I knew almost nothing about this play going into the reading. It seems to have been relegated to the national literary attic for most of the past forty years or so, probably until people can figure out how to pull it out and handle it safely. It is about racial division, and really is a pretty daring and pretty strong take on the subject for the mainstream theater in 1924. O'Neill obviously was a white male, and perhaps no one is interested anymore in what he would have had to say about the American racial situation, but I am interested in it, especially since it is a significant departure from the way most other white guy American writers of the time (i.e. Booth Tarkington, F Scott Fitzgerald, even T S Eliot) seemed to regard it. O'Neill was immersed pretty seriously in the cultural and artistic life of this period, and he must have felt that the race issue impacted him in some way and that he had something to say about it. <I only wish I were so impacted and engaged in life>.

The 1960s introduction to the play in the IWE is truly a missive from a foreign country. Fifty years on, it defies contemporary intellectual propriety in about every way, though its intentions are clearly good and liberal in the context of its own time. I will reproduce it in its entirety:

This is a penetrating study of a controversial subject. A white girl, Ella, marries a Negro man, Jim, and she loses her mental balance. It is a foreseeable consequence in psychology and is not subject to controversy. On the message of the play, however, the United States divides on sectional lines. Generations of Northern students have been taught that the play is a protest against our culture, in its implanting of ineradicable prejudices. Southerners rather see in it a warning against the natural perils of miscegenation; and of course the warning is there, protest or no. The title is from a Negro spiritual.

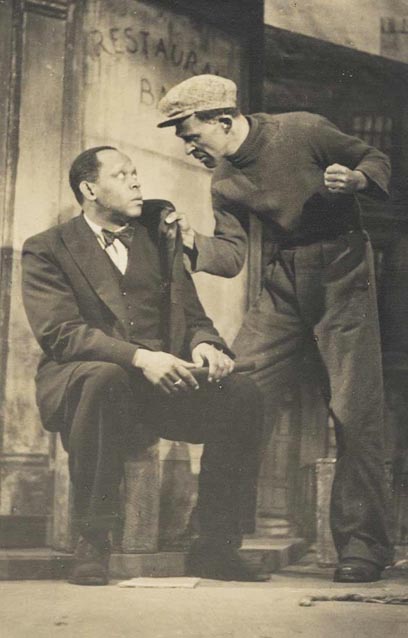

The famous actor Paul Robeson was the original Jim on the stage.

I am a northern student (as was O'Neill himself, at one time), so I suppose it is natural that I am inclined to assume that the first interpretation is closer to the intention of the author than that it is a warning against miscegenation.

The sets and stage directions in this, particularly in the first act, have a bold, modernist character about them that strikes one. The first three scenes of the first act are set on 'a corner in lower New York' where two streets converge, with intervals of some years between them. Tenements stretch away down each of the streets, one of which is populated exclusively by white people, the other exclusively by black people. Popular songs of the various eras depicted are heard--different ones on each of the streets--and as the years progess the streets are emptier and the noises 'more rhythmically mechanical, electricity having taken the place of horse and steam'. The fourth scene, in some ways the central and most jolting one in the play, takes place 'in front of an old brick church...people--men, women, children--pour from the two tenements (on each side of the yard), whites from the tenement to the left, blacks from the one to the right. They hurry to form into two racial lines on each side of the gate, rigid and unyielding, staring across at each other with bitter hostile eyes'. In truth I admit that if somebody--whether an angry female (whether of color or not), a pouty, sarcastic gay, or maybe even a straight white guy who suspiciously managed to stay in everyone's good graces--were to write something like this into a contemporary play, I might not trust the accuracy of the vision or find the same level of attraction to it that I have done here. Age also has a way of clarifying what in at attitude or vision is solid or deep and what wasn't that I have a hard time delineating in the present.

From a British production.

I also can't repeat enough how much I love the American language and literary consciousness of the 1920s and 30s. Every time I come back to this period it really hits me. Unfortunately I am very much in many of my habits and worldviews stuck in this period and cannot relate very well to people who are alive now and the things they care about.

The second act, with its scenes in the apartment, struck me as very reminiscent, in its mood, setting, and sense of frustrated male hopelessness, of A Raisin in the Sun. In a broad sense, of course.

Oona (1925-1991), Eugene O'Neill's extremely attractive daughter, who at age eighteen married Charlie Chaplin, who was fifty-four at the time, and went on to have eight children with him. The playwright did not approve of the marriage, after which his relationship with his daughter was severed.

The Challenge

1. Sam Harris--Waking Up......................................550

2. Daniel E. Dennett--Consciousness Explained.....144

3. Dan Smith--The Child Thief................................110

4. Julie Cross--Whatever Life Throws at You............71

5. Eva Stachniak--Empress of the Night....................68

6. Ezra Pound--Cantos...............................................39

7. Leann Harris--Second Chance Ranch......................8

The winner this time is subtitled A Guide to Spirituality Without Religion, which is something I might read, though the concept is not one that obsesses me. However, my local library does not have a copy of it, and I am not inclined to seek it out. There were some promising contestants this time, though. The Dennett book I think is supposed to be for an intelligence level above the general level, and the Ezra Pound, though finishing weakly in 6th place, was the result of a small alteration I have made in the process to try to get more serious books into the contest. I am betting the next Challenge gives us something we can actually read.

Paul Robeson sings the title song. It's a very good song. Obviously no one needs my pronouncement on the matter, but as a person who I am sure most knowing people would agree has and knows nothing of soul or anything in that way, the fact that I still like the song might be of interest to people who are in the same boat.

O'Neill referenced a number of old songs, some of which I was familiar with, some of which I was not (but all of which I want and think I should be) into the stage directions. There was "Only a Bird in a Gilded Cage":

"Little Annie Rooney", here in one of the better efforts of the Lennon Sisters:

"I Wish I Had a Girl"

"When I Lost You"

"Waiting For the Robert E Lee"

"Frankie and Johnny"

"Annie Laurie"

"Old Black Joe"

Merry Christmas.