk, Massachusetts. Buried: Rock Creek Cemetery, Washington, D.C. Harvard Yard, Cambridge, Middlesex, Massachusetts. Mont-St-Michel, Lower Normandy, France. Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, Centre, France. College: Harvard.

Charles Francis Adams (1807-1886) Born: SE Corner Boylston & Tremont Streets, Boston, Suffolk, Massachusetts. Buried: Mt Wollaston Cemetery, Quincy, Norfolk, Massachusetts. College: Harvard

Edward Noyes Westcott (1846-1898) David Harum (1898) Born: Syracuse, Onodaga, New York. Buried: Oakwood Cemetery, Syracuse, Onondaga, New York.

Nikolai Gogol (1809-1852) Dead Souls (1842), The Overcoat (1842) Born: Gogol Memorial Museum, Velyki Sorochyntsi, Ukraine. Buried: Novodevichy Cemetery, Moscow, Russia. Gogol Museum, 7 Nikitsky Boulevard, Moscow, Russia. Gogol Museum, Sistina Street, Rome, Lazio, Italy.

Brutus (85-42 B.C.) Born: Rome, Lazio, Italy.

Cassius (c. 85-42 B.C.) Born: unknown. Buried: Thasos, East Macedonia & Thrace, Greece. Cassius Roma Restaurant, Orizaba 76, Mexico City, Mexico.

Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375) The Decameron (1353-1358). Born: Via Boccaccio, Certaldo, Tuscany, Italy. Buried: Church of Saints Jacopo and Phillippo, Certaldo, Tuscany, Italy.

Madame de Stael (Germaine) (1766-1817) Delphine (1802) Born: 28 Rue Michel-le-Comte, 3eme, Paris, France. Buried: Chateau de Coppet, Coppet, Switzerland.

Napoleon (1769-1821) Born: Casa Buonaparte, Rue St Charles, Ajaccio, Corsica, France. Buried: Les Invalides, 7eme, Paris, France. Napoleon Museum, Monte Carlo, Monaco (Better go soon. It looks like the collection is being sold off next month). College: Ecole Militaire.

Francois Mauriac (1885-1970) Desert of Love (1925) Born: 86 Rue du Pas-St-Georges, Bordeaux, Aquitaine, France. Buried: Cimitiere de Vemars, Vemars, Val d'Oise, Ile-de France, France. Musee Francois Mauriac, Rue Leon Bouchard, Vemars, Val d'Oise, Ile-de-France, France. Centre Francois Mauriac, 17 Route de Malagar, Saint-Maixant, Gironde, France. College: Bordeaux.

George Meredith (1828-1909) The Ordeal of Richard Feverel (1859), The Egoist (1879), Diana of the Crossways (1885) Born: 73 High Street, Portsmouth, Hampshire, England. Buried: Dorking Cemetery, Dorking, Surrey, England.

Caroline Norton (1808-1877) Born: London, England. Buried: Lecropt Church, Lecropt, Stirlingshire, Scotland. Portrait by Heyter, Chatsworth House, Bakewell, Derbyshire, England.

Lord Melbourne (William Lamb) (1779-1848) Born: Melbourne Hall, Church Square, Melbourne, Derbyshire, England. Buried: St Etheldreda Church, Hatfield, Hertfordshire, England. Lord Melbourne Hotel, 63 Melbourne Street, North Adelaide, Australia. College: Trinity (Cambridge).

George Chapple Norton (1800-1875) Born: Kettlethorpe Hall, Wakefield, Yorkshire, England. Buried: Unknown. College: Edinburgh.

Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) The Divine Comedy (1300-21) Born: Casa di Dante, Via S. Margherita 1, Florence, Tuscany, Italy (*****3-3-97*****). Buried: Tomba di Dante, Ravenna, Emilio-Romagna, Italy.

Beatrice Portinari (1266-1290) Born: Palazzo Portinari Salviati, Via del Corso 6, Florence, Tuscany, Italy. Buried: Chiesa di Santa Margherita di Cerchi, Florence, Tuscany, Italy.

Percy Shelley (1792-1822) Born: Field Place, Warnham, Sussex, England. Buried: Protestant Cemetery, Rome, Lazio, Italy (*****3-1-01*****) Heart, Churchyard, St Peter's Church, Bournemouth, Hampshire, England. Keats-Shelley House, 26 Piazza di Spagna, Rome, Lazio, Italy (*****3-1-01*****) College: University (Oxford).

Robert Louis Stevenson (1850-1894) Treasure Island (1883), Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), Kidnapped (1886) Born: 8 Howard Place, Edinburgh, Lothian, Scotland. Buried: Mount Vaea, Upolu, Samoa. Robert Louis Stevenson Museum, 1490 Library Lane, St Helena, Napa, California. Robert Louis Stevenson Museum, Vailima, Samoa. Robert Louis Stevenson Memorial Cottage and Museum, 11 Stevenson Lane, Saranac Lake, Essex, New York. Stevenson House Adobe & Garden, 530 Houston Street, Monterey, Monterey, California. Robert Louis Stevenson State Park, Calistoga, Napa, California. Statue, Colinton Parish Church, Dell Road, Colinton, Edinburgh, Lothian, Scotland. Edinburgh Writers' Museum, Lady Stair's Close, Edinburgh, Lothian, Scotland. College: Edinburgh.

Henrik Ibsen (1828-1906) A Doll's House (1879), Ghosts (1881), Hedda Gabler (1890) Born: Henrik Ibsen Museum, Venstophogda 74, Skien, Norway. (*****6-28-00*****) Buried: Var Freslurs Gravlund, Oslo, Norway. (*****6-26-00*****) Ibsenmuseet, Henrik Ibsens Gate 26, Oslo, Norway. (*****6-26-00*****) Ibsen-Museet, Grimstad, Norway (*****6-30-00*****).

Erechtheion, Athens, Attica, Greece.

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (1547-1616) Don Quixote (1605, 1615) Born: Casa Natale de Cervantes, C/Mayor 48, Alcala de Henares, Madrid aut. com., Spain. Buried: Convento de los Trinitarios, Madrid, Spain. Hostal Miguel de Cervantes, Calle la Imogen 12, Alcala de Henares, Madrid aut. com., Spain. Museo Casa de Cervantes. Calle Rastro, Valladolid, Castile and Leon, Spain. Statue, Plaza de Espana, Madrid, Spain. Instituto Miguel de Cervantes, Guanajuato, Mexico.

Peter Anthony Motteux (1663-1718) Born: Rouen, Upper Normandy, France. Buried: St Andrew Undershaft Churchyard, City, London, England.

James M. Cain (1892-1977) Double Indemnity (1943) Born: Paca-Carroll House, St John's College, Annapolis, Maryland. Buried: Body donated to medical science. College: Washington (Maryland).

Bram Stoker (1847-1912) Dracula (1897) Born: 15 Marino Crescent, Clontarf, Dublin, Ireland. Buried: Golders Green Crematorium, Golders Green, London, England. Castle Dracula, Clontarf, Dublin, Ireland. Bram Stoker Dracula Experience, 9 Marine Parade, Whitby, Yorkshire, England. College: Trinity (Dublin).

Henry Adams (1838-1918) The Education of Henry Adams (1907) Born: Mt Vernon Place, Boston, Suffolk, Massachusetts. Buried: Rock Creek Cemetery, Washington, D.C. Harvard Yard, Cambridge, Middlesex, Massachusetts. Mont-St-Michel, Lower Normandy, France. Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, Centre, France. College: Harvard.

Charles Francis Adams (1807-1886) Born: SE Corner Boylston & Tremont Streets, Boston, Suffolk, Massachusetts. Buried: Mt Wollaston Cemetery, Quincy, Norfolk, Massachusetts. College: Harvard

Monday, January 12, 2015

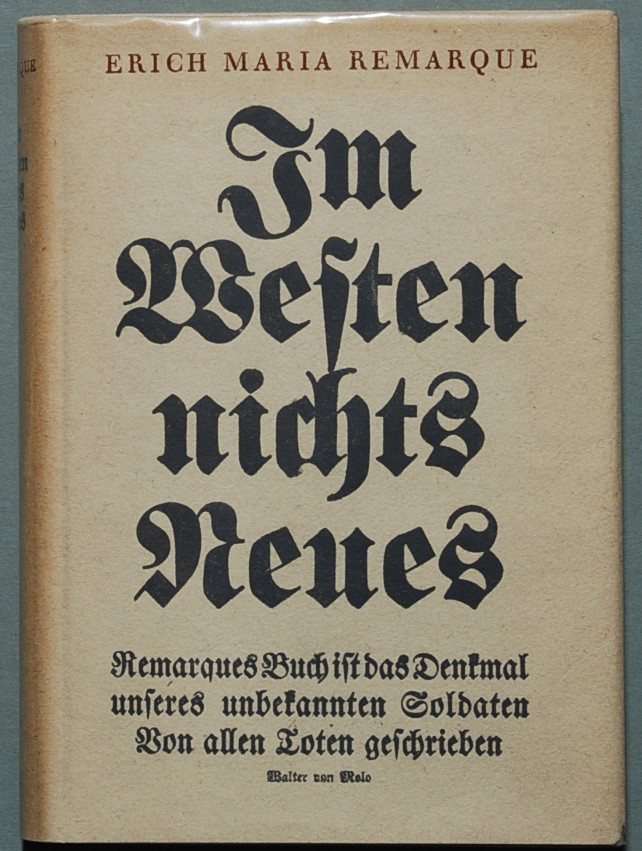

Erich Maria Remarque--All Quiet on the Western Front (1929)

One would think that there must have been many efforts made at writing books taking up the same general theme as this one in the years following the first world war. But out of all of those efforts, this is one of the handful that made the greatest impact on the popular imagination of the Western nations in its time, and has come down to our own day, as far as I can make out, as the novel most closely associated with the 'experience', as it were, of that watershed catastrophe of modern history, particularly with regard to the trench warfare of the western front. I had never read it until now, though I had always been interested in doing so, and I was not disappointed. While there is some nitpicking on literary grounds that could be made, it is a good book, moving, it has a soul to it. It is to my mind short (299 pages of standard print--under 180 or so I barely consider to be a novel), and is written in the to me agreeable modern style that arose between the wars, which was unexpected, even though the IWE introduction itself noted that it had 'the clipped sentences, brief paragraphs, and unadorned descriptive language that have proved so effective in the novels of James M. Cain(!).' This makes the book a rather quick read; I actually would not have minded a little more incident and character development, though I appreciate that it is really difficult to produce a book that is successful and resonant to any degree, and that the tone and briefly recounted characters and incidents--which does give them, probably intentionally, a rather ghostly effect in the reader's imagination--are what makes this particular story work.

I did not read this in high school, but I think in the past it was often read in high school, and it does seem like it would still be a good book for the earlier high school years, 9th or 10th grade, for particular kinds of students anyway, who, however, make up an ever-dwindling percentage of the school-age population and whom the education authorities are ever obsessed about not being perceived to favor in the organization of school curriculums (curricula?). But I think in certain instances it could be a valuable part of a literary education.

Fifteen or twenty years ago when I was recently out of school and more of a closer reader than I am now, I don't know that I would have thought as much of this book, or been as moved by it as I am again now (I probably would have felt a fondness for it in high school). This even though its literary flaws, with which one would think I of all people would have been sympathetic, are primarily the result of a young man (Remarque was 32 when the book was published) who has lived through an apocalypse and is unloading his memories of that experience with at times a mild excess of emotion and rage that is not focused with perfect precision. It is probably not full of deep intellectual insights--I doubt the Straussians would have much interest in it--but the emotional despair of this shattered generation has always resonated with me, and this was as affecting as anything else I have read about this war in that regard.

I will only include one quote, which I think conveys the spirit of the book pretty well. It is during the part when the narrator, Baumer, is home on leave and has to pay a visit to the mother of one of his old schoolmates and fellow soldiers who has died. Predictably, the mother carries on hysterically, to the irritation of Baumer:

"I console her, but she strikes me as rather stupid all the same. Why doesn't she stop worrying? Kemmerich will stay dead whether she knows about it or not. When a man has seen so many dead he cannot understand any longer why there should be so much anguish over a single individual."

The descriptions of death, and especially of corpses, in this are more than usually striking. Shell blasts and shrapnel blew bodies (and frequently the clothes on them) apart, so that the naked lower half of a man could be seen dangling from a tree while his dismembered arms and torso were strewn elsewhere on the battlefield. Even this did not seem as horrible to me as the picture given of the victims of gassing, who sat upright in their holes, their faces turned blue. The poison gas used in World War I seems to be the one development in modern warfare that even military people found to be so universally horrifying that concerted efforts have been made to curtail its use in ensuing conflicts, my impression is successfully. Even reading about it one is instinctively repulsed by the idea of it more than all the other awful things going on, none of which I am going to pretend I would have been equal to standing up to at any age, let alone as an eighteen or nineteen year old. The only reasons I can come with for this repulsion are absurd, but I think part of it is the sense that poison is not really fair, that it is not even a test of military prowess. Also it seems to eviscerate the body from the inside out, especially the lungs, the pain of which seems to be more disturbing to contemplate than suffering even fatal battle-wounds.

The edition of the book I have. I got it for free in an incredible haul a few years ago when one of the local high school libraries had a massive book purge of books high school students have no interest in anymore, presumably to make more room for more multimedia/computer space.

The other reading list that I have been working through for the last twenty years, taken from the GRE literature test prep book, is overwhelmingly concentrated, to a surprising extent to my mind, on English language works, with continental European works very sparsely represented. This is one of the main reasons I came back to the IWE list, as it does have more of a presence of the non-English European literatures, especially novels, though this has not shown up in my reports thus far, the "As" being more heavily weighted towards English and American books than most of the rest of the letters. I have hardly read anything from the German countries especially since I was in school, and I wanted to correct that. I don't know that All Quiet on the Western Front is considered to be a great example of German literature, but some of the scenes at least, especially those that are away from the front or even reminiscences on the world away from the front, give one something of an atmosphere that is different from the standard scenes of the English and American literary worlds, that gives a flavor of the landscape and tone of life in Germany and old Europe generally that makes for some enjoyment in the reading, even though these are not described for the most part with a nostalgic aspect, and of course the abomination of the war is exposing the emptiness of much of the rituals of society and traditional life and rendering them obsolete. Still, for those of us who live such mental life as we have through the templates given us by the classic literature and art of the past, what else do we have?

In a strange coincidence, this is the second author in a row in this record with a personal connection to one of Charlie Chaplin's wives. Remarque was married to the at one time extremely gorgeous movie actress Paulette Goddard, who had previously been married to Chaplin (and Burgess Meredith as well) from 1958 until his death in 1970. Remarque, all of whose books sold well, though other than All Quiet none of them seem to be well remembered today, had evidently amassed quite a lot of wealth, as well as a serious art collection, by the time of this marriage, much of which his widow (who was his second wife) inherited upon his death, in addition to her own evidently already substantial wealth.

The Challenge

1. Jon Krakauer--Into Thin Air..........................................................2,266

2. Dennis McNally--A Long, Strange Trip..............................................65

3. New Webster's American Handy College Dictionary (4th Edition)...52

4. Vittorio Arrigoni--Gaza Stay Human....................................................8

5. Paul Dowswell--Eleven Eleven.............................................................1

Michael Marshall--Gallant Creoles.......................................................1

The extensive Zero list for this challenge includes War Classics: The Remarkable Life of Scottish Scholar Christina Keith on the Western Front, R.E. Foster, Wellington & Waterloo, Mike Brooke, Follow Me Through, Schmoop Literature's Guide to All Quiet on the Western Front, and Gaston Maspero's History of Egypt, Volume I. Maspero, a Frenchman, was actually an Egypt scholar of some renown. There are twelve volumes in the History all told, but like the Cambridge History of English Literature, the different volumes are often sold separately and it seems can be profitably read as stand alone books. I was considering taking it up if I could have procured a copy easily. I have actually read the Krakauer book before. It had some interest for me in a journalistic, zeitgeisty kind of way, but it is not something anyone needs to read twice.

Remarque

The movie challenge produced a pair of old classics, including the most famous one based on this post's book. I have seen both of these landmark films recently enough that I will probably pass on them for now:

1. On the Waterfront...................................315

2. All Quiet on the Western Front (1930)...229

I am curious to see All Quiet again and see how it compares with the book, though the film, and maybe the book too, are unusual in that they are more about the war as a whole than in the specific incidents and characters that it is made up of.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)